FOOTNOTES

1Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

2 Maiko Jinushi: http://maikojinushi.com/

3 Akira Takaishi:http://www.akiratakaishi.com/

4 Nicolás Pellizer: @_duiyo

5 Syafiatudina: https://dinamakan.online/about

6 Wok the rock: www.goethe.de/prj/nus/en/ats/wtr.html

7 Kunci: www.kunci.or.id/about-us

8Art Center Ongoing: https://www.ongoing.jp/

9 Kenji Ide: @works_kenjiide

10 Boat Zhang: http://www.boatzhang.com/

11Hinamatsuri, Hinamatsuri, also known as Doll’s Day or Girls’ Day, is an annual festival in Japan held to celebrate the health and happiness of female children and femininity in general.

12Tanabata or Star Festival is a holiday derived from the Chinese Qi xi tradition “The Night of Sevens.” It is tradition to write Tanabata wishes on strips of colored paper and hang them on trees made of bamboo branches. According to tradition, this is the only day of the year when the two stars, Altair and Vega (representing two lovers) can meet.

13Sara Gassmann: https://www.saragassmann.ch/

14 Ryuichiro Otake: @ryuichirootake_studio

15 Fumiaki Akahane: http://www.fumiakiakahane.com/

16 Gyoji Nomiyama: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14108946

17 Morikazu Kumagai:http://kumagai-morikazu.jp/

18 Kenjiro Okazaki: https://kenjirookazaki.com/eng/

19 Masaya Chiba: https://shugoarts.com/en/artist/143/

20 Super Open Studio: https://www.superopenstudio.net/

21 Daichi Takagi: https://daichitakagi.net/

22 Meriem Bennani: http://meriembennani.com/

23Noboru Takayama (1944-2023). See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/subterraneans-and-mirrorless-mirror/

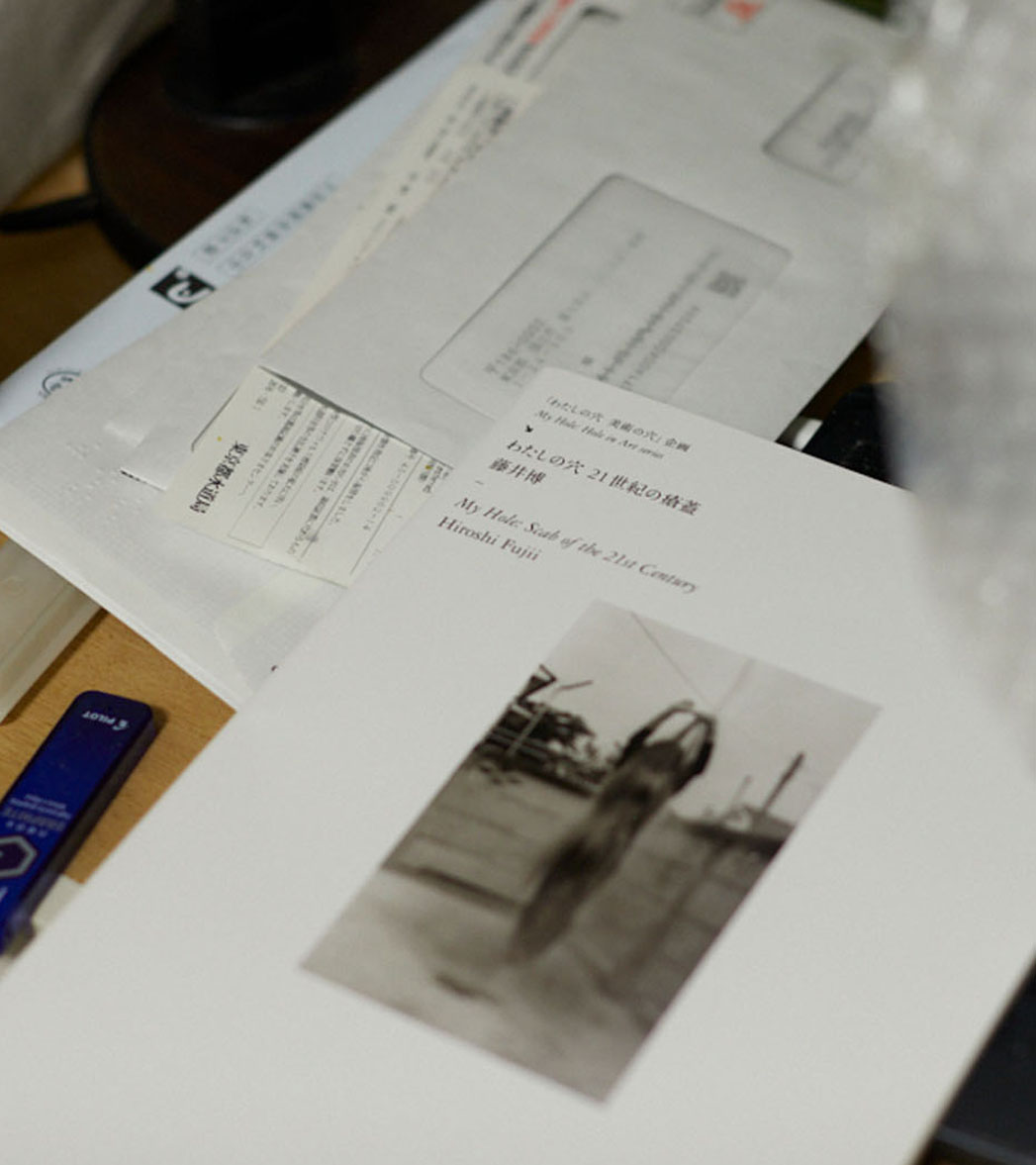

24In 2018, Akira Takaishi and Tomohito Ishii curated an exhibition called My Hole: Scab of the 21st Century at Space 23℃, a small art space, set up in the garden of artist Koji Enokura’s widow’s house, in the residential area of Todoroki. Four works by Fujii (1942–) made between the 1970s and the 1990s were shown there.Regarded as a forgotten Mono-ha artist, a writer who developed his activity in the same period as the Mono-ha artists, he was not properly historicized within the Japanese art world.In the curatorial text for the exhibition, Akira wrote: “The practice was more critical than the writers of the same era, and it cut through the outline of the body of art. Fujii’s work is not the core hardcore of Japanese contemporary art, but the hard film formed at the boundary between the inside and the outside, the core crust core of the scab”. See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/my-hole-scab-of-the-21st-century/

25Mono-ha (も の 派) is the name given to an art movement that has its origins in the mid-1960s in Tokyo. It is generally translated as “School of Things”, a term coined with disdain by critics in Bijutsu Techo magazine, long after he began exhibiting his work. The Mono-ha artists did not start out as an organized collective. They investigated materials and their properties in reaction to ruthless development and industrialization in Japan. They explored the encounter between natural and industrial materials, such as stone, steel plates, glass, light bulbs, cotton, sponge, paper, wood, wire, rope, leather, oil and water, ordering them mostly unchanged. They share characteristics of the Land Art movement, Fluxus and Conceptual Art. One of the most recognized artists is Korean Lee Ufan (1936), a decade older than the rest, who settled in Japan at the age of 20. Some artists are: Nobuo Sekine (1942–2019), Katsuro Yoshida (1943–1999), Susumu Koshimizu (1944–), Koji Enokura (1942–1995), Kishio Suga (1944–), Noboru Takayama (1944–) and Katsuhiko Narita (1944–), Jiro Takamatsu (1936–1998), Shingo Honda (1944–2019).

26https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/shigeo-anzai-24656

27 Clemence Renaud: https://www.clemencerenaud.net/ and the video here: https://www.clemencerenaud.net/gloires-et-declins

28 Koji Enokura: https://www.takaishiigallery.com/en/archives/17458/

29 In 2015, five artists born in the early 1980s, Akira Takaishi, Maiko Jinushi, Tomohito Ishii, Tomohiro Masuda, and Saeka Enokura, held the My Hole, Holes in Art exhibition in a house. Makiko Hara writes: “In re-examining the meaning behind the 'holes' in Haruki Murakami's writings illustrating the turning point of post-war Japan in the 1970s, and the meanings of the 'holes' that many artists were digging at the time, those artists featured here aimed to survey their own 'holes' in 2010s reality.”". See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/my-hole-hole-in-art/

30 Following the series of exhibitions related to Mono-ha artists that we listed before, I find three exhibitions that occur simultaneously in 2019: Hole: Hole in Art Series. On one hand, we have Indeterminate area with works by Koji Enokura (1942–1995), Noboru Takayama (1944–) and Hiroshi Fujii (1942–) in Space 23ºC, then the solo show Pleasure Plane by Tomohito Ishii in Capsule, and finally Akira Takaishi’s shows Descent Garden at Clinic. Let’s remember that Ishii and Takaishi also participated in the group exhibition My Hole, Holes in Art (2015) and had already curated together the exhibition My Hole: Scab of the 21st Century by Hiroshi Fujii (2018). See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/my-hole-hole-in-art-series-2019/

31Hagiwara Projects (www.hagiwaraprojects.com) is a gallery located in the Kōtō ward, Tokyo. It represents artists Miho Dohi, Yuta Hayakawa, Shunsuke Imai, Tomotsu Kido, Ryota Nojima, Nobuhiko Nukata, Zak Prekop, and Maiko Jinushi. I visited the space during the opening of the Onsen Confidential group show, organized with the Crevecœur gallery from Paris, and had a few words with its friendly director Yukari Hagiwara.

32 Yamantaka Eye: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamantaka_Eye

“If I had money, I would buy works by my artist friends. Our friends are amazing artists.”

Maiko Jinushi and Akira Takaishi

I arrive at Kunitachi train station one hour before the interview. I sit at Komeda coffee shop, right across the street, because I love the man on the logo and the curls of smoke coming out of his cup of coffee. I order a coffee with milk, and it comes with a bread roll with an almost transparent apple jam. I’ve been in Japan for two weeks now, and it’s the first time I get an oshibori, a warm rolled towel to clean my hands when I sit at a table. I thought that COVID-19 had eradicated them, but the entire cafeteria, with the green velvet couches, seems to live in the past.

A few minutes before the interview I met Marisa Shimamoto1, the project’s photographer, at the station’s south exit and we drove to the apartment where the artists Maiko Jinushi (1984)2, Akira Takaishi (1985)3, and their daughter Sara live.

Kunitachi is a city located about forty minutes from downtown Tokyo. The artists live in a large five-floor building complex, separated by wooded corridors, with parking spaces for bicycles at the entrance of each module. We’re running ten minutes late, so I let Maiko know that we’re already at the front door.

“We’re going down!” she replies in the chat.

We all meet halfway on the stairs. The three of them come out to receive us, Maiko, Akira and Sara in Akira’s arms. I suspect it’s a Japanese tradition to greet guests at the door. This is the third interview we do for Artists’ Collections, so I already have some practice taking off my shoes in the houses’ genkan. If they offer me slippers I always accept.

They are as warm and loving as I imagined. We talk in English, and although this is an interview, I feel like I’m visiting some friends at home.

D. “How old is the building?”

M. “I think more than fifty years.”

D. “It doesn’t look like it!”

M. “Inside is fine, but outside…”

A. “They recently painted the exterior.”

D. “Is it bigger than other apartments?”

M. “Actually, there is more space between buildings. Normally in Tokyo you can see your neighbor very, very close.”

D. “I understand, I guess you can hear everything. This building complex also has plenty of green spaces for children to play. Sara, you’re going to go play with the neighbors,” I say in English to the baby, who clearly doesn’t understand, but we laugh anyway.

