FOOTNOTES

1Kenji Ide: @works_kenjiide

2Maiko Jinushi: http://maikojinushi.com/

3Goya Curtain is a non-profit art and project space created in 2016 by Joel Kirkham and Bjorn Houtman. Located in Shimo-Takaido Ward, Tokyo, it periodically hosts exhibitions and projects by local and international artists: http://goyacurtain.com/home.php

4Kenji Ide, Banana Moon, Watermelon Sun (Landmarks), 2021, at Goya Courtain: http://goyacurtain.com/kenji-ide.php.

5Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

6Bunchi: https://www.chanchokiu.com/home

7Humo Books: https://humobooks.com/

8Tsukimi means “to contemplate the moon.” Like hanami in spring and momiji in autumn, this Japanese festival pays homage to nature: the autumn moon. Since ancient times, Japanese writings have identified September as the best time to gaze at the moon, when the star is particularly bright. It is the ideal time to show gratitude for the year’s harvest and to demonstrate hope for the next one. This tradition came from China more than 1,500 years ago and became popular during the Edo Period (1603–1868). It consists of contemplating the full moon on the first day of autumn, and the following days. According to Chinese mythology, rabbits can be seen scurrying around the moon on that day, a belief that in turn comes from Buddhism. In Japan it is common to see a rabbit kneading a mochi with a mallet (a typical Japanese sweet Tsukimi dango). The kneading of the mochi is called in Japanese mochitsuki (餅つき) and coincides with the Japanese pronunciation of the word full moon (mochitsuki 望月). During the celebration, wishes can be made, tea is drunk, and music is played/listened to.

9Kenji Ide’s exhibition, A Poem of Perception (2022), curated by Matt Jay, Tanabe Gallery, Portland Japanese Garden: “Ide is interested in the passage of time, both for the weight it carries in our everyday lives, but also for its connection to the experience of a Japanese garden. Drawing inspiration from his belief in the beauty of everyday life—the materials in Ide’s work are familiar and commonplace, creating an accessible visual language that is quietly powerful in its emotional familiarity. For example, Ide views the postcards incorporated into his installation as antiquated sculptures of communication. Unlike today’s digital messages, postcards have their own unique shape, weight, and color. They possess a physicality that people can project their own emotions or experiences onto. As physical objects that must travel through time and space to reach their recipients, postcards foster contemplative dialogue across distances. In Ide’s work, and in a Japanese garden, things are best experienced when one takes their time to open their hearts and minds to be moved by the smallest details. See: https://japanesegarden.org/2022/08/30/kenji-ide-a-poem-of-perception/

10YUGEN / Tsukimi (2019) exhibition by Jiří Kovanda and Kenji Ide at Guimarães, Vienna. The space is directed by artists Christoph Meier, Nicola Pecoraro and Hugo Canoilas. The title contains two Japanese words, on the one hand Yūgen is a word that escapes simple definition, it is the core of appreciation of beauty and art in Japan. It values the power to evoke, rather than the ability to say something directly. “The yūgen is an aesthetic code originating in China that suggests that the work of art serves to give complete form to the inexpressible. Instead of making certain complex or nuanced emotions explicit, it suggests them,” writes Ana Kazumi Stahl in Miradas: literatura japonesa del siglo XX (Glimpses: 20th-Century Japanese literature), Colección Cuadernos, Malba Literatura, 2020. While Tsukimi refers to the celebration of the full autumn moon: to look at, observe or contemplate the moon. The exhibition text is the lyrics of Mitchell Parish’s 1939 song Moonlight Serenade. “I stand at your door and the song I sing is of moonlight / I stand and wait for the touch of your hand in the June night / The roses are sighing a Moonlight Serenade / The stars are lit and tonight how their light makes me dream / My love, do you know that your eyes are like stars that shine bright? / I bring you and sing you a Moonlight Serenade / Let’s wander till dawn in the valley of love’s dreams / Just you and me, a summer sky, a heavenly breeze kissing the trees / So don’t let me wait, come to me tenderly in the June night / I stand at your door and sing you a song in the moonlight / A song of love, my love, a Moonlight Serenade.” More information: https://www.guimaraes.info/yugen-tsukimi.html

11XYZ Collective: http://xyzcollective.org/current.html

12About the exhibition YUGEN / Tsukimi: “XYZ Collective: An Invitation to Shy People”: https://pw-magazine.com/2019/xyz-collective-an-invitation-to-shy-people.

13Jun’ichirō Tanizaki “… I was hesitating about the place I would choose that year to go to see the autumn moon and finally decided on Ishiyama Shrine, but on the eve of the full moon I read in the newspaper that, in order to increase the enjoyment of visitors who went to the mystery the next day at night to see the moon, a recording of the Moonlight Sonata had been placed in the woods. This reading made me instantly give up my excursion to Ishiyama … On another occasion I had already been spoiled by the spectacle of the full moon: one year I wanted to go to contemplate it in the boat at the Suma monastery pond on the fifteenth night, so I invited some friends and we arrived loaded with our provisions to discover that around the pond they had placed cheerful garlands of multicolored electric bulbs; the moon had come to the appointment, but it was as if it no longer existed,” In Praise of Shadows (El elogio de la sombra , Siruela, 2016).

14Nengajō: Japan’s efficient postal system allows all New Year’s greeting postcards to be delivered promptly on January 1 (although they must be delivered to the post office before Christmas). The message usually written on them is “Happy New Year! I hope this New Year brings you better luck, and thank you in advance for your help.” These cards, in addition to being delivered before that deadline, have to be marked with the word nengajō. Then, in order to be able to deliver the millions of cards stored during the previous days, part-time students are often hired in order to multiply the workforce on that day 1 where everything has to go perfectly. This system of receiving and sending New Year greeting cards has been in operation in Japan since 1899. Some of the most popular greeting messages in these New Year cards are: Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu (I hope to count on your kindness and support in this coming year); (Shinnen) akemashite omedetō gozaimasu (I wish you a happy beginning (of the new year); Shoshun/hatsuharu (early spring), that is, you wish that spring arrives soon, and with it the first flowers and the first crops, and of course: Kinga shinnen (happy new year). Source: www.japonismo.com.

15Ulala Imai: : www.ulalaimai.com

16Yu Nishimura: https://galeriecrevecoeur.com/artists/yu-nishimura

17Kayoko Yuki: http://www.kayokoyuki.com/en/

18Soshiro Matsubara: http://soshiromatsubara.com/cv.html

19Masaya Chiba: https://shugoarts.com/en/artist/143/

20Cobra: http://cobra-goodnight.com/cvcontact.html

21Art Center Ongoing: https://www.ongoing.jp/en/

22Ryoko Aoki: @rani2orion

23Akira Takaishi: http://www.akiratakaishi.com/

24Daisuke Takahasi: http://anomalytokyo.com/en/artist/daisuke-takahashi/

25Bunchi (Chan, Cho Kiu), Transition, 2021. See video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nk6hH9hw24Y

26Kenji Ide, Rittai 2 (2018): http://paaet.jugem.jp/?eid=461

27Shintoism is the indigenous religion of Japan, an animistic belief that today is so embedded in the customs of the Japanese that it is impossible to discern in some cases what is religion and what is tradition. In this regard, Soetsu Yanagi writes: “Since these utilitarian objects have to perform a common task, they are dressed, so to speak, in simple attire and lead modest lives. We can almost sense a sense of contentment in them as they greet the arrival of each new day with a smile. They work thoughtlessly and selflessly, performing effortlessly and unobtrusively whatever task they are given.” Soetsu Yanagi, The Beauty of Everyday Things (La belleza del objeto cotidiano, Editorial GG, SL, 2021).

28Hanayo: www.hanayo.com

29Maki Katayama: https://makikatayama.com/

30Masaya Chiba Exhibition, in Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery (2021): https://www.art-it.asia/en/top_e/admin_expht_e/214227/

31Junya Sato: https://www.hagiwaraprojects.com/2017-lightthroughthewindow

32Kohei Kobayashi: http://anomalytokyo.com/en/artist/kohei-kobayashi/

33In the preface to the Japanese edition of Tristes Tropiques, anthropologist, philosopher and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) shares a memory of his childhood and reveals his first love with Japan. His father was a painter, and following the Impressionists dazzled by Japanism, he collected in a box a huge number of Ukiyo-e prints that he gave to his son from the age of five. The Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) print ended up in a box, (which was transformed into a little house) playing the role of the landscape that would be seen from the terrace, and was filled with furniture and miniature characters imported from Japan that were available in a Parisian store in the first decades of the twentieth century. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Other Face of the Moon: Writings on Japan (La otra cara de la luna: escritos sobre Japón, Capital Intelectual, 2012).

34Sylvanian Families toys have been manufactured since 1985 by Epoch Co., Ltd., based in Tokyo, Japan, and distributed worldwide by various companies. The entire line is set in Sylvania, a fictional village somewhere in North America. Most of the families are rural middle class, and many of them own family businesses or have jobs, such as doctor, teacher, artist, news reporter, carpenter, or bus driver. They are designed in the fashion of the 1950s. They may live in large multi-story houses or in homes of their own based on the premise of a vacation home of sorts. The houses are very realistically designed and can be decorated and redesigned. The characters, grouped into families, originally represented typical forest creatures such as rabbits, squirrels, bears, beavers, hedgehogs, foxes, deer, owls, raccoons, otters, and mice, and then expanded to other animals such as cats, dogs, hamsters, guinea pigs, penguins, monkeys, cows, sheep, pigs, elephants, pandas, kangaroos, koalas, and meerkats. Most families consist of a father, mother, sister and brother, and continue to add family members from there, such as grandparents, babies and older siblings. Source: Wikipedia.