D. “The doors are a bit low, aren’t they? Akira is almost touching the lintel.”

A. “Yes, they are custom made for Japan,” he says laughing.

MS. “Buildings around this time are usually this height, in the new constructions they are higher.”

M. “We had to move very quickly, because there was a fire in the place where we lived before. So it’s still a bit messy here. Many things still have a little soot on them. But it was a good opportunity to review everything we had.”

A. “Including the art collection.”

Like a mantra, I repeat during the interviews the same action: I give them the Artists’ Collections book, the sweets that I bring as a gift and an art piece “made in Argentina”, specially chosen for each one. It is a small work/print/poster to add to their collections.

This couple is very special, so I asked my friend Nico Pellizzer4 to make a watercolor of some corner of their house that had caught his attention. A few months before traveling to Japan, I showed Nico the photos that Maiko emailed me with various works. On the seal of a triangular-shaped window were little plants and some curious objects, including some broken ceramic pieces, a gift from a friend after her trip to Mexico. In her email, Maiko added this debris to their collection list: I love the object and its memory, so in some way I consider it art— she wrote.

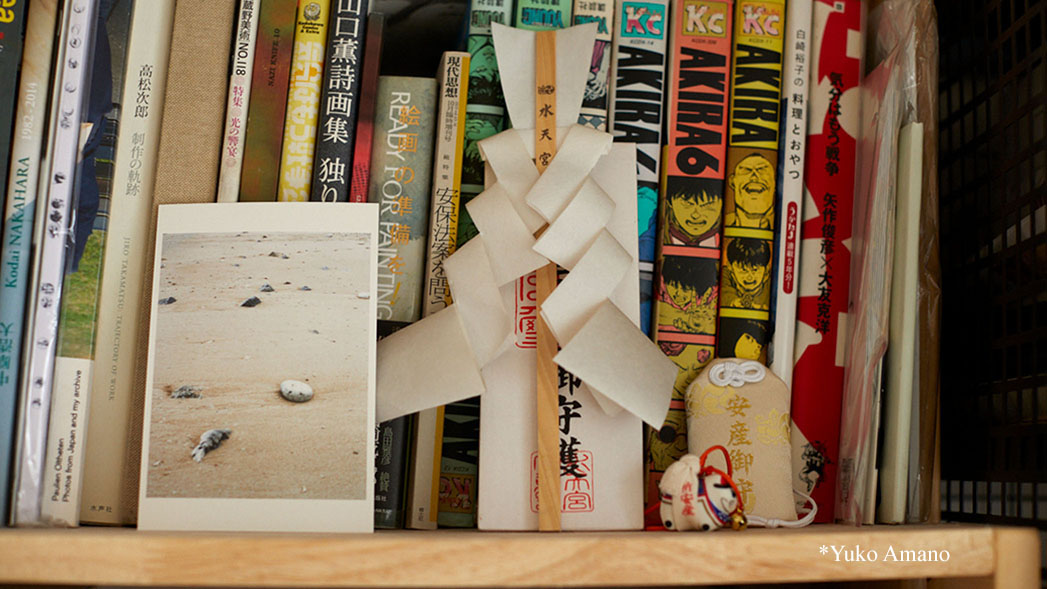

One of the first questions I ask, then, is, “Where is the debris?” and they lead us directly to a room-office. The broken pieces now rest on a shelf of the bookcase and some things are slightly out of place compared to the photo from a year ago. But the spirit remains the same. I give them the watercolor; they are surprised, and they love it. While we talk, Akira starts to rebuild the scene as it is painted, taking the task seriously, adjusting things here and there with Japanese precision.

D. “Now that we are here, I would like to know the history of the debris.”

M. “These pieces were a gift from my friend Syafiatudina,5 who lives in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. She is a curator and a very good friend of ours. Before coming to Tokyo, she was traveling and brought us this as a souvenir.”

A. “But there is another story, too. She is not just a curator—for you… she is a very special friend. They met in Yogyakarta.”

M. “Yes, yes, yes. Indonesia was the first place I traveled to as an artist. Talking about Yogya will be a long story. It was a very special experience for me… At first, I met Dina’s boyfriend, Wok the Rock6. He is an artist and came to Koganecho for a residency. We became good friends. Wok opened a bar as his artwork, and at the opening, I met Antariksa, a founder of KUNCI7 Cultural Studies Center. Antariksa told me about a Japanese painter who came to Indonesia during Japanese occupation. I had never heard about him, but Antariksa told me he had established the first modern-art school in Indonesia. It impressed me a lot. Until then, I did not really know about details of Japanese occupation in Indonesia. I felt shame about my ignorance. I wanted to know more about it, and also about Indonesia, so Antariksa invited me to KUNCI. Dina is a member of KUNCI, and, as I told, Wok’s girlfriend, so we spent a lot of time together during my stay. KUNCI is open for local people as a library, and Dina sometimes organized workshops/casual public discussions with artists, researchers, students, and locals. Her way of communication and perception of the world was… just super cool for me. Very intellectual, kind and funny. I had never known that kind of person, and I hoped to be like her, ha ha.

Communities in Yogya were also very impressive. Not only KUNCI; there were many collectives, and many of them connected each other. Since Yogya is a small city, they went around by motorbike, hung out every day and night, and talked about art and everyday life seamlessly.”

D. “When did you go?”

M. “This trip was at the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014. That experience changed my idea of how to see the world as an artist. Before going to Yogya, I looked only at Western art world and histories, even unconsciously. I realized that it was a limited concept, and that there were many things I didn’t know at all. After that, I started traveling more. Also, I noticed I was bound up with a concept of an artist being alone and original. People in Yogya didn’t care about it. They seemed to think sharing is much more important than having an original concept alone.”

A. “It’s not just about producing works of art, it’s something else too, it’s the way of living.”

M. “When I came back, I told our friend Nozomu Ogawa about Yogya. You went to Art Center Ongoing8 the other day, right? I wonder how you found it. Because when we emailed each other, I thought we could go together, I was going to suggest it.”

D. “Well, I visited because I had seen in your CV several things related to the place, and it seemed important to check it. I also saw that Kenji Ide9 had a lot of exhibitions there. When I visited last week, there was an exhibition by the artist Boat Zhang10. I chatted with Nozomu for a while, and he told me that he has had that space for fifteen years.”

M. “Oh sure. Quite a researcher, ha ha.”

D. “More like a stalker, ha ha. Since I’m an outsider, I want to know the spaces where you circulate, and get a little bit closer to the local scene.”

M. “At the beginning he showed young, unknown artists, but now the Ongoing community is already quite recognized. Over the years artists became well known.”

D. “I see. He also gave me the book he published about his journey through Southeast Asia”.

Southeast Asia Research Trip is a survey carried out by Nozomu Ogawa in 2016. He visited, in three months, eighty-three art spaces in nine countries of Southeast Asia. A tight schedule! In the book’s preface he explains it in a few words: “I myself run a small art space called Art Center Ongoing in Kichijōji, Tokyo, Japan. I heard a rumor that there are countless independent art spaces like mine, and decided to plan this trip.” It is a beautiful guide, with photos of those meetings, some little drawings in the margins, and precise and funny chronicles (in Japanese and English) that is a pleasure to read. In the Thailand section, there is an exhibition in Chiang Mai space of five Japanese artists curated by Ogawa, including Maiko Jinushi and Kenji Ide. Following the tone of the book, I’m glad I left things out of my suitcase to bring it home with me!

M. “Actually the first one to go to Indonesia was Kenji Ide, and he brought Wok the Rock to Japan, and we became friends. Then I went to Indonesia, and when I came back I told Nozomu about Indonesia… and so on.”

D. “I love to learn a little about your community, who your friends are, and how these ideas circulate. Let’s check what other works we have in this room. When I saw this piece in the photos that you sent me, it reminded me of Man Ray.”

M. “Ah yes, it’s the base of a very old iron. It belonged to my great-grandfather. When my family had to empty his house after he passed away, I saw it and found it interesting.”

A. “It wasn’t even an electric iron. And now it’s unusual, these things don’t exist anymore, but at the time it was an object of everyday use. Comes from a very different time.”

M. “He was a very good shoemaker in Fukushima, and he had a lot of tools too.”

She unwraps a hammer and a pricker, kept in a newspaper sheet.

D. “Do you use them? They look handmade, don’t they?”

M. “No, the truth is that I don’t use them. They look like they were made by him, I think.”

A. “I would be afraid of breaking them if I use them,” he adds laughing.

D. “They were made for a very specific use, I imagine.”

M. “I also have this handicraft that I bought at a Christmas fair in Germany. It’s like an amulet. It’s a toolbox.”

D. “Do you link it with your grandfather?”

M. “No, I don’t connect it with him, but with my career, I bought it as a charm for myself.”

A. “It must be a decoration for the Christmas tree.”

M. “These two dolls were made by Akira, they are traditional Japanese figures to pray for the health of girls,” Maiko adds while she points to two figurines.

D. “But there is a girl and a boy.”

A. “It is a very old-fashioned tradition (Hinamatsuri Festival),11 where people pray for the little girls to be married happily in the future. And it’s also to ask for the birth of future babies.”

M. “We discussed a lot if we had to do them because it’s a belief we obviously don’t agree with, and also because we have no interest in Sara doing it, nor do we think Sara identifies with it. Sara can be any of the two dolls. She can be either one that she wants to be.”

Japan is full of festivals and traditions that I discover with the stories that they tell me. I wonder if they have any real meaning today or if they are just empty rituals.

D. “How did you choose Sara’s name? It’s a western name, right?”

A. “Well, it’s not just western, Sara in Japanese is a type of fabric. It has some western and Jewish roots, but it is not totally foreign to Japanese culture. We also have many friends named Sara in different countries, and they are all good people, ha ha, without exception.”

M. “There is also a song for the celebration of July 7th, which is a festival of the stars (Tanabata Festival),12 and the song says: ‘The bamboo leaves rustle (sara sara),’ which is the sound that the leaves make when they move. Also, she was born in July.”

Sasa no ha sara-sara / Nokiba ni yureru / Ohoshi-sama kira-kira / Kingin sunago / Goshiki no tanzaku / watashi ga kaita / Ohoshi-sama kirakira / sora kara miteiru

The bamboo leaves rustle, / Shaking away in the leaves. / The stars twinkle / On the gold and silver grains of sand. / The five-color paper strips / I have already written. / The stars twinkle, / And there they will watch us.

A. “Sara is also the sound of a word, which has a different character, and is a type of sacred tree linked to Buddhism. Many reasons for her name.”

The four of us are still in the room-office, Marisa takes photos of the art works and of every corner, Maiko poses holding some pieces and Akira has Sara in his arms while we talk. It’s the end of summer, and I feel a sweat drop running down my body.

D. “We only have one object left from this sector, this snake-shaped ceramic.”

M. “It is a work by the artist Sara Gassmann13, from Switzerland. I met her at a residency in New York. When she had a show, I took some photos of the exhibition and she gave me this work as a gift.”