35Sylvanian families Biennale: http://xyzcollective.org/sylvanian-families-biennale-2017.html

36Masanao Hirayama: @masanaohirayama

37Welcome to Sylvanian Gallery: https://utrecht.jp/blogs/news/wellcome-to-sylvanian-gallery

38Yu Araki: http://yuaraki.com/

39Japan Style. Architecture, interiors, design. Tuttle publishing, Periplus edition (HK) Ltd. 2005

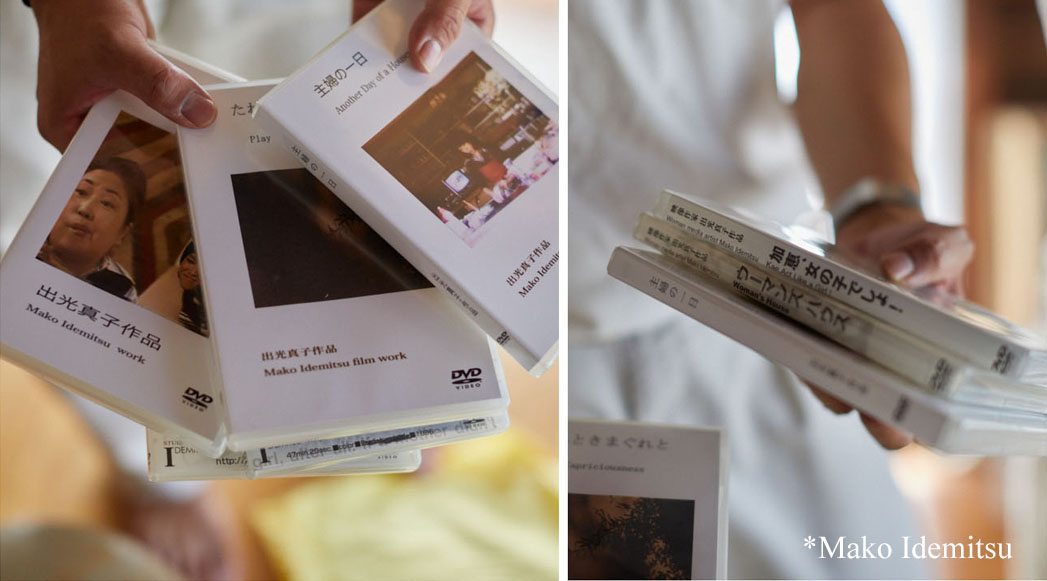

40Mako Idemitsu: https://makoidemitsu.com/ Mako Idemitsu: Japanese film and video artist, a pioneer of feminist art and visual expression in Japan. “Mako Idemitsu is a pioneer of Japanese feminist art and visual expression. She pursued study in New York following her graduation from Waseda University in 1962, in order to escape the control of her father, founder of the Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd. In 1965 she married the painter Sam Francis (1924–1994), moved to California and subsequently had two sons. However, due to the stress of being the wife of a famous painter, and the sense of isolation she felt as an Asian woman in American society, she began to feel that if she continued to do nothing, she would go utterly mad. Thus, she purchased an 8 mm film camera and began teaching herself to create video art. In 1970, she joined a consciousness-raising group tied to the then-flourishing Women’s Liberation Movement. With the encouragement of the groups’ members, she began using a more professional 16 mm camera.” By Reiko Kokatsu. Translated from the Japanese by Sara Sumpter at https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/mako-idemitsu/

41Yui Usui: https://yuiusui.com/

42About the video A Day in the Life of a Housewife (1977) by Mako Idemitsu: https://makoidemitsu.com/work/another-day-of-a-housewife/?lang=en

43Dollhouse (1972) by Miriam Schapiro: https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/dollhouse-35885

44Alpha M: Barokocho (gallery αM). The α in αM stands for “unknown quantity,” and the M, Musashino Art University. Oriented to contemporary art, it opened in Kichijoji in 1988. Special exhibitions were organized there, which functioned as a hotbed for new artists. It closed its doors in March 2002 and has since been transformed into “Project αM,” run by students from the university’s Department of Art and Culture. Unlike other artistic activities that prioritize commercial activities, this programming focuses on the art system itself and its artists. Moreover, in an art scene that tends to be influenced by economic conditions, galleries run by non-profit universities generate human resources and spaces of a certain quality, and play an important role in shaping the Japanese art scene. Source: https://gallery-alpham.com/

45Super Open Studios (S.O.S.) started in 2013 as a program of the Art Laboratory Hashimoto (where exhibitions of the participants are also held), operated by the city of Sagamihara. Two years later, the Super Open Studio Network coordinated by artists is formed and they take over the organization. In 2018, an executive committee was created, adding directors over the years. Some of them are: Pimp Studio, Lucky Happy Studio, Stack Room, Studio Kelcova, Moge Studio, Kunsthaus, Art Space Kaikas, Rev, Tana Studio, Studio Volta, Studio Ban, Shiatsu Studio, among others. There are single-artist studios and others with up to eleven members, generally graduates of the same university and career orientation. Although the Super Open Studios have been in existence for 10 years, artists began to settle in the area since the beginning of the 2000s.

46Takashi Murakami: @takashipom

47Yoshitomo Nara: https://www.yoshitomonara.org/en/

48Kunci: www.kunci.or.id/about-us

49Bijutsu (Fine Arts): It is a word that was born at the end of the 19th century in the context of the Universal Exhibitions. “Until the 19th century, the Japanese showed no interest in constructing an aesthetic theory,” writes Christine Greiner, and further clarifies that “unlike other terms relating to art, proposed by intellectuals or artists, Bijutsu (Fine Arts) was suggested by government officials, during the preparations for the renowned Universal Exhibition of Vienna (1873).” And she continues with this anecdote that I find quite didactic and amusing: “In the midst of these discussions and the first attempts to organize a proper lexicon for Japanese aesthetics, the Meiji government invited the orientalist Ernest F. Fenollosa (Japanologist, art historian, translator, and American poet) to give lectures on philosophy, aesthetics, art and literature at what would later become the Imperial University of Tokyo. … The translators recruited to interpret him in the lectures lived in crisis. They needed to improvise an arsenal of terms to translate what Fenollosa said, since, in Japan, the ideas of authorship and individual creation did not exist until then…” Christine Greiner, Readings of the body in Japan and its cognitive diasporas, Zettel Publishing Agency, 2018.

50Mingeikan: In Tokyo is the Japan Folk Crafts Museum. “We decided that we wanted to share the pleasure it brought us with others. We wanted to tell the story of a forgotten beauty of the past through everyday objects…,” Soetsu Yanagi, op. cit. See: mingeikan.or.jp/?lang=en.

51Mingei: folk art. The Mingei movement emerged in Japan in the 1920s, founded by the Japanese writer and philosopher Soetsu Yanagi (1889–1961) in collaboration with the ceramists Shoji Hamada (1894–1978) and Kanjiro Kawai (1890–1966). It seeks the valorization of products created by groups of anonymous craftsmen, as a response to the industrialization of Japanese society (due to Western influence) and as a reflection on the role of Japanese artistic traditions in a modernizing world. It was inspired by the English Arts & Crafts movement. “The objects of popular crafts … are made for everyday use … They are modestly priced products, produced in large quantities, not in limited editions, and their creators are not famous artists, but anonymous craftsmen. They are not conceived to give us aesthetic pleasure, but to be used on a daily basis.” Soetsu Yanagi, The Beauty of Everyday Things (La belleza del objeto cotidiano, Editorial GG, SL, 2021).

52Jirō Kinjō and ceramics from Okinawa: https://artsandculture.google.com/story/VgURWNXwhmclLQ

53The Nishi Ogikubo district is an antique district with many mini second-hand stores and galleries selling objects of all kinds and from different parts of the archipelago.

54Taichi Nakamura: https://www.taichi-painting.jp/

55Noriko Kawana: @norikokawana

56Genpei Akasegawa and Hi-Red Center, see: https://www.artforum.com/features/creative-destruction-the-art-of-akasegawa-genpei-and-hi-red-center-214960/

57Koji Nakano: http://xyzcollective.org/koji-nakano.html

58Hikari Ono: http://xyzcollective.org/hikari-ono.html

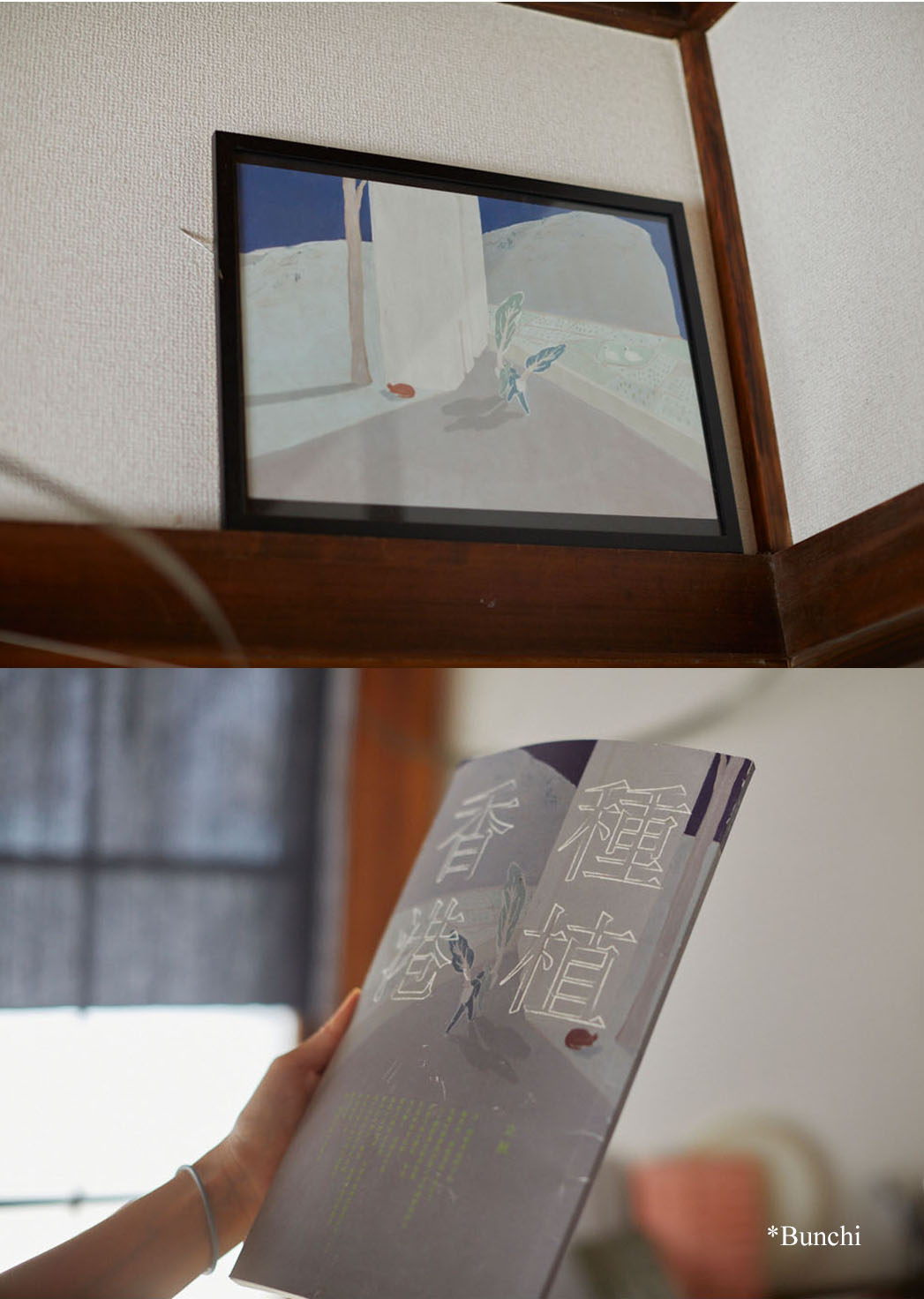

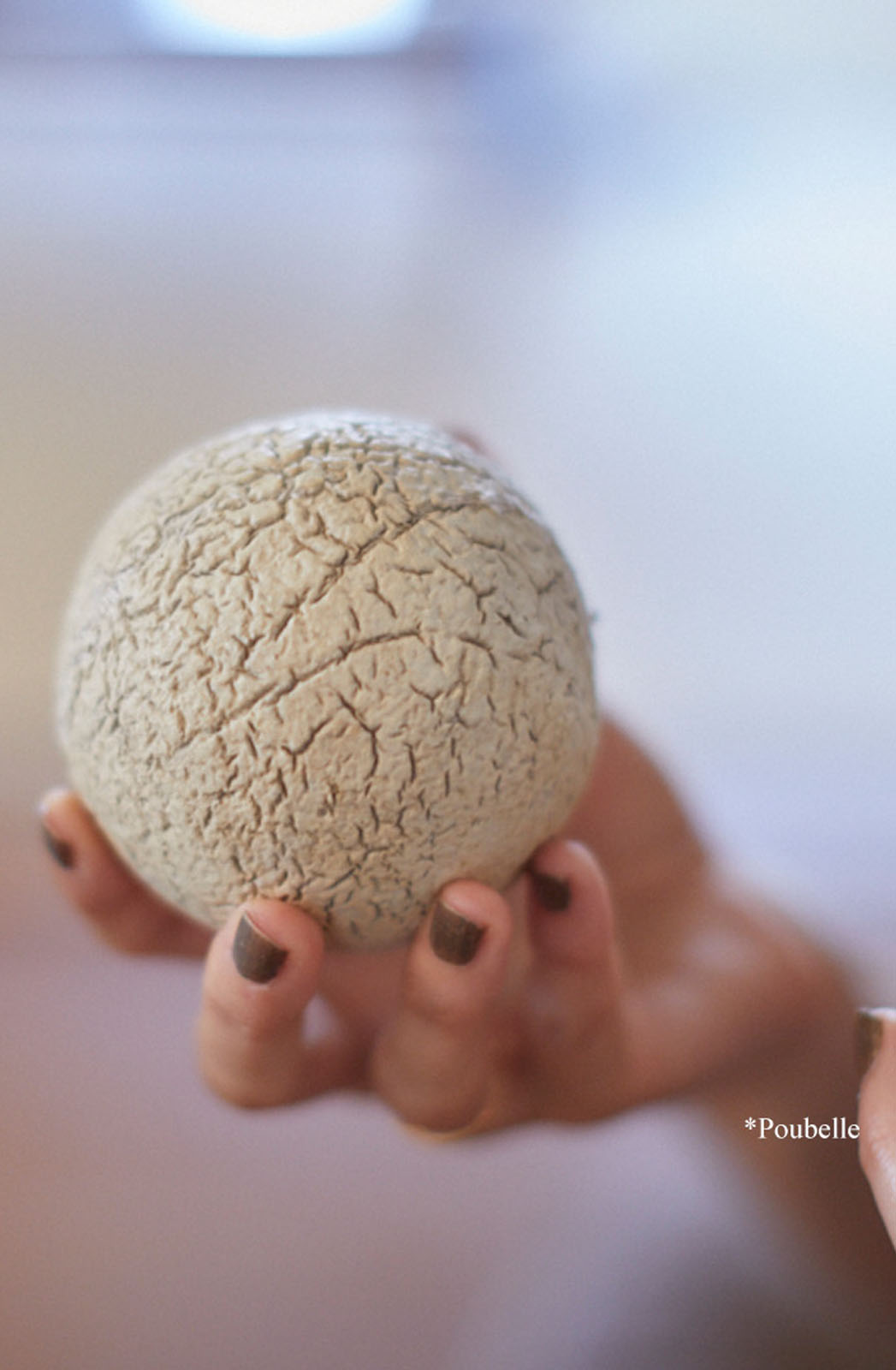

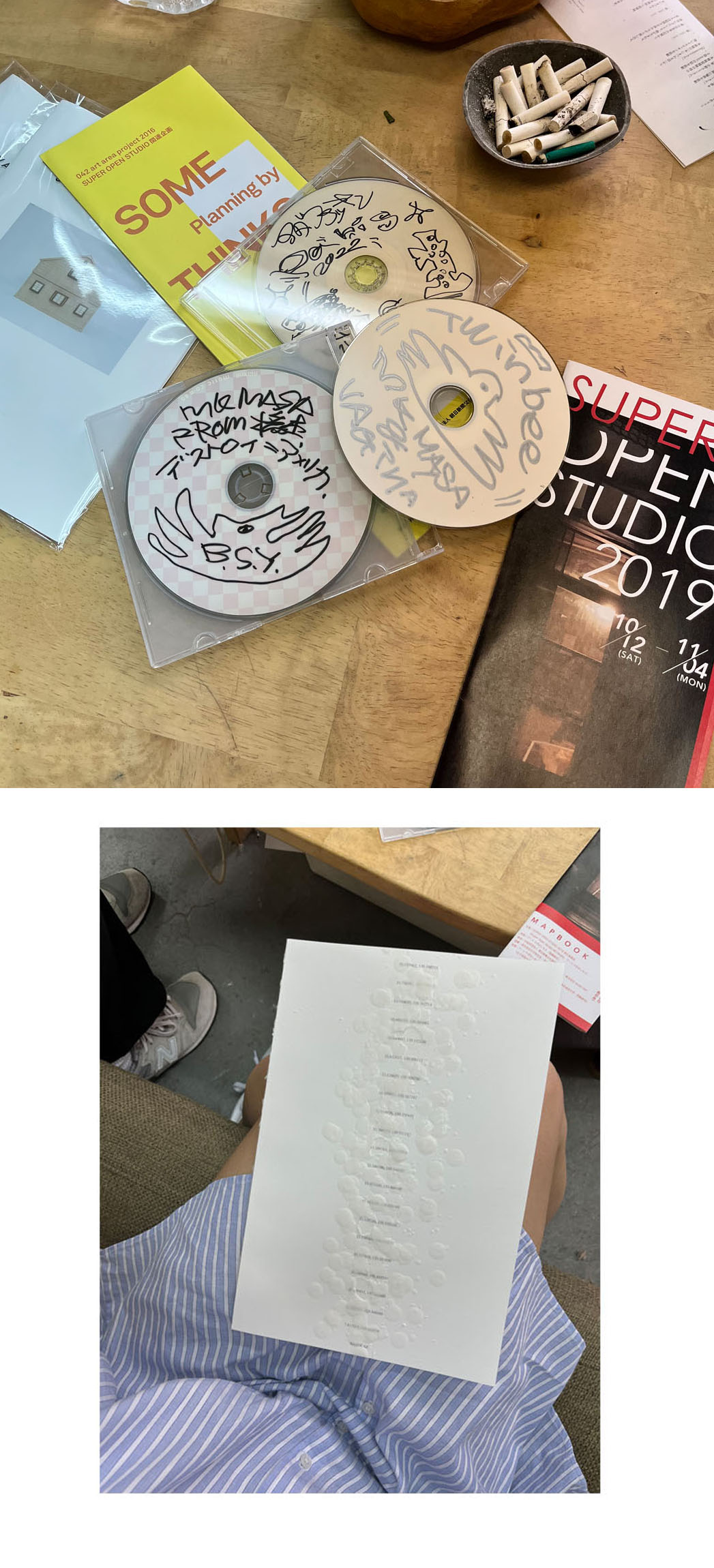

“This is another part of my collection, I have these works because they inspire me”

Kenji Ide and Bunchi

Kenji Ide (1981–)1 was introduced to me by artist Maiko Jinushi (1984–)2. They met fifteen years back, after graduated from Tama Art University. Before coming to Japan, Maiko passed me Kenji’s contact information and his Instagram account. After checking his photos, I wrote to her, “He seems like a funny person,” and she replied, “I’m surprised you can tell his character with so little information, ha ha. Yes, he’s definitely a funny person.”

Other colleagues present him this way: “Kenji Ide is an artist, family man, occasional rapper, and has been described by close friends as a romantic. He likes old things and recently traded his old car for a new old car. To bid farewell to his trusty Toyota station wagon he organized a group exhibition held inside the car titled Sayonara Mark II.”3

This description —on which we will elaborate in the next pages— can be read on the Goya Curtain space website on the occasion of his 2021 exhibition Banana Moon, Watermelon Sun (Landmarks)4. “In the case of Kenji’s work, big ideas become small, and our imagination goes to work; banana becomes moon, watermelon becomes sun, and so on.”

On the morning of the interview the Keiō line of trains takes me to Tobitakyū Station in the city of Chōfu, half an hour from central Tokyo. The station is neatly decorated with banners of the professional soccer teams F.C. Tokyo and Tokyo Verdy. A few blocks away, a large stadium (known as Ajinomoto Stadium) looms imposingly, and along the avenue I walk accompanied by the portraits of various Japanese players—among them, a Brazilian player named Leandro stands out. I sit down in the only open café, the Royal Host, next to the stadium, and while I wait for Marisa Shimamoto5, the photographer for this project, I order a coffee with some bread and jam. For some reason (still unknown) it comes with a lettuce and onion salad.

We parked Marisa’s car and looked around for the liquor store, the reference point indicated by Kenji. The house (no number) stands behind the store.

D. “Is it here?” I ask Marisa hoping she will guide us.

M. “Look,” she tells me, pointing out the outline of a painting in the window, and that is enough confirmation.

We ring the doorbell. We hear Kenji’s voice announcing to his family that we have arrived. The artist is married to Bunchi6 (her name is Chan, Cho Kiu, and she was born in Hong Kong in 1990). She is also an artist, and they have a five-year-old son, named To.

In a soccer neighborhood, hidden behind the store, there is then a traditional Japanese house that on the outside does not say much, but inside is amazing. “It must be from the fifties, after the World War II,” Kenji tells us leaning on the wooden crossbeam on which the fusuma slides in a typical Japanese gesture of this kind of old buildings, lower than the current ones, “the rental price is quite convenient for us, I mean it’s cheap.”

Built with fragile and temporary materials such as wood, the traditional Japanese house discards the non-essential and seeks beauty in humble materials. The scale and proportions arise from the dimensions of the human body, fixed in the module of a tatami (mat covering the floor, traditionally made of rice straw and reed with cloth borders) of 90 x 180 cm, the right size for a Japanese person to sleep on. The size of a room is then given by the number of tatami mats it can contain.

The few walls that exist are lined by a cream-colored wallpaper with a subtle lattice relief, the rest of the partitions, the fusuma (sliding doors) and the shōji (movable screens), are sliding wooden panels with rails above and below. They can be slid or dismantled like children’s toys and transform the space and dimensions of the room. The lighting in these homes is filtered and diffused. The white paper of the shōji doors lets in a screened reflection of outside light (but not the view).

The first dialogues with Kenji in the kitchen confirm some suspicions: “You’ll see that I can be very determinant when I say something, but I can also change my mind quickly, ha ha,” he says. Kenji speaks with confidence and moves with a certain urgency, Bunchi, on the other hand, speaks more quietly and slowly.

On the kitchen counter there is a calendar, a must in any Japanese household. In the month of September, a couple observes the full moon; next to it, the ears of corn representing the harvest and a tower of mochi dumplings typical of the celebration (the Tsukimi Dango, sweet rice, even has its emoji on WhatsApp).