D. “One of the beloved Saras.”

A. “Yes, yes.”

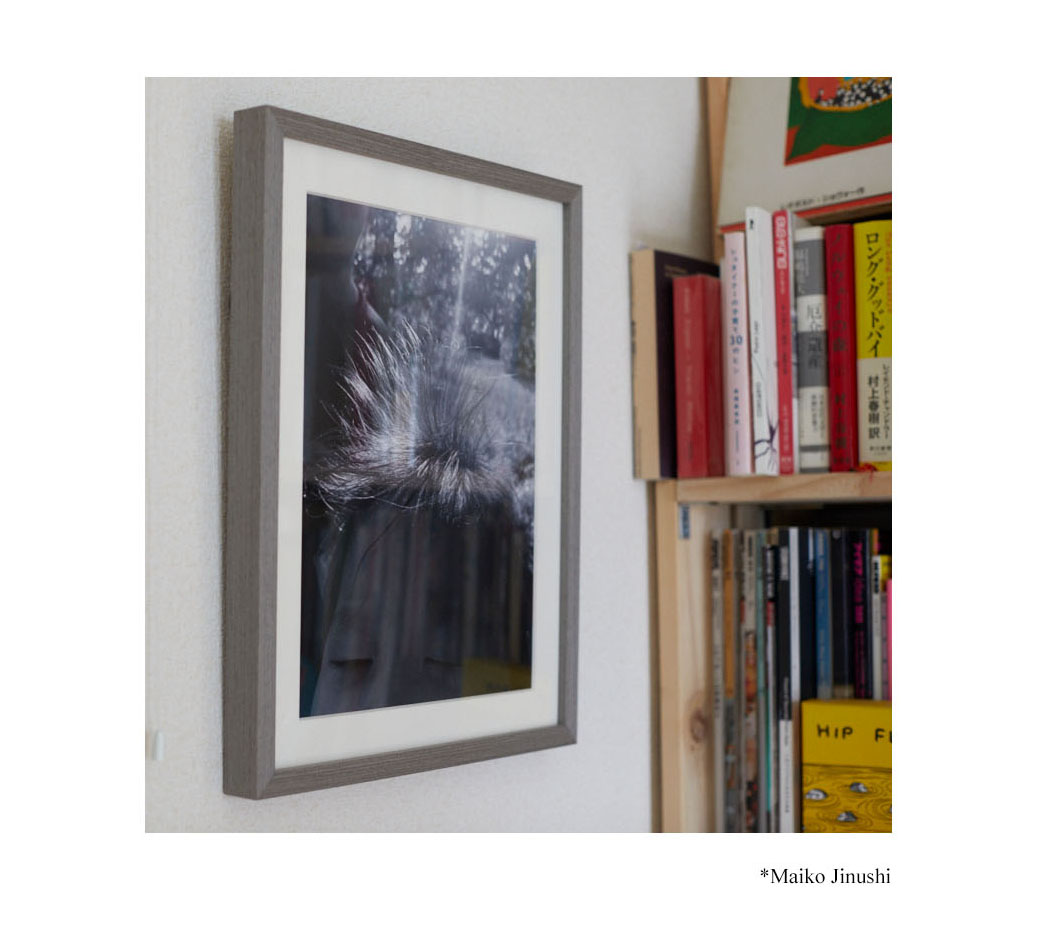

D. “Since we are here, we can start talking about this photo. It’s a boy, a girl, I don’t know. It’s someone’s head, ha ha.”

M. “It’s Sara’s head! I developed my newest work from this picture. Now I'm showing it in the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. Akira and I are participating in this exhibition as members of an art collective called Ongoing Collective. The collective members made an installation as a village-community of artists there.”

The art collective works in a place called Sansho House, in Niigata prefecture, about three hours by Shinkansen from Tokyo. It is a huge space, with very high ceilings, in which they share daily tasks. From raising the children to creating the works in a large sugoroku game-style installation, with boxes to move forward or backward. They do performances, weekend workshops, and film screenings, among other activities. At @ongoingvillage Instagram account I found some photos of Akira painting his work, locked in a small room made of transparent plastic walls (Breaking Bad style) and a video of Maiko touring the space with Sara on her back. Participants are: Morito Inoue, Kyoko Idetsu, Ayaka Ura, Ryo Ikeda, Hiroyuki Ohki, Itaru Ogawa, Maki Katayama, Yuya Koyama, Keisuke Sagiyama, Hikaru Suzuki, Yoshiki Tanaka, Kento Nito, Masashiro Wada, Yoko Abe, Nozomu Ogawa, and our friends Maiko and Akira, of course.

D. “Is there any other work in this room?”

A. “This is Maiko’s work, from her beginning years, it’s quite old. It’s a discman.”

D. “Oh, I didn’t realize,” I said while holding the painted object in my hands. “Well, I used it a lot as a teenager.”

M. “Yes, ha ha, it’s a lost culture.”

A. “This is from Ryuichiro Otake14. He is a friend of both of ours. I did a group show with him. And he forgot it, so I just took it. I found it in my bag,” he says, joking.

D. “That’s a very common story in artists’ collections.”

The five of us move now to the living room. We sit down to look at the Artists´Collections book so they can have a pause. I am surprised by the dedication they show when looking at it, and the time they take to do it. Maiko watches the entire book, page by page. I tell them some stories about the collections of Argentina that I think they may enjoy.

In the living room, which is separated from the kitchen by a playpen made for Sara, there are some works hanging on the walls and many toys on the floor. I get ready the list of works I brought with some information.

M. “Ah, you were investigating them!

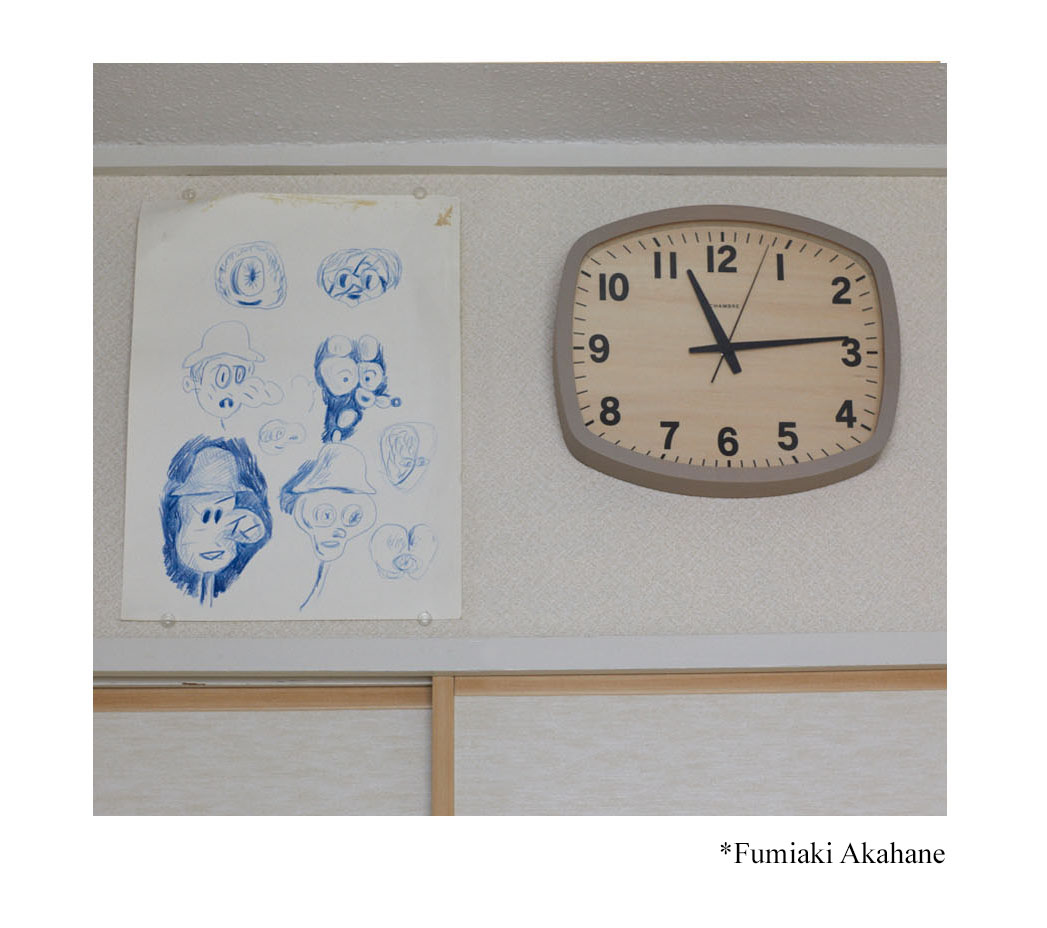

A. “Fumiyaki Akahane15 is a friend from university and a talented painter. I love his drawings,” Akira starts as he unwraps a scroll paper with a drawing by the same artist that hangs next to the clock. “The story is that I took some drawings from his studio,” he says laughing. “He had a lot of drawings and he was getting rid of some, so I rescued them and took them with me.”

D. “Are they from your student time?”

A. “No, they are from a recent visit. When we were students I loved his work, what he did seemed very powerful to me. I still wonder how he did that kind of work as a student. I still like the ones from that moment.”

D. “From what I saw online, his work now is very different from this one, he is working now with many textures.”

A. “Yes, I like both stages.”

I can’t help but be obsessed with the big clock that hangs next to the works. Clocks are always present in Japanese houses, and they have a unique shape. It’s rectangular and oval at the same time. I love the ones in train stations too, with green numbers.”