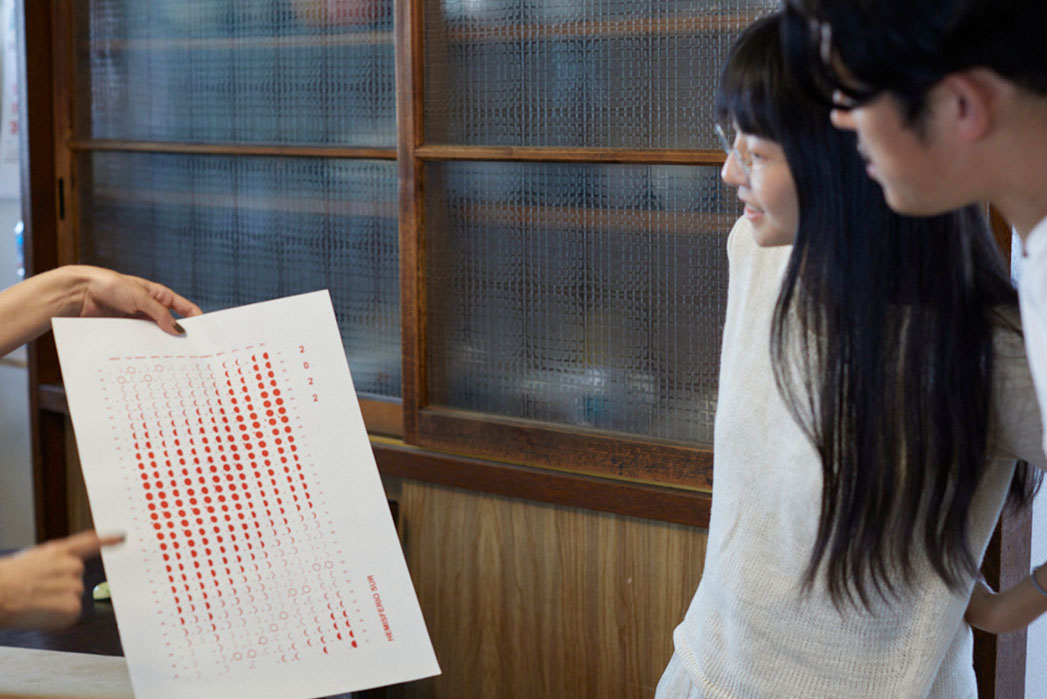

D. “I brought you the Humo Books7 southern hemisphere lunar calendar as a gift. I chose it because I was very surprised by the exhibition you did at Guimarães in Vienna, and from what I saw, the full moon of September was a few days ago.”

K. “Yes, that’s right, the Tsukimi8 (moon gazing), let me see,” he says while checking the phases of the lunar cycle on the calendar. “That’s right, it was just for our son’s birthday. His name is To because he was born on September 10 and the character 十 means ten. Also, around these days an exhibition of mine opened in the United States (A Poem of Perception)9, and it also has to do with the moon. Bunchi is from Hong Kong and the Autumn Festival is also celebrated there.”

B. “It’s one of my favorite festivals! I love paper lanterns with candles inside.”

Kenji is a big fan of the Czech conceptual artist Jiří Kovanda (1953–). In June 2019, by invitation of the Guimarães space in Vienna, Kenji Ide and Jiří Kovanda opened the exhibition YUGEN / Tsukimi10 . The show was curated by XYZ Collective11, consisting of Japanese artists who run a gallery of the same name in Tokyo.

The story of the exhibition and the full moon is as follows. A silent, darkened room, almost empty, is illuminated by Kenji’s work: two wall-mounted candleholders. In this night scene, a postcard with a raccoon gazing at the moon, stamped with a Czech stamp from the 1950s, rests on a window. It is an old postcard Kenji found in Japan. For him, the festival called Tsukimi (included in the title), which celebrates the autumn moon, is an opportunity for shy Japanese to share time with others “for no specific reason” and an excellent opportunity to invite Kovanda to share the exhibition hall. In response to this invitation—and in a minimal poetic gesture—Kovanda hangs a torch that projects a circle of light onto the ceiling of the room. The work was called Untitled (Looking at the moon)"12.

D. “I thought it was a romantic gesture that you could do an exhibition with this artist you admire.”

K. “Oh my god, you understand,” he says with a sympathetic tone and, laughing, he adds, “I think you are the first person who understands my exhibitions.”

D. “It’s a feeling I get when I see the photos of the room.”

It could be a contemporary scene from Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s In Praise of the Shadow. “The glow of candles flickering in the shadow,” he would say, and he would also recall, with humor and indignation, his two spoiled attempts to attend the full moon show almost a hundred years ago (the first ruined by the music and the second by the electric light)13.

K. “I think the people who saw the exhibition in Vienna couldn’t understand so much, there were some candleholders and the torch pointing to the ceiling, I think they were wondering “where is the exhibition?” he says laughing, putting himself in the visitor’s shoes.

D. “Are you still in touch with Jiří?”

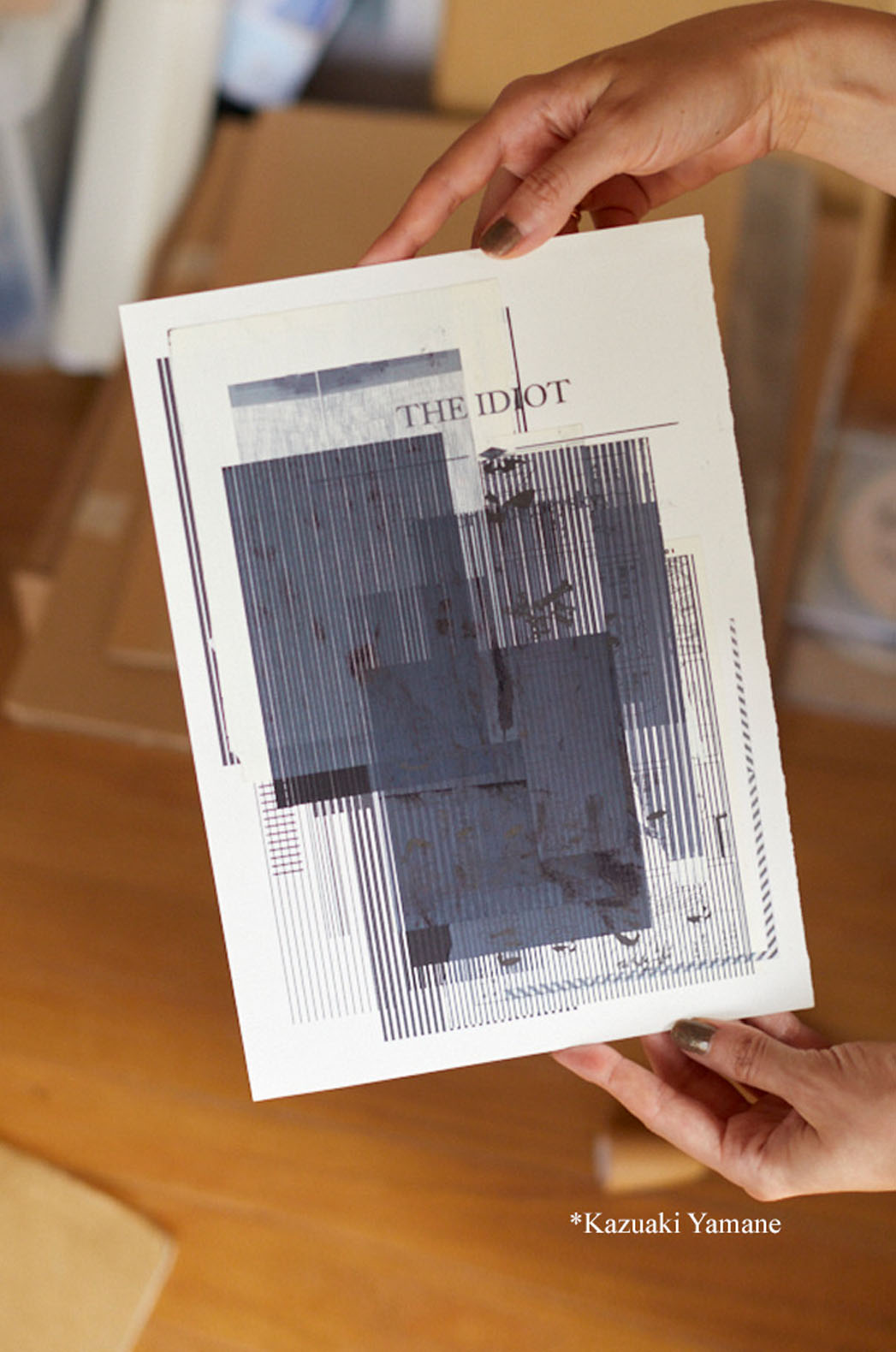

K. “Yes, after we met I sent letters to Jiří every year. He is very important to me. This is a bit of a secret project,” he says with a mysterious voice tone while looking for an envelope among his papers. After the experience in Vienna, I wanted to send him a thank you letter, or send him a card in the new year, that kind of tradition that in Japan is called nengajō,”14 he pronounces it with a didactic tone for me.

D. “Is it to wish a happy new year and good luck in the coming year?”

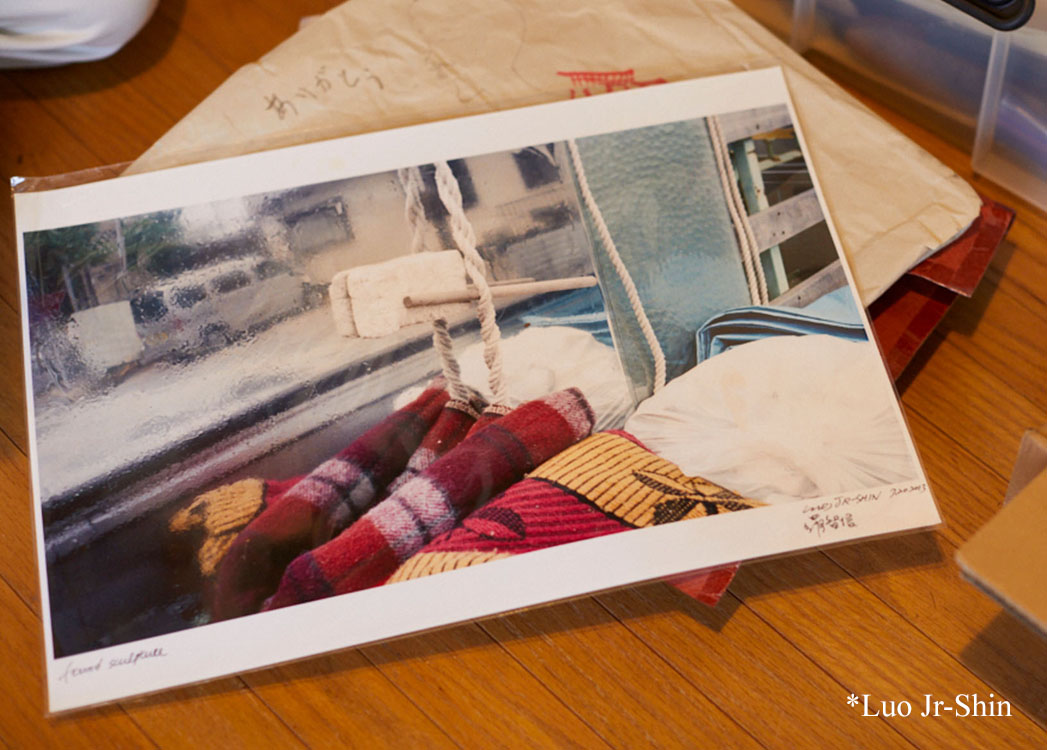

K. “Exactly, since we live far away and we can’t meet, I liked the idea of writing to him every year. And he answers me with this kind of thing,” he says holding his treasure.