D. “I need to buy one of these Japanese clocks. They remind me of the train station ones.”

M. “It’s different, but I understand what you’re saying, we bought it at Unico.”

A. “It’s quite expensive, around 12,000 yen (90 dollars). We loved it.”

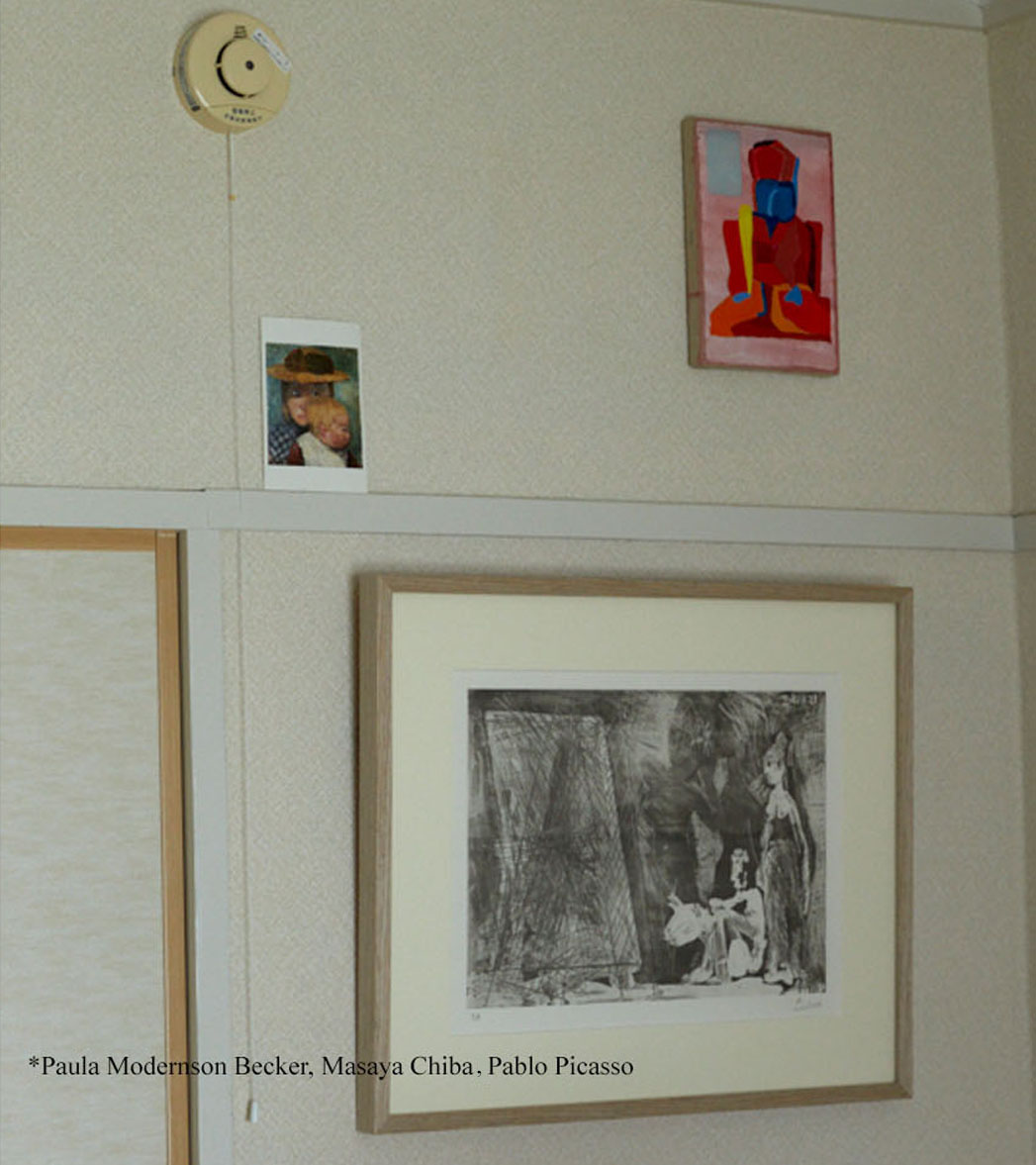

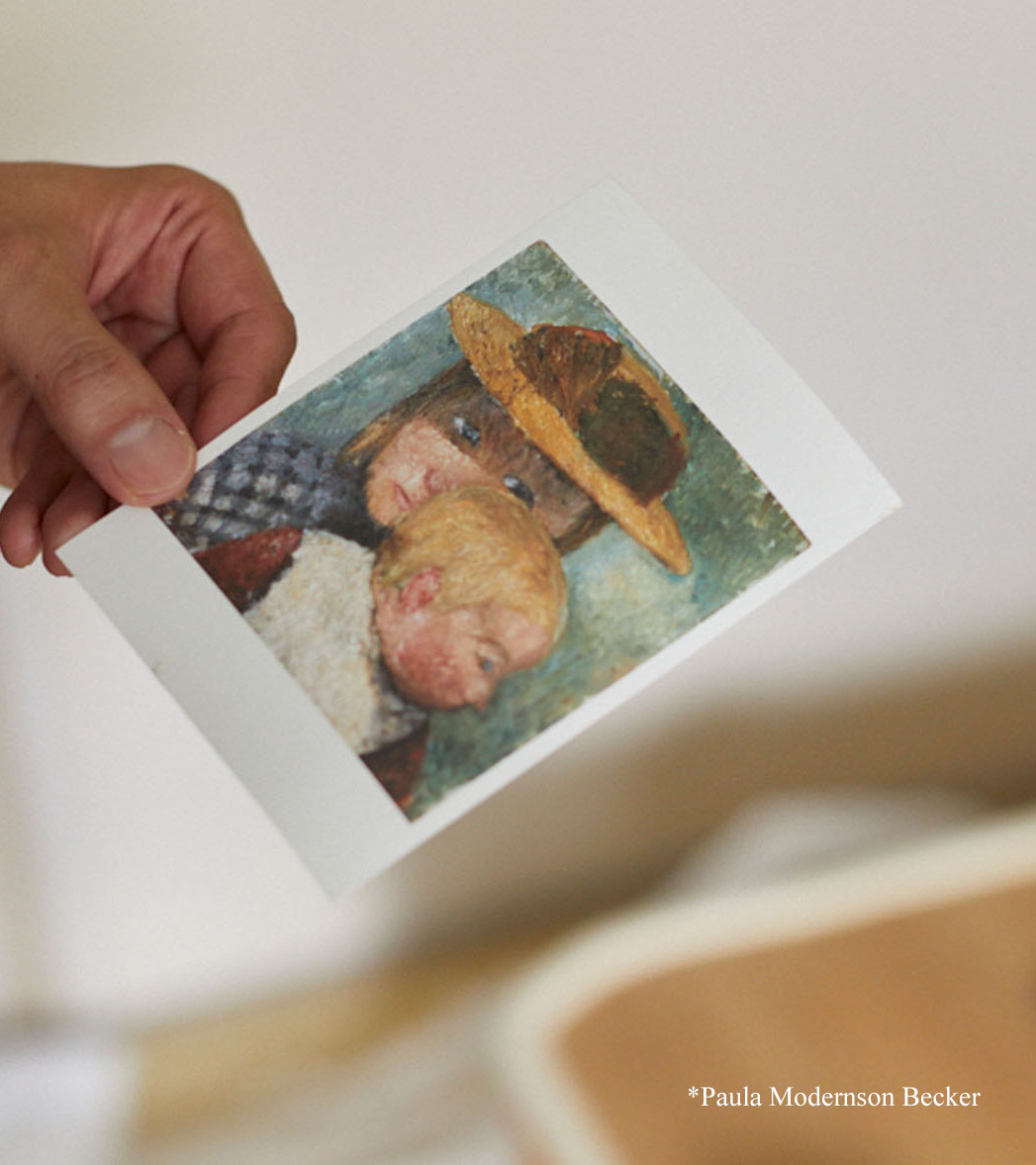

D. “Tell me about the postcard next to it.”

A. “She is a German artist; her name is Paula Modernson Becker (1876–1907).”

D. “I don’t have her on the list.”

M. “Well, it’s a postcard, ha ha, but we love her. She was a pioneer.”

A. “We bought it at a retrospective that was held in Japan. She is a female painter, doing these works in 1903. She was little known at her time in which Matisse and Picasso were super famous. And she should be treated like one of them. Speaking of celebrities, here we have our Picasso,” they say while pointing to another of the works on the same wall.

D. “It belongs to your mom, Akira, right? So, you told me there are three works from your mother’s collection “on loan” in this house… Is she a collector?”

A. “Not at all, but she bought some works at online auctions. Fifteen years ago, auction sales in Japan were not so popular, there were not as many as now, when everyone is looking to buy works online. The seller had no idea what it was, or where it came from. So she found it by chance and we believe it is an original Picasso print. It’s possible,” he concludes laughing.

M. “In fact, his mother found good pieces, she has a very good eye.”

D. “What does your mom do?”

A:. “She is a housewife, now she is retired.”

D. “I’d like to see Gyoji Nomiyama’s painting (1920–)16". I pronounce the artist’s name written down on my list with difficulty.

M. “We’re sure it’s a real one. It had an original frame and when we changed it, we saw the signature on the back. He is quite famous in Japan’s art history, and a good painter and essayist, his texts are very interesting.”

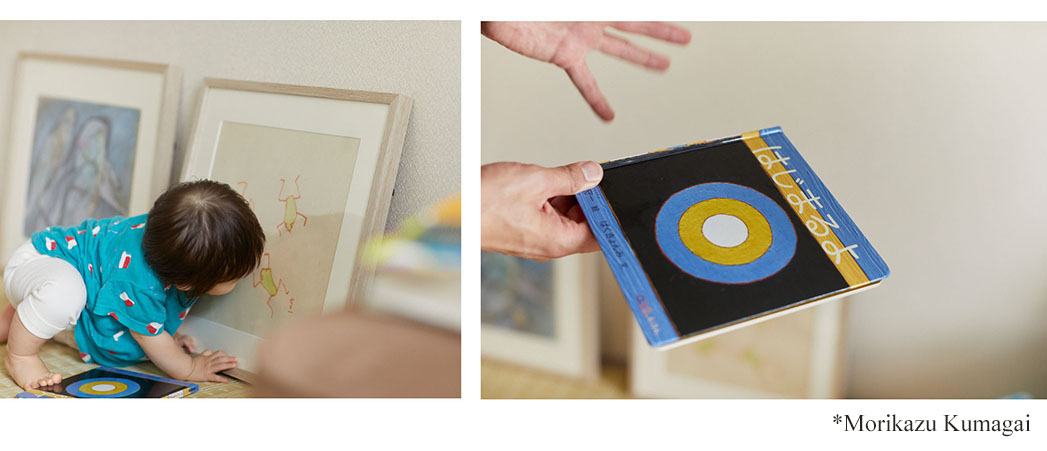

D. “It is the kind of work my mother would like too,” I joke. “And then the third work is from Morikazu Kumagai (1880–1977)17. He seems like an incredible person to me, he was also born in the 19th century.”

A. “He is very important to Japanese art.”

M. “I think his mom saw the title Frogs Painting and she recognized the artist, so she bought it. The one who sold it didn’t know, I think.”

A. “There’s this children’s book with his work,” says Akira as he brings some extra material to show me.

D. “He has his own museum in Tokyo, have you visited it?”

A. “Yeah, sure.”

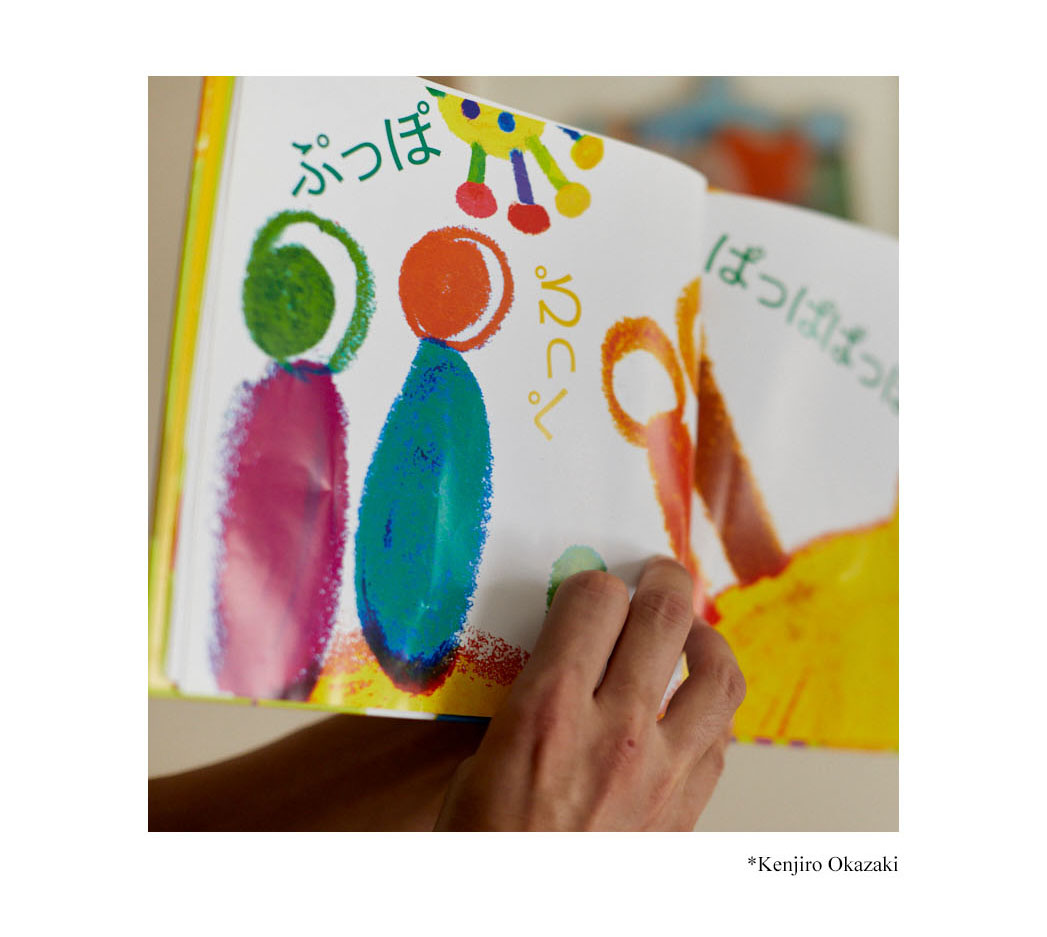

Akira brings more books from artist Kenjiro Okazaki (1955–)18.