D. “Is it a collage?”

K. “Yes, it makes me happy to think that the piece left a post office in the Czech Republic and made all that journey to get to Japan.”

D. “What did you send him?”

K. “I sent him an old postcard with a train that reminded me of one of his works, besides my son was fascinated with trains at that time. I have a picture somewhere.”

Kenji has the unique ability to interview himself. As if it were a guided tour of his home and his collection (in a way it is), he organizes the interview topics, generates the context for each story, even creates categories within his collection. He leads us to the studio and with a little bench in his hand, he starts:

K. “Maybe this is not strictly related to your project, but more than twenty years ago, when I was in the second year of high school, a teacher gave us an assignment: we students had to buy something in a gallery. But since we were very young we had no money. And at that time in the Ginza neighborhood there were galleries, but not as many as now. I went looking for something but I didn’t find anything, so I went into a second-hand store and bought this little bench.”

D. “So you showed up to class with this bench?”

K. “Yes, I think it was the first thing I bought as a ‘work of art,’ and I have been using it for more than twenty years.”

D. “What did your classmates bring?”

K. “One brought an iPhone, another the work of a street artist. I think the professor wanted us to focus on ‘how to recognize what a work of art is,’ on ‘how to buy art’.”

D. “I see.”

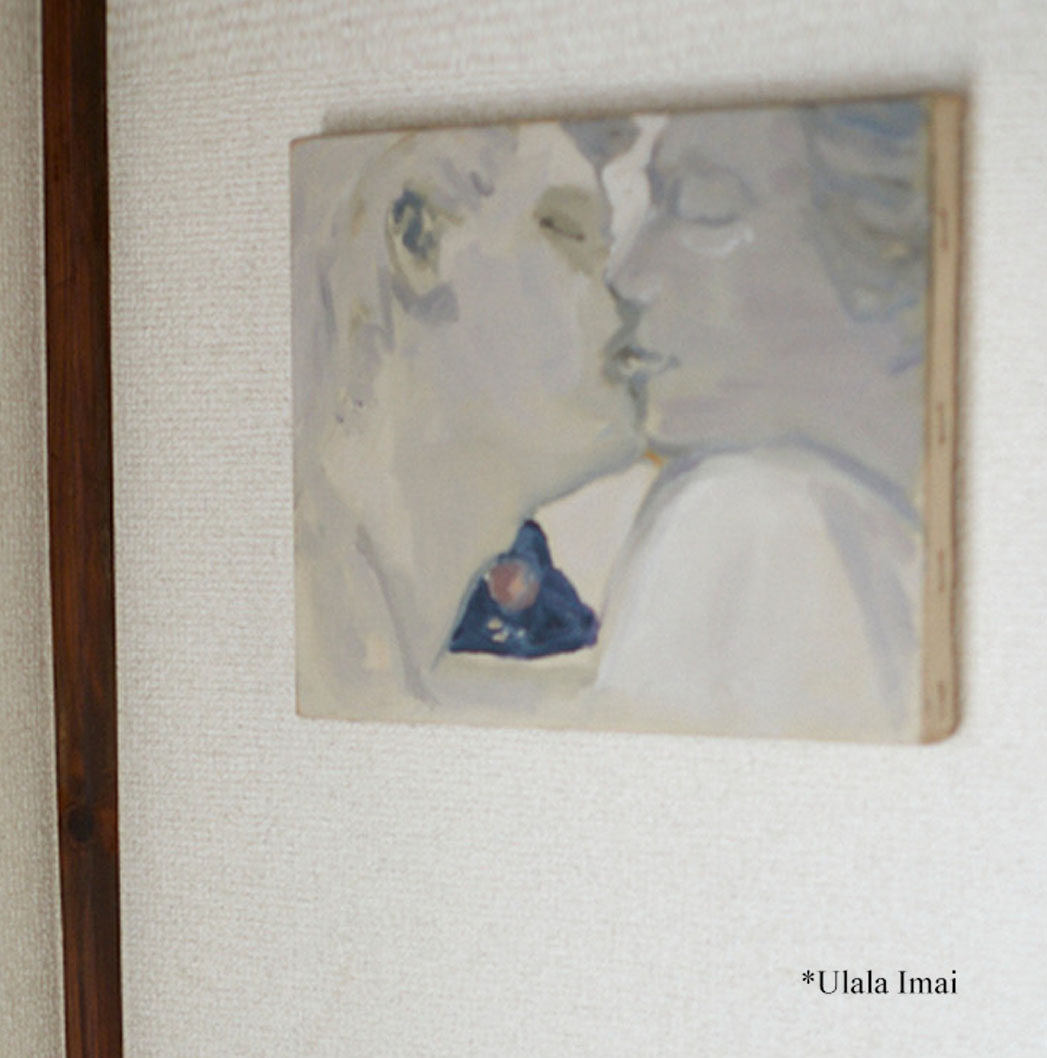

K. “The second work I had is this painting by the artist Ulala Imai (1982–)15,” he continues with the tour. “We were classmates at the university. I can’t tell you the price I paid (he jokes), but it was incredibly cheap, bah, secretly I can tell you, ha ha.”

D. “I guess it was cheap because she was still a student.”

K. “Right. I visited her at her studio, I liked the work and she told me, ‘You can have it, the price is up to you,’ so I said, ‘Ok, so, X yen,’ and I brought it with me, and I kept it all these years. Do you know her?”

M. “Not personally, but I know who she is.”

D. “Yes, she is quite famous now in Japan. I love her paintings.”

K. “This is her husband, Yu Nishimura (1982–)16, who was also a classmate of mine.”

M. “I took the photos for an interview with him, for an art magazine,” adds Marisa, who works as a photographer for different media.

K. “Oh yeah? This work is just from the exhibition before he became famous. The price was still friendly.”

D. “You have them together because they are a couple, ha ha.”

K. “They have three children now; they are very busy. He is one of my best friends. Besides, this was the first work I bought in Kayoko Yuki’s gallery (1980–), with whom I shared a house years ago.”

D. “Oh yes, what kind of gallery is it?”

K. “It is of the second generation of galleries, as we call it here. The artists they represent are my age, around forty. Maybe the youngest is in his thirties.”

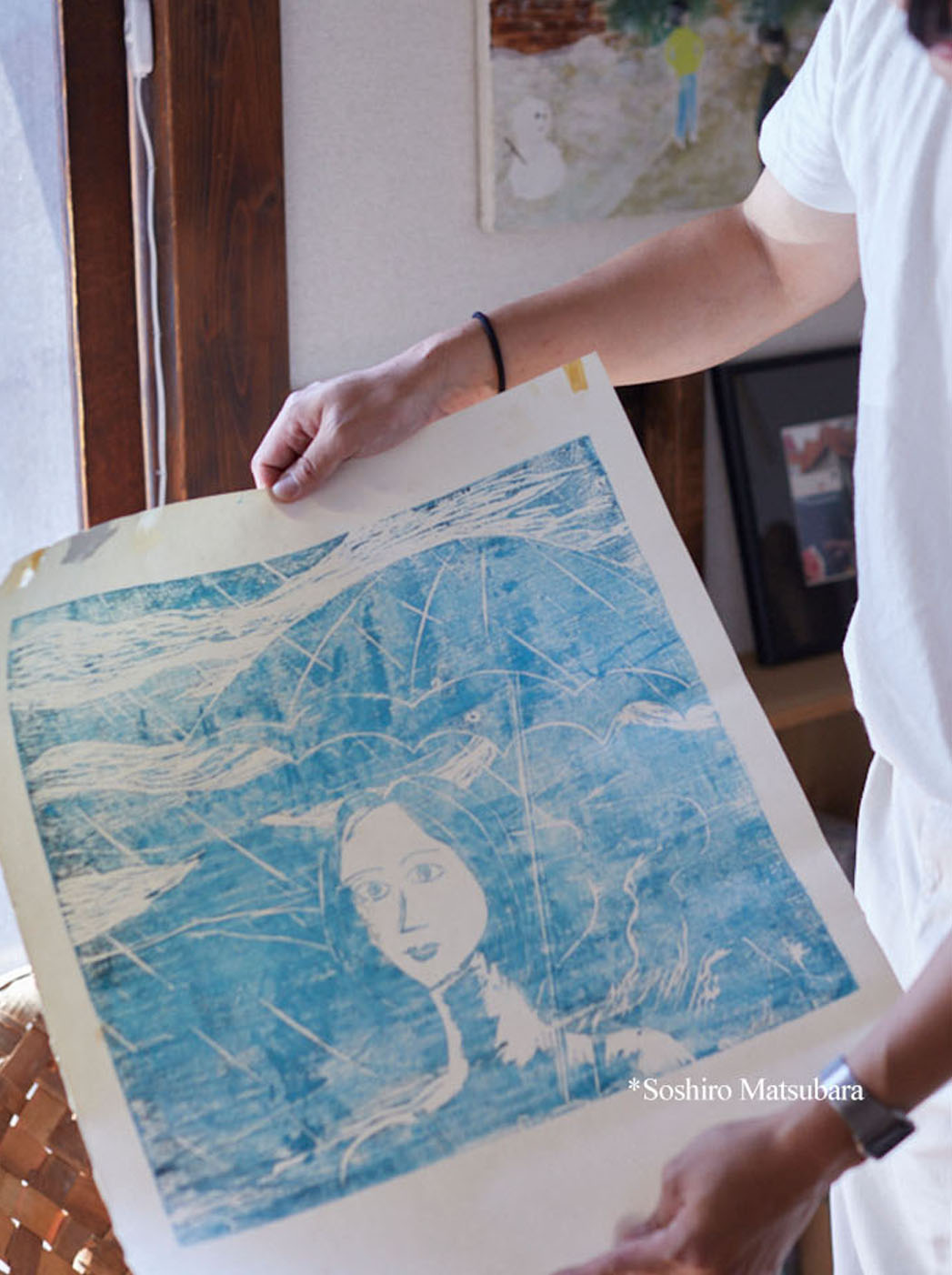

For four years Kenji shared a house in Machida, on the border between Tokyo and Kanagawa, with two people: the artist Soshiro Matsubara (1980–)17 and the current gallery director Kayoko Yuki18. In the evenings the house was filled with everyone’s friends.

K. “Each one came from different places. It was around the time of the 2011 earthquake disaster (and the Fukushima nuclear plant terrible accident). We hung out together a lot, it was like a fraternity. Masaya Chiba (1980)19 was walking around with a device to measure radiation, he would come to my bed and say: “Oh Kenji, your bed is not good, ha ha,” he says imitating his voice. “We shared a lot at that time and we were wondering: what is art? Soon Kayoko opened her gallery, it was like a catalyst. There are never enough spaces to show, so we had to do it ourselves. Just like the space XYZ Collective, which is formed by Cobra (1981–)20, who is an old friend from college. He was in a residency abroad, where there were many spaces run by artists, and that inspired him and brought him to Japan, then with other artist friends (Soshiro Matsubara and Futoshi Miyagi) they opened in 2011 a space in the Setagaya neighborhood (since 2016 it works in Sugamo).

D. “The galleries are a bit of a club, a meeting place… it’s true.”

K. “My generation was managed like that… I don’t trust the art scene, I believe in people and their creations. I’m not so interested in where those objects go, I’m more interested in the zero point of creation, the origin of it.”

D. “I understand.”

K. “One day Soshiro told us that he was leaving the house and so we helped him to empty it. But there was a lot of work, we both got excited and asked him if we could keep some things, and he said: ‘Yes, you can take them.’ I was the last one to leave the house. As you know I like to talk…”

D. “You have a great rhetorical capacity.”

B. “You express yourself very well.”

K. “Sorry, I’m talking too much.”

D. “We came here for that.”

B. “It’s ok, if it were just me, I’m shyer… we have very different personalities.”

Their son To comes to us smiling with the Pico Dulce I brought as a gift in his hand. The boy, with his straight black hair and bangs, is a carbon copy of his mother, and has a lot of his father’s personality. “Did you like the lollipop?” I ask him in English, even though he doesn’t understand me. He walks towards a Gatobus doll —the multiple-legged character from the animated movie My Neighbor Totoro— perched on the roof of a toy house, and with the cutest gesture in the world he offers the lollipop to the stuffed animal.

D. “Bunchi, how long have you been living in Japan?”

B. “Four years. I moved here when To was born.”

D. “And how did you meet?”

B. “I came to Japan for a month to do an artistic residency at Art Center Ongoing21. It was part of an exchange with another Hong Kong organization, Soundpocket’s Artist Support Programme.

K. “I went to see the show and I arrived at midnight, I had a drink, and Nozomu (Ogawa, the director) was also there, ha ha, and he introduced us. He said: ‘Kenji, this is Bunchi, from Hong Kong,’ and as he knows that I speak English, he said: ‘Talk!’ And we stayed talking all night. Then I invited her to a used bookstore in the Jimbochoo neighborhood that I wanted her to visit. It wasn’t love at first sight, but then I saw her exhibition and it was incredible, I wanted to have all the works.”

D. “Did you fall in love with her work first?”

K. “Yes, that’s what I was trying to explain. I started to collect her work,” he says, on the edge of laughter, “but economically it wasn’t very viable.”

D. “It was easier to share it with her.”

K. “Nozomu opened that space in 2008 because at that time if you wanted to do an exhibition you had to rent an expensive hall in Ginza, it was the only option. And he opened an opportunity for artists, the first five years he organized exhibitions in different places and then he opened the space in Kichijōji.”

D. “When I went to Ongoing I saw, in the book of its ten years, that you showed several times there.”

K. “We are very good friends with Nozomu and every two years he proposes to me to do an exhibition and I say: ‘Yes, why not?’”

As we move forward, the stories and the works multiply. They also push the limits of some categories, they move, they expand.

K. “I have different types of works in my collection, on the one hand those that I buy and, on the other hand, those that my friends give me as gifts. Well, and also some things that aren’t even artworks.”

D. “We are interested in that category too.”

K. “Sometimes I like a piece but I don’t have the money to buy it. For example, this one is by Ryoko Aoki (1973–)22, she is a drawer and one day she left this in my exhibition.”

D. “It fits into the archive category.”

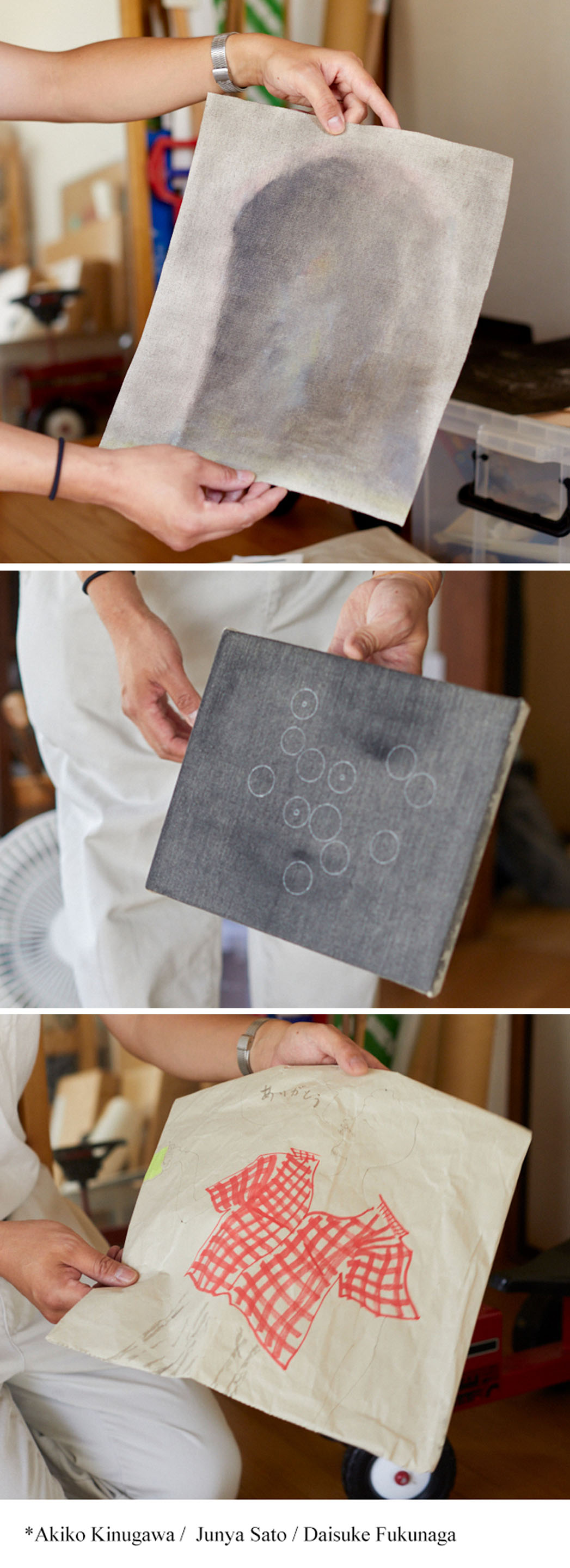

K. “For me it is a work of art. This other one is something that Soshiro Matsubara sent me, which Kovanda sent to him for me. I also keep the envelope in which it came to me.”

D. “What is the red stamp with squares on the envelopes for?”

M. “It’s for writing the zip code.”

K. “This is also Soshiro’s, although, for him, this is not a work. As I told you, we lived together and every time he drew on a piece of paper or something, I kept it secretly.”

M. “Like Akira Takaishi (1985–)23,” another artist we interviewed, friend of Kenji and husband of Maiko Jinush.

D. “Taking care of the works.”

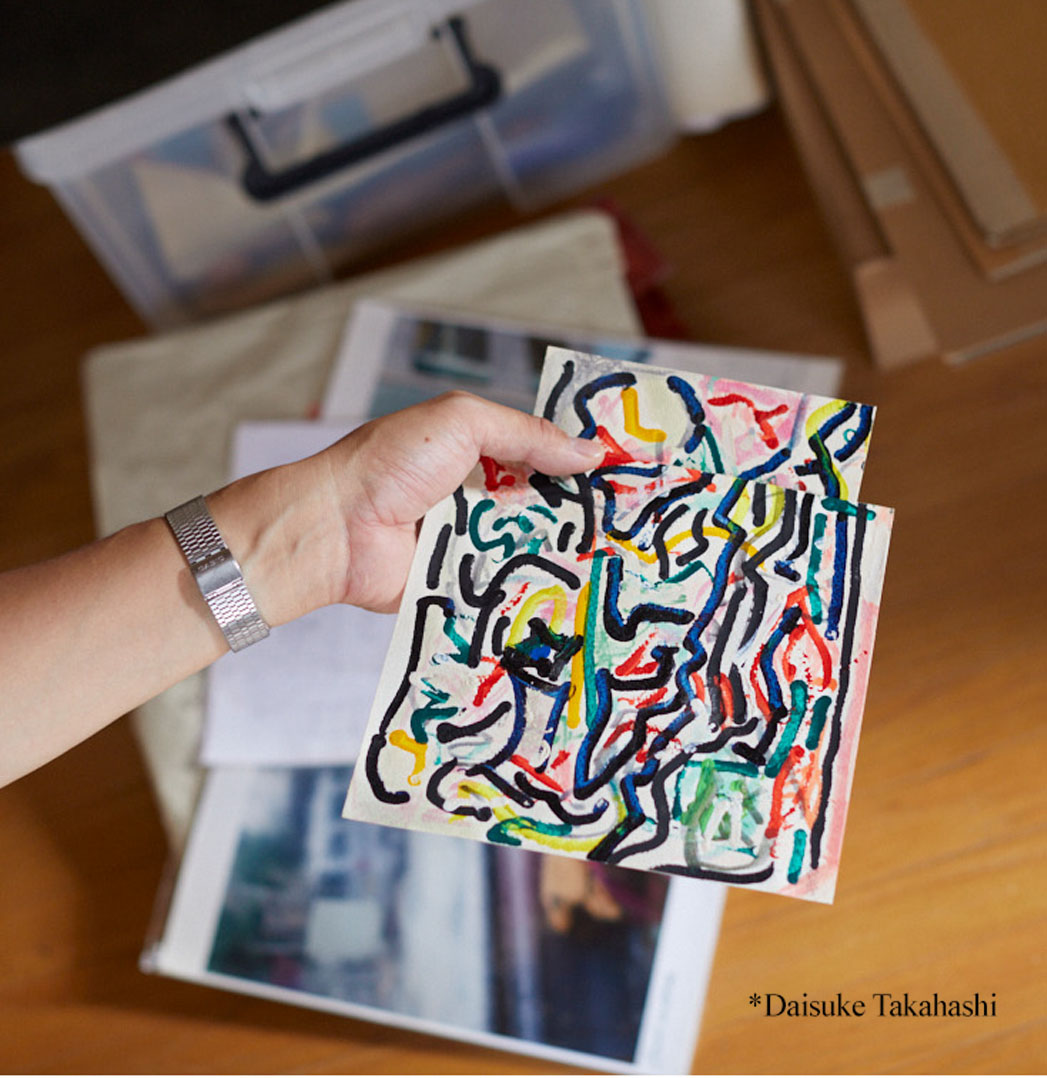

K. “This other one is by Daisuke Takahashii (1980–)24, who is also a painter. One day I visited his studio and I told him, ‘This piece is good, how much is it?’ and he answered, ‘It’s trash, you can keep it,’ ha ha.”