M. “He must be almost 70 years old.”

A. “He is a genius, he is a theoretician. I’ve been his fan since I was a teenager. I bought this work when I was a student, I admired him a lot. At that time, he was not considered so much as an artist, but more as a critic. I saw a small exhibition in a gallery and I bought it. It was my first purchase, I was about 20, 21 years old. I paid 20,000 yen (150 dollars) or so for it.”

D. “Not much, like the cost of two clocks.”

A. “His work is more serious, that’s the reason why it was cheap, this is more like a sketch, a minor work, that he did for fun,” he explains to me while he holds and moves the piece so I can see how a face takes shape on it. “Do you see it? Here is a nose...”

D. “It’s a painted corrugated cardboard, very simple. May I see the back?” The knotted cloth cord used in Japan to hang the pictures catches my attention. “We use a simple metal wire in my country,” I say while I show them some examples in the Artists’ Collections book.

M. “Ah, cord is a very traditional Japanese thing.”

A. “As an art installer I can tell you that wire is better.”

M. “We also have the children’s book of Kenjiro, and Sara loves it.”

MS. “Ah, my children have it too, but I didn’t know about this artist. They love it, it’s about sounds.”

Akira plays them for me: “papapopapa pu popepi,” and other funny sounds.

M. “Onomatopoeia…”

D. “Akira always brings great context information, books and extra material, it helps me a lot. The investigator,” I say, and we laugh.

M. “He ‘investigated’ you too before you came,” she tells me with a funny and complicit voice.

D. “Me? But I’m not famous, ha ha.”

M. “On Instagram.”

D. “Ah yes, there is a lot of material there, ha ha.”

Until this visit, I hadn’t had any email exchange with Akira, and beyond following each other on Instagram, I didn’t know anything about his personality. To my surprise he turned out to be a passionate and caring person. His laugh is present during all the interview audios. I already adored Maiko since her first email response a year ago, when she wrote: If you would like to know a person who has more (and proper) collections, I think I can introduce them, so let me know. Hope you can get the opportunity to come to Japan. If it happens, please come to our place too 😊. I can’t think of a better destination than this house for Artists’ Collections.

M. “We prepared the house yesterday for your arrival, we cleaned up everything. We made sure everything was fine.”

D. “In Japan there is an obsession with cleanliness. Every morning when I go out I see people cleaning on the street, in the subway, in the shops, in the parks, and also sweeping the leaves outdoors.”

M. “Our house is usually messy, ha ha.”

Sara keeps repeating words… “papapapapa.” Akira brings more books. Some small colorful paintings of Masaya Chiba19 appear. They have one hanging on the wall but they bring two more so I can see them.

M. “These are like sketches, he ‘stole’ them too,” she says, looking at Akira and smiling.

A. “I didn’t steal them, ha ha, he was moving, there were a lot of things, it was very difficult to sort them out, it seemed that an earthquake had happened, or that a car had passed by.”

D. “So, you did him a favor.”

A. “It was very difficult to tidy that room up, I was very tired at the end. At that time, he was going to Toronto and he had to move everything to his mother’s house, and the house was full of stuff and he couldn’t take everything with him, so I took them… and he said, ‘Yes, come on, please!’”

D. “When was this?”

A. “Eight years ago or so…”

D. “He wasn’t as well-known as he is now.”

M. “Mm, he was already well known.”

D. “I really like his work. Do you know him, Mari-san?”

MS. “No, I don’t know him.”

M. “How do you know him?” she asked me, very intrigued.

D. “Well, when I was researching Japanese artists for this project I came across him and I loved his work. I checked his work for a while, I found his exhibition at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, and found it quite impressive. And I thought, ‘This is the kind of artist I would like to interview.’”

M. “Oh really? In fact, we thought Masaya might be someone to introduce you to.”

A. “He has his collection; he bought my work too.”

D. “I sent him a message at the time, but he never answered back. Then I found you and I loved the idea too, but he was one of the first Japanese artists I saw and whose work I connected with.”

M. “How incredible that coincidence. We thought of him when you wrote to us, but he is always very busy.”

D. “Yes, that’s what I imagined. He also has a project with Kenji, they do some Open Studios20, right?”

A. “They are best friends.”

M. “Yes, they are close friends. I hesitated whether I would introduce you to Masaya or to Kenji, because they both collect works. And in the end it was Kenji.”

D. “I love it, we are going to interview him at his house the day after tomorrow.”

At the entrance hall, next to the living room, there is a work by Daichi Takagi21.

A. “He’s a friend of Maiko’s from Tama Art University, this was a wedding gift. It’s called Still life.”

D. “I love this very simple work of a falling rain that I saw online,” I add while I show him my notes with some works that I found by the artist.

A. “Yes, this is a later piece, after his trip to Amsterdam.”

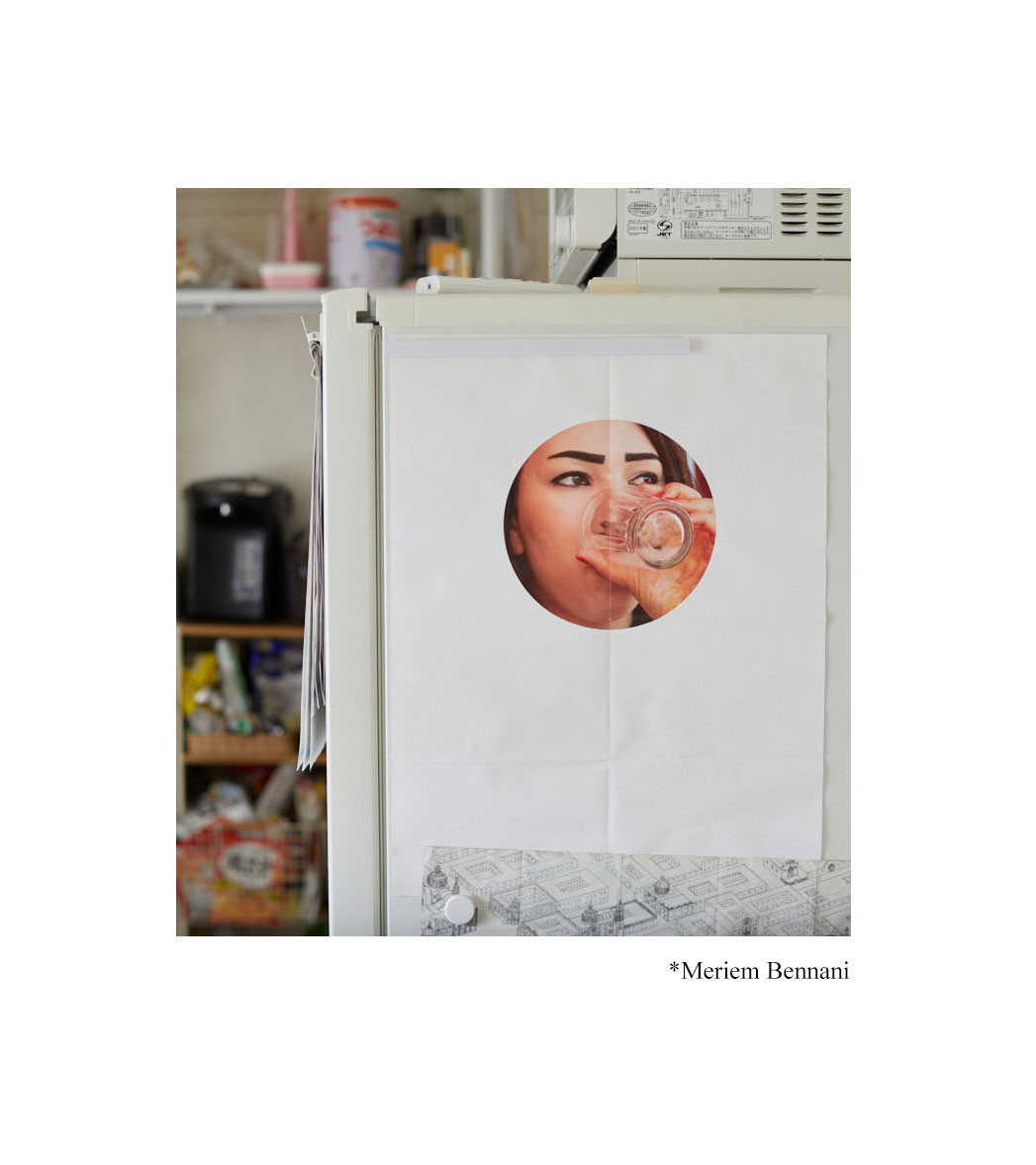

M. “Let’s not forget to talk about this poster, it wasn’t on the list, but I want to talk about it. It is a piece by Meriem Bennani22. She is a video artist. It is the poster of her exhibition in New York, in an alternative place, of experimental art. When we were there in 2017 we saw her exhibition, quite incredible. And after that she became very popular. She lives in New York, but she is from Morocco.”

While we talk, they both take thousands of magnets from the fridge to spread out the poster so that we can see it.

A. “She is now very famous, almost a celebrity. At that time, she was not so well known.”

D. “How did you get the poster?”

M. “It was the poster of the show, you could take it with you. We didn’t ‘steal’ it,” Maiko jokes.

D. “There are many similar stories in my book about someone ‘keeping’ the work of another colleague.”

M. “The same thing happens everywhere.”

We move to the last room of the house, Akira’s studio. His work hangs there, with acid, vibrant colors.

A. “I’m thinking of moving to a bigger studio, because the materials I use can be toxic, and I need more space, this is more of an office at the moment.”

We move like in a dance choreography, so Marisa can take the photos. “I move over,” “Pose here,” “Shall we sit on the floor, or do you want to take it to the other room?” “Let’s stay here to change the background” are some phrases I hear when I type up this interview from audio recordings.

D. “The pile of flat boxes caught my attention. I love these little boxes, they seem unique to me.”

MS. “Really?”

I guess in Japan putting a painting inside a box, almost “tailor-made” for it, seems to be perfectly natural. They are “kings of packaging” after all. If a small cheese has its individual wrapper inside a package with other tiny partners, why wouldn’t a work of art have its own specific box?

Akira unpacks things while kneeling on the floor.

A. “This is not on the list,” she says, unpacking a small wooden object.

D. “Let me write down his name, Takayama, Noboru23 (1944–2023).” I write his name in my notebook in the way artists are named in Japan. First comes the last name, then first name. In order to make it easier for readers (on this side of the world), I’ll use the reverse mode in these interviews.

A. “This piece is related to a curatorship I did in January of this year (2022). I did a show with him, but it was still pandemic time, and he couldn’t come, so he asked me to build up the work and he sent me this model to do it.”

D. “How old is he?”

A. “Seventy-eight or something like that… I asked him to reproduce this historical work of his, from 1968,” he tells us while we see the original work in a book. “This is used for the train tracks. This structure is needed to align the tracks. So, since it was very difficult to build that work, I kept this model.”

D. “Is he another of the post-war artists that interests you? Like Hiroshi Fujii24 (1942–)?”

A. “Yes, they are friends.”

D. “I must say that I didn’t know anything about Mono-ha25 before I investigated you, Akira. It was there that I discovered the movement.” (“Mono-ha” is usually translated in a literal manner, as “School of Things". Art movement based in Japan, active from around 1968 to 1975).

A. “I have more things, 4, 5, 6…,” he counts mentally.

D. “Bring them, please.”

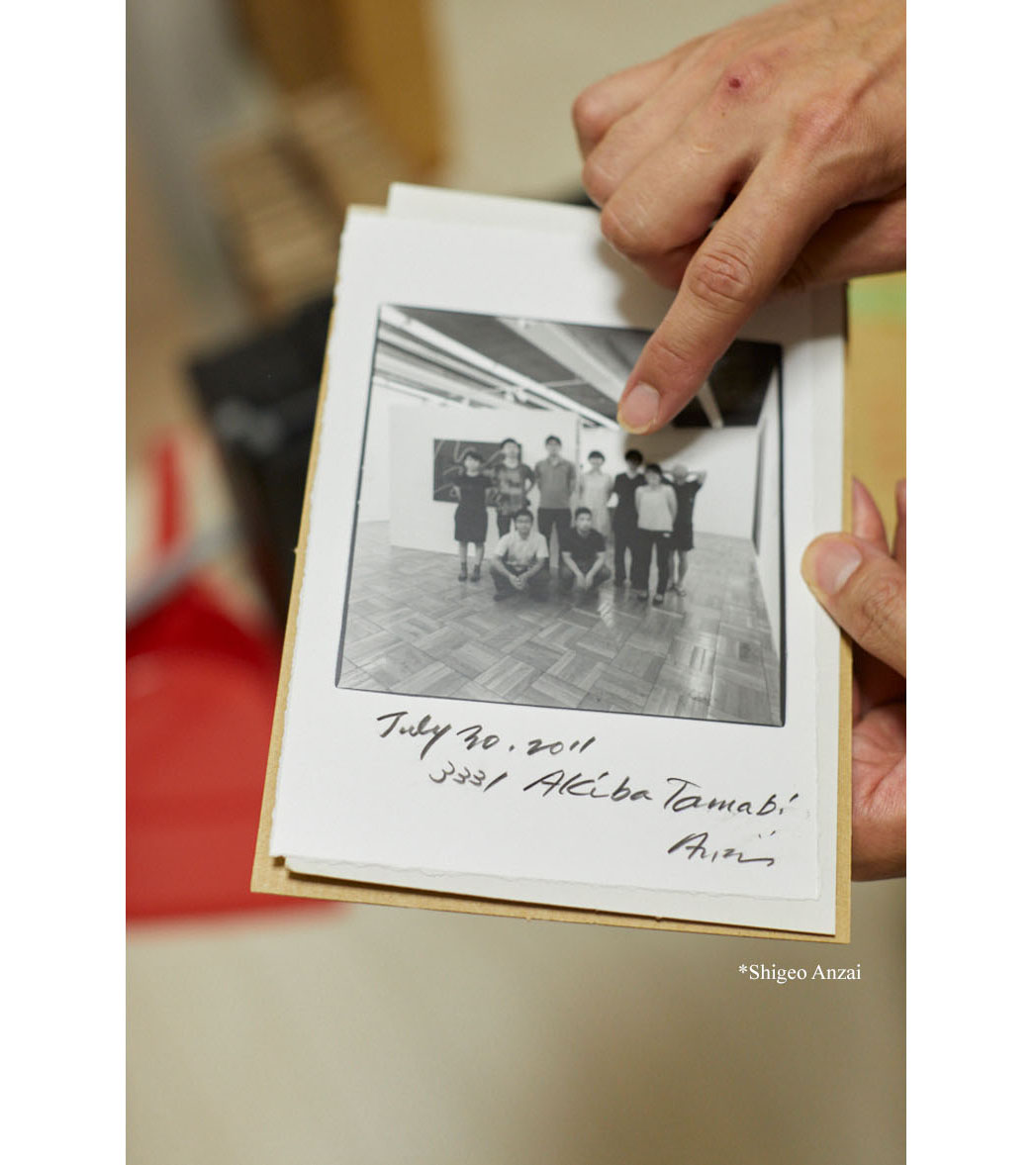

Among various objects appears a photo by photographer Shigeo Anzai (1939–2020)26.”

M. “He is a well-known photographer, especially famous for his portraits of many artists and his documentation of their artworks between the 1970s and the 2000s.”

D. “I was reading that he was linked to the Mono-ha movement, right? Many of the works that disappeared have a photographic record thanks to him.”

M. “Yes, that’s true, but he’s not a Mono-ha artist, but rather a portraitist of those artists. In this photo, he made a portrait of us.”

A. “This is Maiko, this is me and this is Daichi,” he says as he points his finger at each one in the black and white photo. “We are in a gallery linked to Tama Art University.”

D. “So, it’s a group exhibition, and he took a photo of you, is that right? Was he a professor at the university?”

A. “Yes, that’s it. He came to the show.”

M. “He was very generous, even with the students. He took a photo of us, printed it and gave each of us a copy, with his signature.”

D. “He passed away two years ago.”

M. “Yes,” she says affectionately.

A. “Imagine that back then, artists linked to Mono-ha were unknown. Anzai had that same attitude. He portrayed what was happening at that time.”

D. “What other treasures do we have in the studio?”

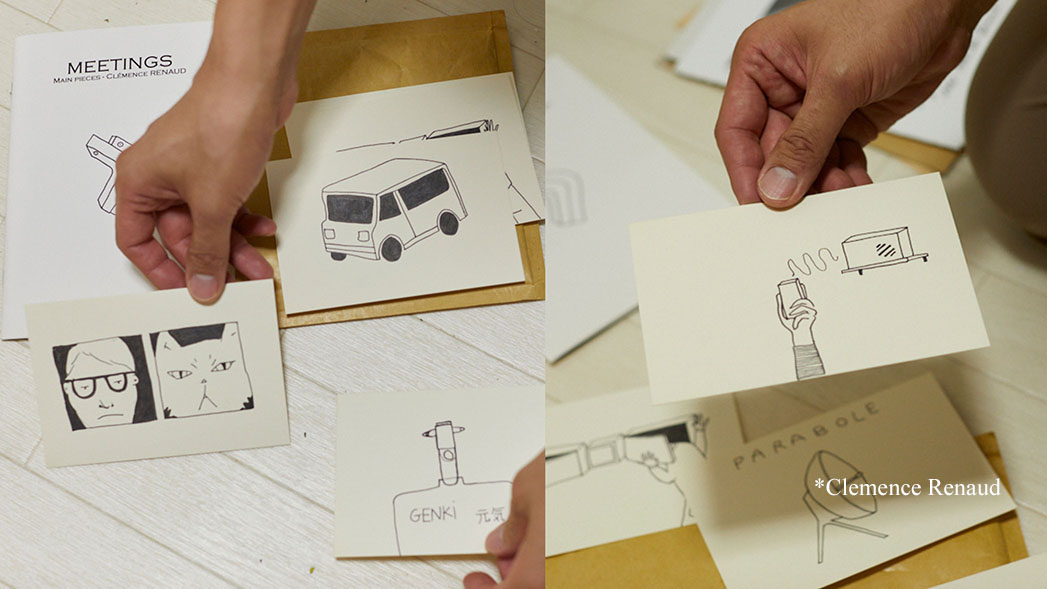

A. “Clemence Renaud27.”

D. “Oh yeah, I saw you in her video, on her website.”

A. “Exactly. These are drawings of that work, this is me. The video was made here in Tokyo.”

In the video Gloires et déclins (2018) we see different images of Tokyo following one another along with a series of messages, voices, and the unmistakable (and powerful) sound of cicadas in summer. The human bodies are replaced by various wireless objects that transmit information (a radio, a router, a mobile phone, a GPS, a satellite). In the tour of images that takes us to the artificial island of Odaiba, the only human body we see is Akira’s.

D. “What are you holding in your hand, a tape recorder?” I ask, pointing to the drawing.

A. “It’s more like a white box, but it represents a smartphone or something.”

At some point we take a break and sit at the table, or on the floor on the tatami, which in Japan is the same. Sara is on her “lunch break,” Akira opens two baby food jars, she seems interested in only one of them, she makes funny faces every time he approaches a spoon to her mouth with the other one. He doesn’t give up that easily, continuing to gently offer her the spoon as we chat. We tasted a few sweets I bought on my visit to Matsudo, a city less than an hour from central Tokyo. The day before every interview I take care of buying sweets to share. I try to choose different things to taste and also as an excuse to talk about Japanese sweets. Akira offers us green tea and cuts the sweets into four halves so we can try each thing. That gesture is familiar to me and gives me a certain joy.

D. “How did you guys meet?”

A. “I think it was when we were 19.”

M. “No, before, we were 17, we were high school students.”

A. “We met in the preparatory course for university, where they prepare you to take the admission exam.”

D. “So, in the end you entered different universities. Maiko went to Tama and Akira to Musashino, right?”

M. “Yes, that was the result, it happened like that. At that time, we were still just friends, we weren’t together yet.”

D. “When did you start dating?”

M. “When we were 23 I think, or 22, when we were in our third year of university.”

D. “The two universities are in this area, right? Have you always lived around here?”

M. “Yes, it’s close. At first, I lived with my mom, then I moved near the university. And he did the same. For example, if you want to stay late at the studio, it is better to be close.”

D. “I have a silly question to ask you, but I learn a lot from the answers. What artist would you buy the work of if you could?”

A. “Well, we already have a Picasso,” he answers quickly, and laughs.

They think briefly.

A. “If I had money, I would buy works by my artist friends. Our friends are amazing artists.”

D. “It’s a good answer.”

M. “Yes, it is a good answer. In fact, when you contacted me for this interview, I had never thought about my collection, and it was interesting to do so. In the last decade we traveled a lot, so I tried not to have many things. We were very nomadic at the time. I thought of the place where we lived as a temporary place. Akira had more things. I didn’t have a proper collection, but I did have some works from friends. During the pandemic I began to think about staying in a place that was comfortable, so I began to hang some work. And I realize that living together with the works has a great effect on me. Gives me energy. It made me think that I should have more works, especially by women artists, because we had a lot of men’s pieces. It was a good opportunity to think about those works.”

D. “Do you think that you have a collection?”

M. “Before you asked me, I never thought I had a collection. I also began to wonder what things can be a work of art. For example, debris that my friend brought from Mexico is a work for me.”

D. “Going back to the university years, what orientation did you choose? Because on Tama’s website I didn’t see any specific film or video program, and I was wondering how you got there.”