D. “It was a gift then.”

K. “Yes, from 2014.”

Perched on the wooden crossbeam, in a room that serves as a desk and studio, we found three small paintings by Bunchi. According to her website: “Her strong points are getting lost, collecting ‘natural objects’ produced by human beings and revealing the movement and dialogue under the surface to imagine the invisible thread of all things.”

Bunchi was born in Hong Kong or Xiānggǎng, which means “scented port.” I have been told before that being Hong Kongese is not exactly the same as being Chinese. After the First Opium War, in 1841 the British occupied the territory and only in 1997 (when Bunchi was 7 years old) did the island group return to the motherland as a Special Administrative Region. “Neither British nor Chinese,” Marisa summarizes,” Hong Kongese.”

She studied at the Academy of Visual Arts at Hong Kong Baptist University, but the habit of “picking up trash” (collecting) began during her residency program in Tokyo, and over the years she honed her efficiency—in a country obsessed with order and spotless streets. After disassembling, assembling, and combining these street treasures, new objects, artworks, are born. Her son’s toys, which are now part of her everyday landscape, also enter her production, and in her video Transition (2021), To’s favorite appears again: the train .25.

B. “This is a painting of mine that was used for the cover of a Hong Kong magazine. This other small work is a very early one, from when I was a high school student maybe. It is a self-portrait, it may even be the first one I did.”

D. “It’s beautiful.”

K. “I feel guilty now,” Kenji says apologetically,” I didn’t know it was from that time, I shouldn’t have touched anything then.” But Bunchi doesn’t seem to mind at all.

D. “I love your palette, Bunchi.”

K. “Me too.”

D. “You also did a show related to the illegal night markets in Hong Kong26."

K. “Yes, I copied the garbage and put together an installation. Hong Kong was my ideal city when I was a teenager, because of Wong Kar-wai’s films, and with Bunchi I had the opportunity to really get to know it.”

D. “And this little painting of a car?”

K. “It’s Bunchi’s too.”

B. “Ah yes, I made it as a farewell to the previous car we had, a Toyota that was fourteen years old.”

K. “We made an exhibition inside the car. We loved it very much, and it was its farewell.”

D. “Some people name their cars.”

B. “Sure, it is like another member of the family, and it was retiring. I took some of the green color of the car and made this work as a tribute.”

K. “She did it like a funerary object.”

Several friends attended the farewell. The group show was called Sayonara Mark II, Toyota Mark II (2021), and the artists who participated were Masaya Chiba, Hanayo, Reiji Saito, Yuya Koyama, Daisuke Fukunaga, Kenji, and Bunchi.

According to an ancient Japanese belief, when any everyday object reaches one hundred years of age, it is possessed by a spirit and comes to life (Tsukumogami or “spirit artifact”). According to the treatment they have received, they will become benign or malignant beings. If they were abandoned on the street, then they will take revenge. To avoid being pursued by one of these beings, for New Year a big cleaning is organized and the objects are thanked before being discarded, some guilds even prepare funeral rituals to say goodbye to their work tools and recognize their service. After all, for Shinto27, all objects of nature and man-made objects possess a spirit.

“In every corner you can find a god,” Kenji will say. In another work—a letter placed on the sun visor of the old Toyota—Bunchi dialogues with another kind of ghost. It reads:

Dear Kenji´s every ex-girlfriends,

Hi, I'm Kenji´s last girlfriend in Mark II.

Second seat is warm, even I was slept

and had a dream. Didn't you feel so?

Sincerely, Bunchi, 2021.

In the corridor there are some works linked to his son To:

K. “This is a photo by the photographer Hanayo (1970–)28.”

D. “The costume that To has in the photo is interesting. What is it about?”

B. “It is a traditional Japanese outfit…”

K. “Well, she is interested in the old style, and she tried some things and that’s what it is. And this other work is by Maki Katayama (1982–)29, Masaya Chiba’s wife, who is also a painter. It was a gift for To’s birth.”

D. “Oh, he has his collection then too.”

K. “Yes, it is a sort of commemorative calendar with our wedding dates and the birth of our son.”

D. “And this drawing?”

B. “Ah, I did it for To’s birthday last week.”

D. “And what is this that reads Toto forming a face next to the clock?”

B. “Oh, that was a gift from a friend, because our son’s name is spelled To and he just found this vinyl and gave it to us (Turn black from 1981, the third album of the American band Toto).”

K. “We haven’t listened to it yet, ha ha.”

B. “I think we did listen to it. But the cover art is much better than the music as I remember, ha ha ha —I confirm. We also have this photo that Hanayo took of us, it is a family portrait of one of the times he came to our house, in fact it was taken in this very place.”

D. “This corner is beautiful.”

M. “Even the hula hoop on the palm tree looks like a work of art, ha ha.”

D. “Everything can be art in this house, ha ha.”

K. “Sorry for the messiness of this story.”

D. “Lots of stories! Don’t worry, that’s how our interviews are.”

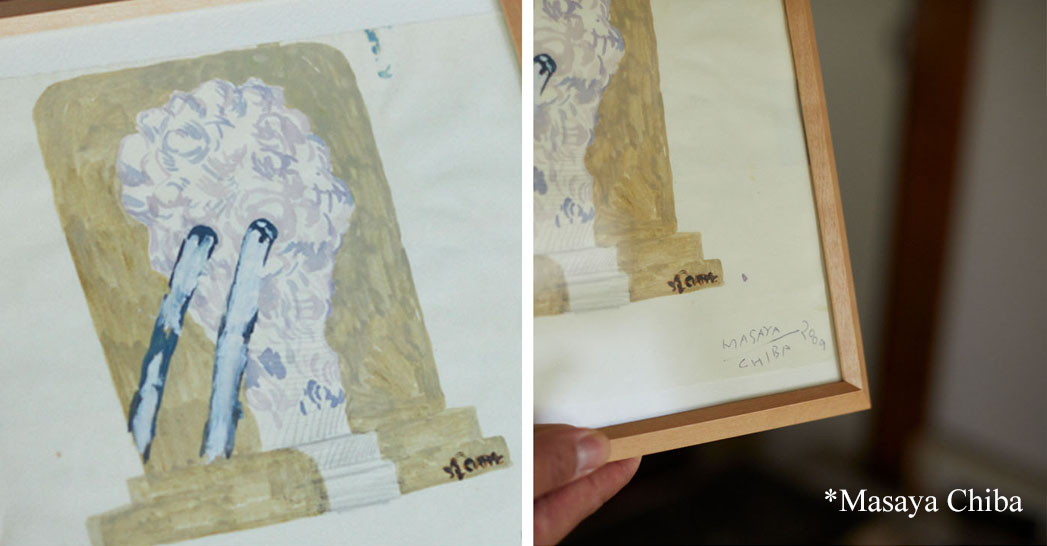

K. “This is a work by Masaya Chiba, maybe you know him.”

D. “Yes, of course —it is also the fourth time his name appears in the interview.”

K. “He is a very good friend of ours, and he is also a very good collector,” —he says, emphasizing this last part.

D. “Was it a gift?”

K. “Maybe… ha ha, I am not sure. I have several works by Masaya Chiba, the story of this one is that one day he called me and asked me to come to his house, I told him I was tired, then he said, “Please, if you come I’ll give you a work, I’ll even paint it right now,” he says imitating his voice. “He needed me to take him somewhere with the car. [Laughs.] These other works I have of his were from some moving. His house was a chaos, sorry to say it but it was almost a garbage dump, ha ha.”

D. “Akira (Takaishi, another interviewee) told us the same story.”

K. “I asked him, ‘Masaya, do you need this one?’ ‘and this one?’ And he would answer, ‘Take it’.” He laughs as he remembers the moment and, imitating his friend’s voice, he adds: “Every now and then he would answer, ‘This one is important, but you can take it with you.’”

Masaya Chiba is one of the most promising painters of his generation and is a professor at Musashino and Tama Art Universities. In 2021 he had a rather impressive solo exhibition at Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery30, a large installation in which his turtle walked along a platform that crossed the room surrounded by paintings (in which he was also depicted), while his gait was captured by small cameras and could be seen from a QR code.

From a small door high up in the desk area, more works emerge. Gallery purchases, direct purchases in the workshop, discounts and friendly prices, gifts, thanks for favors, cleaning, souvenirs, confusions. And with them, the first stories of exchanges appear, which are not so common among the Japanese artists we interviewed, at least compared to the stories from Argentina and the famous local barter.”

K. “Masaya came to my studio one day and asked me for a work, so we made an exchange. I gave him one and he gave me this drawing. It was an unequal exchange because the prices are very different, my work costs much less than his.”

D. “Well, but you are friends…”

K. “Yes. We never hung it, Bunchi says it is a very strong image for our son.”

B. “When To was a baby I was impressed by the fact that he saw the dead person,” she laughs, and we all do, “now it’s fine, but when he was a newborn it seemed strange to me.”

D. “Let’s pretend he is sleeping, ha ha. You have a big collection of works.”

K. “Yes, I think so.”

D. “Bunchi, do you also have a collection?”

B. “Yes, but I don’t have so many works. I’m poorer,” she jokes.

K. “Well, I didn’t buy all these works either, ha ha. I did buy this one for example,” he says while unpacking a portrait.

D. “When you buy a work, does it come in a custom-made box?”

K. “So, so, so, so…”

Kasaki Amane’s work appears, inspired by a Japanese manga, Baka Dou, which literally means “Stupid idiot”. “He came to my studio and told me he liked my work, so I told him, ‘Ok, let’s exchange.’”

D. “Is the exchange of works between artists a usual thing?”

K. “It was more like a robbery; I said, ‘I’ll take it.’” His laughter is a bit theatrical and contagious.

He continues to take packed things out of the little wooden door hidden at the top of the studio. Another black work with white circles appears. It is by Junya Sato (1977–)31, a conceptual painter who in this series, called Cash Flow, paints what he finds in his pocket when he arrives home. A portrait of the contents of his pocket.

D. “Did you buy it?”

K. “Yes, I bought it directly from him, not at the gallery,” nervous laughter, “I asked him what the price was and I paid what he told me.”

D. “I was wondering how this kind of arrangement worked here.”

K. “The gallery he works with is not so sensitive with this kind of thing.”

D. “Sure, I guess it’s not the same to sell to an artist friend as it is to a collector. It’s something that stays between friends.”

K. “Yes, exactly.”

D. “Do you consider you have an art collection?”

K. “Yes, I do”

D. “Maiko (Jinushi), for example, told us when we interviewed her that it was only when I contacted her about the project that she became aware of having a collection, that before that she hadn’t thought about it.”