M. “Oil painting, because if you choose that, it means you can do anything, contemporary art, video. Likewise, I had to learn a lot on my own, and the teachers accepted it. There was a video production department, but on another campus, and classes were generally held at night. I heard that departments having classes at night had been eliminated after my graduation.”

D. “Akira, you also choose oil painting, right?” I highlight this because in Japan the other option is Nihonga, literally “Japanese-Style Painting.”

A. “Yes, yes.”

D. “But well, it’s clear that you’re a painter, and I don’t know how you call the installations with holes in the ground. How do you call them?”

A. “At the beginning they were more like a research project for me, from the time when I was studying Mono-ha. I needed to dig those holes myself. I felt a great connection while digging those holes. Mono-ha is a well-known movement in post-war Japan, but the idea of them is a bit limited, narrow, just stones, glass…. you know.”

D. “While I was researching about you guys, the presence of the ‘hole’ in your works caught my attention. On one hand, on Akira’s side it’s also related to his interest in writer Haruki Murakami. In a very different way, the hole also appears in Maiko’s video A Distant Duet (2016), in the story of a boy who falls into the hole. And Maiko is clearly interested in writer Roberto Bolaño, who appears a lot in her work, in some performances such as Reading of 2666 (2016). I wonder, how did you get to him? Or what interests you about his work, Maiko?”

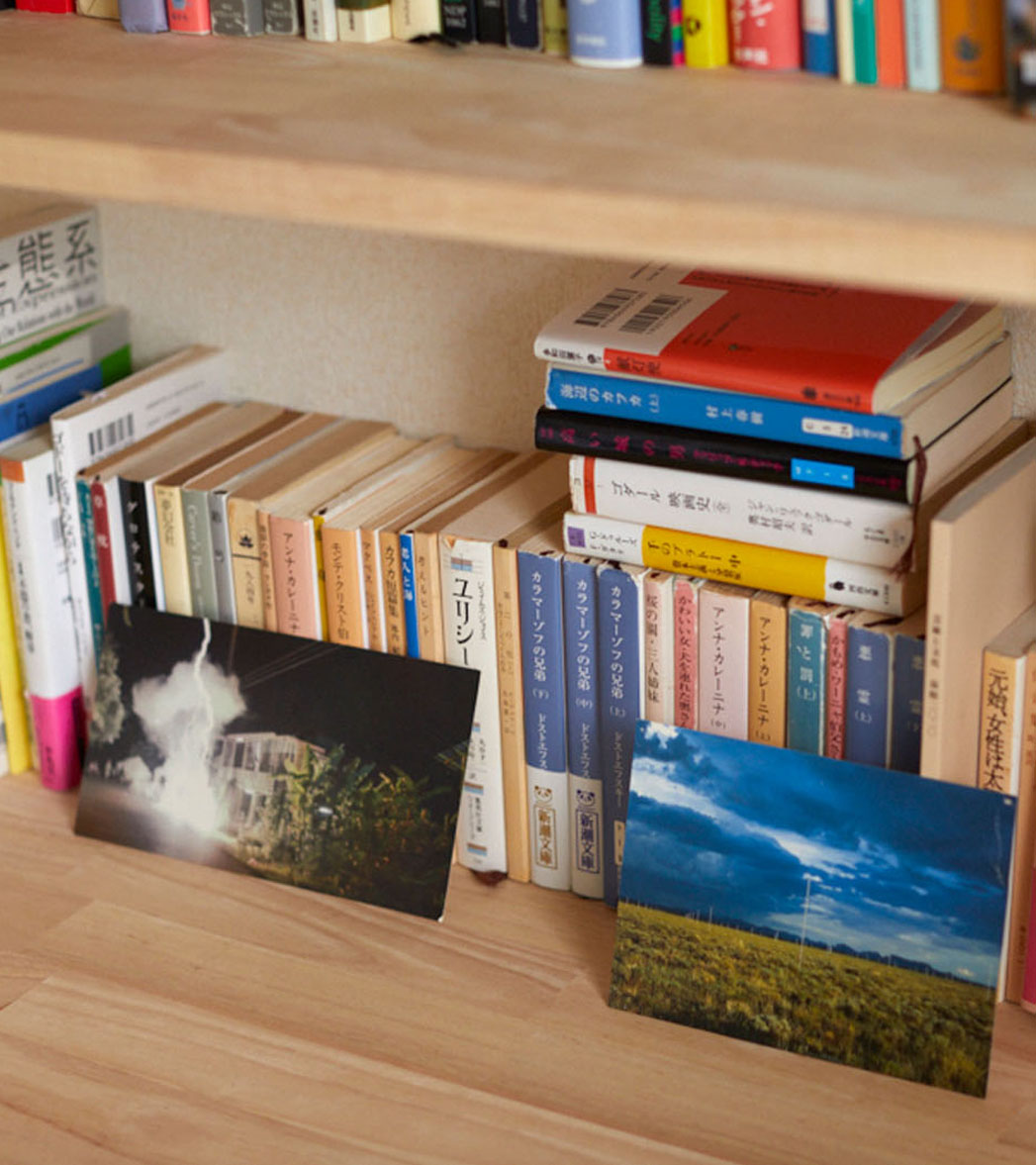

M. “The first time I came across a book by Bolaño was in a bookstore, and the cover caught my attention. I opened it and was fascinated from the first sentence. There was a deep connection, so I bought it. I think it was the first translation of his work that we had in Japan, later other books appeared in Japanese. The ‘hole’ thing is not a coincidence. We both participated in a group show that inquired into what happened in 1968, which Akira just told you about. Oh, now I forgot how we got to the ‘hole’ thing.”

A. “It all starts with the hole dug by Koji Enokura (1942-1995)28, one of the Mono-ha artists.”

M. “Ah yes, he dug a hole.”

A. “I didn’t know at first that he had dug a hole, and he is a well-known artist today. But early in his career, he made these holes and later he developed his style for which he was most recognized. Discovering those images changed my way of understanding it, because I did not know those early works and I connected with those works.”

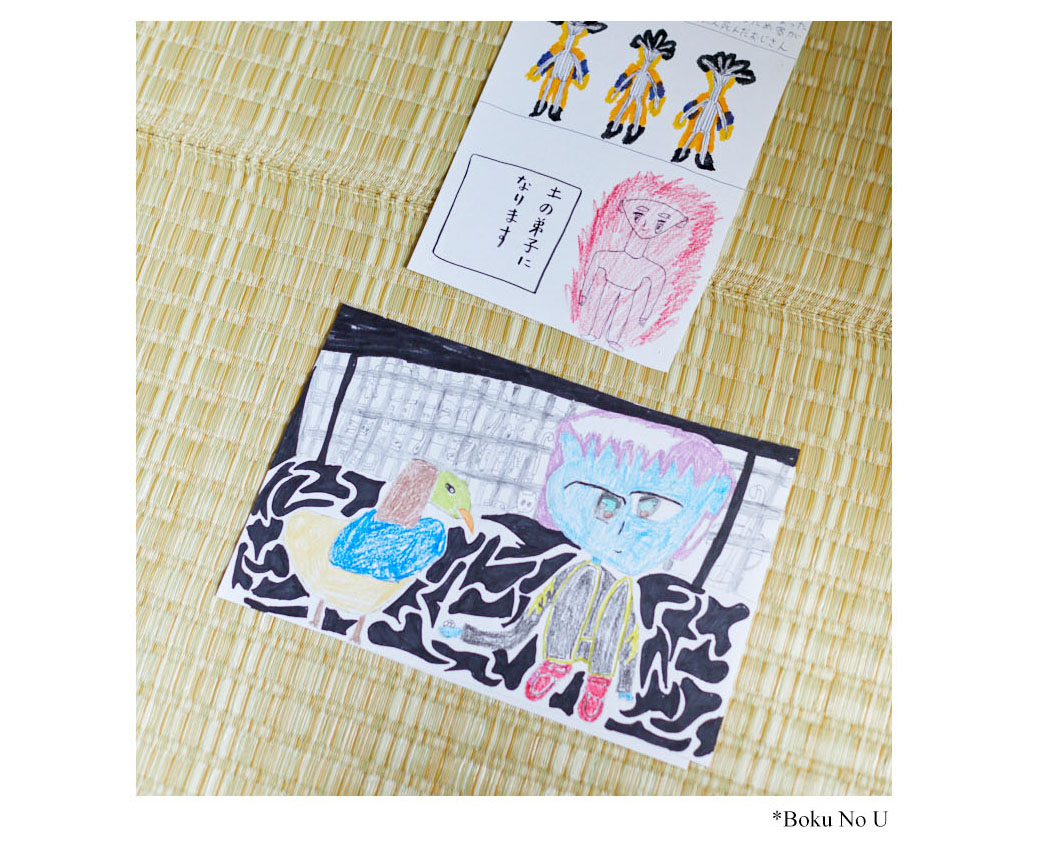

M. “The exhibition we did, My Hole, Holes in Art29, started from our interest in what actually happened around 1968, and in why some artists dealt with a hole as their subject in that era. In 1968, revolution and student movements occurred in many countries. In Japan too, there were huge student protests in universities. Koji Enokura and other Mono-ha artists were young at that time. Their works seemingly did not have a political background, but we thought there must be a certain influence of the social conditions. Koji Enokura, Noboru Takayama, Hiroshi Fujii dug a hole in November of 1970 at a property where Takayama lived. In the same winter, a protagonist of a novel by Haruki Murakami dug a hole. Well, one happened in the real world, and another happened in the fictional world. But this is a mysterious link. Haruki Murakami is a bit younger than Enokura, but they are almost of the same generation. There is another coincidence. In 1968, there was a big student movement in Mexico City that clashed with the police. Police occupied one of the universities violently. Bolaño wrote about the incident in his most famous novel, The Savage Detectives. He wrote about a deep hole in a different chapter in the same novel. I was fascinated by the connection, and wanted to know why a hole, what a ‘hole’ is. My work A Distant Duet was an attempt to have a conversation with Bolaño, who has already passed away, and try to understand what a ‘hole’ represents.”

D. “Do you like Patti Smith?”

M. “Yes!”

D. “She is also a big fan of Bolaño.”

M. “Is she?!”

D. “She said that she spent two years reading and deconstructing the book 2666, from back to front and from all angles.”

A. “She also adores Murakami.”

D. “That’s the connection, ha ha.”

M. “Oh, something I should have mentioned at the beginning is that, in 2011, the great earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster occurred in Japan. And my idea of community and country changed a lot. Before that I had never questioned myself if I belonged to Japanese society, but then it started to seem strange and odd to me and I couldn’t feel part of it anymore.”

D. “Art is often a refuge.”

A. “Offers an alternative. Somehow you can change reality.”

D. “Nozomu said the other day, when I visited him at Ongoing, ‘Being an artist is like being an activist.’”

M. “In Japanese society, being an artist is considered something rare. If I tell someone that I’m an artist they think it’s weird; maybe it’s the same in all societies, but artists all over the world somehow speak the same language. I think there is a global artist community in some way.”

D. “The stories I’m hearing in the Japanese interviews are very similar to those of Argentina. The sense of artistic community, friendship, peer recognition.”

M. “That gives me air, it allows me to breathe.”

D: “One last question. Do you think in Japan it is possible to make a living in art, or is it necessary to have a second job to survive?”

M. “It depends a bit on your luck, ha ha.”

D. “I guess for video artists it is even more difficult.”

M. “Yes, it is more difficult. Masaya Chiba just invited me to teach at Tama Art University and I realized that the professors have good fees and it is possible to live only on that. My position is a part-time lecturer, so not the case though.”

D. “You also have galleries that represent your work. What is yours, Akira?”

A. “I’m just leaving the gallery, I realize it’s better for me to sell alone.”

M. “I sold some works, but it’s not something that happens often, so it’s hard to live just on that income. Sometimes I get a scholarship, which isn’t enough either, but… now, for example, I’m teaching at the university. It’s not a lot of money, but it’s something. Akira works as an installer, as a part-time job.”

A. “I started making holes for my work, and gradually acquired the technique. It is very difficult to dig, actually.”

M. “Sometimes I work with friends editing and filming.”

D. “Sure, the same thing happens in my country. I was asking because I thought maybe Japan was different.”

A. and M. “No, no, not at all!” they respond in chorus.

A. “It’s a bit… suicidal, ha ha.”

M. “A few days ago I saw a tweet from someone I knew a long time ago, someone who used to teach, and he said that he had to go to a food bank three times this summer because he couldn’t make it. With the pandemic, the war, the increase in prices, and with the same salary, it was not enough. It’s not enough anymore. He must be fifty years old or so and his parents depend on him. I thought about my future…”

MS. “In your next life, would you also choose to be an artist?”

M. “Yes, I don’t regret it, never.”

MS. “Many people who have other professions, who work for big companies, have some kind of admiration for artists, they often think ‘Oh, I would love to be an artist.’”

D. “An idealization of what it means to be an artist.”

MS. “Sure, but they don’t have the guts to do it. So, I wonder if artists also fantasize or would like to do something else.” We all laugh.

A. “Yes, I understand. I actually knew that I wanted to be an artist from the age of 4 or 5.”

D. “You are also a curator sometimes. Chatting recently with a curator and artist from Buenos Aires, Santiago Villanueva, he said that first an idea occurs to him, and then he thinks if it can be transformed into a curatorship, or a work, or a book, etc.”

A. “In my case, curatorship has to do with my work. It is like preparation for my work. In some way, my work as a curator helps my work as an artist to be better understood.”

M. “Create a context.”

D. “What you do as a curator is clearly related to your work, I can see that.”

A. “Yes, but my work comes first. Sometimes I find the lack of context frustrating, and it has to do with that. The art history is already written, but those narratives are made by someone. So, I try to write other stories too, other narratives, using my own words30.”

M. “Marisa, what would you have been if you weren’t a photographer?”

A cute kid’s music plays in the background from one of Sara’s toys.

MS. “When I was in high school I wanted to be a graphic designer, but before that I had the fantasy of being a rock star.” Chorus laughter. “I can’t sing, but I like to see people singing on a big stage, and it must feel amazing. Maybe in the next life, if I make it. I enjoy photography, I have the fantasy of being an artist.”

D. “But you are an artist! There are many ways to be an artist.”

MS. “I want to be, but sometimes I wonder what it is to be an artist. I think, I think too much, I would like to think less, like children when they do something. And there are many artists now who are doing good things or not so much, but who is one to judge?”

D. “Well there are different art scenes, with different audiences. I think that Maiko and Akira belong to a scene that has to do with my own interests, for example.”

M. “I’m very happy that you found us,” says Maiko with a very tender voice, and I think that I’m very lucky to be there.

D. “Well, when I checked Hagiwara Projects31, your gallery’s website, and I started looking at the artists. I immediately liked your work. And then when I saw in your CV that you had been in residence at El Matadero, in Spain, I thought, ‘She’s the one, she will surely answer my email.’”

M. “Well, many people don’t understand what we do, but there are a lot of people who do and are interested.”

D. “Unlike the group of artists that I interviewed in Buenos Aires, I think that every artist that I am interviewing in Japan belongs to a different art scene. Yuna Ogino belongs to one scene, Tomoki Watanabe to another. Kenji Ide and you guys are on the same one, I’d say.”

A. “And every scene has its own community as well. I imagine that the same thing happens with music.”

D. “Of course; you, Maiko, for example, also work with musicians in your performances and videos. With drummers. There is also a musician in your collection, quite famous: Yamantaka Eye32.”

M. “Ah yes, very famous!”

They go to the other room to look for the vinyls and bring them to the living room.

D. “Where did you buy these works?”

A. “In a gallery, someone curated the exhibition. But I don’t know him personally or anything. This is a collage by Eye.”

D. “He does the covers of these records, right?”

A. “Yes, they are more like products. We don’t know him personally, but he’s quite famous, we like what he does. And we buy these records that are pretty rare vinyl. They cost us 6,000 yen (43 dollars), a value that, as art, is not much, they are records, basically.

Sara is already calling for attention, she behaves excellently, but I guess she is tired of having her parents’ attention focused on the interview.

D. “I promise we’ll leave soon, Sara…” I say to her more than once.

MS. “There is more collection coming.

D. “They have quite a large collection.”

M. “Do you think so?” [Laughs]

D. “Well, Yuna Ogino has about 10 works, Tomoki Watanabe has a few more but they are very different. He collects works that are a sort of dolls, and small figures.

M. “Oh, anime-like?”

D. “Hmm no. How to describe them?”

M. “Gacha Gacha?” (Refers to vending machines that sell small toys inside a capsule. Gacha gacha is another onomatopoeia; the sound produced by turning the machine's crank twice.)

D. “What is Gacha Gacha?” They discuss something in Japanese. Marisa explains that they are more like small sculptures.

D. “We’re leaving soon, Sara,” I tell her as she rehearses a few syllables and smiles for us when Marisa focuses her camera on her.

M. “I think Sara is joining our conversation.”

MS. “She has all the answers.”

FOOTNOTES

1Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

2 Maiko Jinushi: http://maikojinushi.com/

3 Akira Takaishi:http://www.akiratakaishi.com/

4 Nicolás Pellizer: @_duiyo

5 Syafiatudina: https://dinamakan.online/about

6 Wok the rock: www.goethe.de/prj/nus/en/ats/wtr.html

7 Kunci: www.kunci.or.id/about-us

8Art Center Ongoing: https://www.ongoing.jp/

9 Kenji Ide: @works_kenjiide

10 Boat Zhang: http://www.boatzhang.com/

11Hinamatsuri, Hinamatsuri, also known as Doll’s Day or Girls’ Day, is an annual festival in Japan held to celebrate the health and happiness of female children and femininity in general.

12Tanabata or Star Festival is a holiday derived from the Chinese Qi xi tradition “The Night of Sevens.” It is tradition to write Tanabata wishes on strips of colored paper and hang them on trees made of bamboo branches. According to tradition, this is the only day of the year when the two stars, Altair and Vega (representing two lovers) can meet.

13Sara Gassmann: https://www.saragassmann.ch/

14 Ryuichiro Otake: @ryuichirootake_studio

15 Fumiaki Akahane: http://www.fumiakiakahane.com/

16 Gyoji Nomiyama: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14108946

17 Morikazu Kumagai:http://kumagai-morikazu.jp/

18 Kenjiro Okazaki: https://kenjirookazaki.com/eng/

19 Masaya Chiba: https://shugoarts.com/en/artist/143/

20 Super Open Studio: https://www.superopenstudio.net/

21 Daichi Takagi: https://daichitakagi.net/

22 Meriem Bennani: http://meriembennani.com/

23Noboru Takayama (1944-2023). See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/subterraneans-and-mirrorless-mirror/

24In 2018, Akira Takaishi and Tomohito Ishii curated an exhibition called My Hole: Scab of the 21st Century at Space 23℃, a small art space, set up in the garden of artist Koji Enokura’s widow’s house, in the residential area of Todoroki. Four works by Fujii (1942–) made between the 1970s and the 1990s were shown there.Regarded as a forgotten Mono-ha artist, a writer who developed his activity in the same period as the Mono-ha artists, he was not properly historicized within the Japanese art world.In the curatorial text for the exhibition, Akira wrote: “The practice was more critical than the writers of the same era, and it cut through the outline of the body of art. Fujii’s work is not the core hardcore of Japanese contemporary art, but the hard film formed at the boundary between the inside and the outside, the core crust core of the scab”. See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/my-hole-scab-of-the-21st-century/

25Mono-ha (も の 派) is the name given to an art movement that has its origins in the mid-1960s in Tokyo. It is generally translated as “School of Things”, a term coined with disdain by critics in Bijutsu Techo magazine, long after he began exhibiting his work. The Mono-ha artists did not start out as an organized collective. They investigated materials and their properties in reaction to ruthless development and industrialization in Japan. They explored the encounter between natural and industrial materials, such as stone, steel plates, glass, light bulbs, cotton, sponge, paper, wood, wire, rope, leather, oil and water, ordering them mostly unchanged. They share characteristics of the Land Art movement, Fluxus and Conceptual Art. One of the most recognized artists is Korean Lee Ufan (1936), a decade older than the rest, who settled in Japan at the age of 20. Some artists are: Nobuo Sekine (1942–2019), Katsuro Yoshida (1943–1999), Susumu Koshimizu (1944–), Koji Enokura (1942–1995), Kishio Suga (1944–), Noboru Takayama (1944–) and Katsuhiko Narita (1944–), Jiro Takamatsu (1936–1998), Shingo Honda (1944–2019).

26https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/shigeo-anzai-24656

27 Clemence Renaud: https://www.clemencerenaud.net/ and the video here: https://www.clemencerenaud.net/gloires-et-declins

28 Koji Enokura: https://www.takaishiigallery.com/en/archives/17458/

29 In 2015, five artists born in the early 1980s, Akira Takaishi, Maiko Jinushi, Tomohito Ishii, Tomohiro Masuda, and Saeka Enokura, held the My Hole, Holes in Art exhibition in a house. Makiko Hara writes: “In re-examining the meaning behind the 'holes' in Haruki Murakami's writings illustrating the turning point of post-war Japan in the 1970s, and the meanings of the 'holes' that many artists were digging at the time, those artists featured here aimed to survey their own 'holes' in 2010s reality.”". See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/my-hole-hole-in-art/

30 Following the series of exhibitions related to Mono-ha artists that we listed before, I find three exhibitions that occur simultaneously in 2019: Hole: Hole in Art Series. On one hand, we have Indeterminate area with works by Koji Enokura (1942–1995), Noboru Takayama (1944–) and Hiroshi Fujii (1942–) in Space 23ºC, then the solo show Pleasure Plane by Tomohito Ishii in Capsule, and finally Akira Takaishi’s shows Descent Garden at Clinic. Let’s remember that Ishii and Takaishi also participated in the group exhibition My Hole, Holes in Art (2015) and had already curated together the exhibition My Hole: Scab of the 21st Century by Hiroshi Fujii (2018). See: https://myholeholesinart.jimdofree.com/my-hole-hole-in-art-series-2019/

31Hagiwara Projects (www.hagiwaraprojects.com) is a gallery located in the Kōtō ward, Tokyo. It represents artists Miho Dohi, Yuta Hayakawa, Shunsuke Imai, Tomotsu Kido, Ryota Nojima, Nobuhiko Nukata, Zak Prekop, and Maiko Jinushi. I visited the space during the opening of the Onsen Confidential group show, organized with the Crevecœur gallery from Paris, and had a few words with its friendly director Yukari Hagiwara.

32 Yamantaka Eye: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yamantaka_Eye