K. “More than an art collection, I think that what I have is my collection. Works that have to do with my memories, with my friendships, works that I have because they inspire me… I don’t know, maybe when Jiří is gone… and I have this work…”

B. “I have many artist friends, although I don’t have many works by colleagues. When I met Kenji and saw his collection I started to think that I could also buy works, but I don’t have money.”

D. “But artists as work producers have the advantage of being able to exchange their works with other artists.”

K. “That is not usual here.”

D. “Why do you think that is, do you think it is not a fair exchange?”

K. “Maybe, I think it has to do with the fact that if I like someone else’s work, I don’t want them to feel obliged to have one of mine.”

D. “Don’t you think that maybe the other person might also like your work?”

K. “Yes, maybe, sometimes I have exchanged works, but I can’t be sure. I don’t know what this is. Maybe I bought it somewhere. Sorry, I’ll check it later.” [Laughs.]

>>>>“This is another part of my collection, I have these works because they inspire me. The artist’s name is Kohei Kobayashi (1974–)32, and the work is titled What are you going to do? We are not friends, that is, we know each other, but I bought it because it inspires me.”

D. “In the interviews in Argentina, the artists talk about this kind of links with the works in their collection.”

K. “I need some works close to me. He made more than a hundred of this kind of drawings for this exhibition and I loved them, and I bought it as a memory of that moment.”

At the beginning of the twentieth century, when he was five years old, the famous anthropologist Lévi-Strauss built a dollhouse with a box. From the terrace you could see a Hiroshige landscape, a gift from his father, a painter who, like many impressionists of the time, collected Japanese Ukiyo-eprints. Over time, the little house was inhabited with miniature furniture and Japanese-made characters bought from the Rue des Petits-Champs in Paris33.

D. “I wanted to ask you about your experience as curator of Sylvanian Gallery.”

K. “Yes, it was an invitation to several artists to do a group show in miniature, using the Sylvanian Families34 houses as an exhibition space. The works had to be miniatures of works that exist in real life.”

D. “I don’t have any dolls, but every time I see them I want to buy them.”

M. “We have one at home too.”

K. “I always played with houses and furniture, but not with dolls. In the studio I have some houses and catalogs, I’ll show them to you later.”

Artists are invited to curate a miniature show using the dolls’ home as a location. An imaginary collection? Sylvanian Gallery began on Instagram in 2016 and materialized into two exhibitions. The first was called Sylvanian Families Biennial (XYZ Collective, 2017)35. If we bend down to look inside the little house chosen by Masanao Hirayama (1976–)36 we see a mini projection. The artist recreates—with a plush teddy bear—Steve McQueen’s award-winning video Deanpan (1997), which in turn reinterprets a famous sequence from Buster Keaton’s 1920s silent films, in which the facade of a house falls on McQueen himself, who is unharmed because he is standing right in the window opening.

Twelve artists and one collective participated: Yosuke Bandai, Masaya Chiba, Masanao Hirayama, Kenji Ide, Kei Imazu, Hirofumi Isoya, Tatsuo Majima, FM (Daisuke Fukunaga & Soshiro Matsubara), Hikari Ono, Ryohei Usui, Yui Usui, Masahiro Wada, Workstation.

A few years later, in 2020, Welcome to Sylvanian Gallery37 was held in the Utrecht bookstore and art space, hidden in a small street in Omotesando. Some iconic works of contemporary art coexist between the three plastic walls of the cottages. Prada Marfa by Elmgreen & Dragset shares the building with the (more Asian) work of Félix González Torres: Untitled (fortune cookie corner) in the version that Yu Araki (1985–)38 entitled Good Deeds. Some works by two Japanese legends of the sixties like Yoko Ono (Cut Piece, 1965) and Genpei Akasegawa (Canned universe, 1964) also appear; and Kenji takes the pleasure of recreating, with a rat and a rabbit, the work Kiss through Glass (2007) by the beloved (and already mentioned) Jiří Kovanda. In this second edition participated the artists Ryoko Aoki, Yui Usui, Masanao Hirayama, Yu Araki, Zon Ito, Yuichiro Tamura and Ide himself.

Traditionally, Japanese houses have a “public” side, limited to the rooms facing the street, and a “private” side, reserved for domestic life inside the house. “To what point a guest penetrates the house depends on his or her relationship to the family.” The Japanese word for “interior” or the “deepest part” is oku, hence wife is said oku-san, “the lady who inhabits the depths of the house.”39

As we are talking in the kitchen, which, a few months ago functioned as an exhibition room, Kenji asks me:

K. “Do you remember the exhibition A Day of a Housewife in which the artist Mako Idemitsu (1940–)40 participated? She is a Japanese artist from the sixties, who makes cinema and video…”

D. “Yes, I remember (he refers to an exchange we had on Instagram), a feminist artist, who as a young woman went to live in the United States.”

K. “Yes, now she is living in Japan again.”

A Day of a Housewife was a small (and curious) exhibition that took place in the kitchen of this very house and lasted only one day, Saturday, January 15, 2022, at lunchtime. The three artists who participated were Yui Usui (1980–)41, Bunchi (our hostess), and the famous Mako Idemitsu, who showed her 1977 video A Day in the Life of a Housewife. On her website she remembers: “This video was shot in those days when I was really fed up with being a housewife. In the endless repetition of routine household chores, I realized that another “I” was watching the housewife’s “I.” Who am I? What is living? I wanted to share these questions with others.”42.

To better situate Mako Idemitsu, let’s remember the famous Feminist Art Program of CalArts (California Institute of the Arts) organized by artists Judy Chicago (1939–) and Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015) in 1971. During the women’s liberation movement, Mako Idemitsu, who was living in California at the time, filmed Womanhouse (1972), her first film work in 16 mm, showing the environments of the old Los Angeles ramshackle mansion transformed into Womanhouse. As part of the exhibition, Miriam Schapiro exhibited her work Dollhouse (1972),43 subverting with humor the saying “A woman’s place is in the home.”

K. “This is a collection of her works,” he says, holding some Idemitsu DVDs. “They are very cheap too, 3,000 yen (21 dollars) each, because she doesn’t really care about the price.”

D. “Thank you for showing us this material, you are very good collectors.”

K. “Very messy too.”

In the background of the audios you can hear little To chanting for attention; by his melody, he is perhaps playing at copying the sounds of his fire truck. During the interview, imitating his father, To quietly unfolded his own collection of books, papering the living room tatami with them.

D. “How old is To?” He goes ahead and answers me directly, making the number four with his fingers. “I didn’t know he spoke English!”

K. “It’s just that we speak English between us and he wants to understand, so he is learning. He speaks Japanese, a little bit of Cantonese and some of our English which is not perfect, I feel sorry for him, ha ha.”

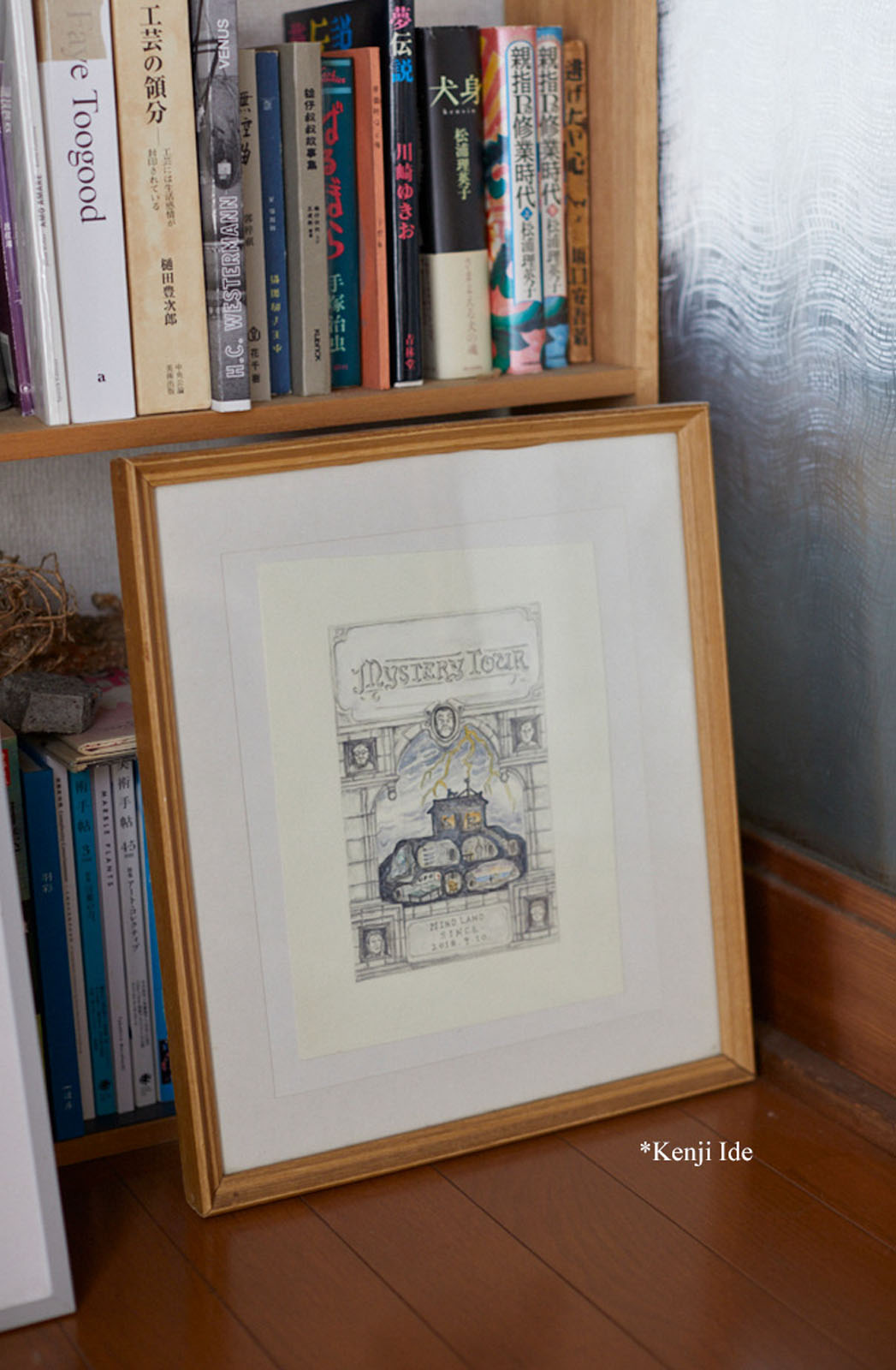

D. “What about this drawing, Mistery Tour?”

K. “Ahhh, that is a work I did for my son, it is also linked to Masaya Chiba. He has a project called Tree Gallery which is basically to show in a tree. In front of his studio there is a big tree and every year, when he does an Open Studio, he invites some artist to show there. Sorry, my stories are always long,” he says with a laugh. “It was part of a project called Alpha M44 at Musashino Art University. I told him that my son was about to be born and I wanted to do an exhibition just for him.” “Such a selfish idea,” he adds, and we all laugh, “but he loved the idea, so we did it. And I did this work for the show.”

D. “Didn’t you both participate?”

B. “Yes, the show was called Hello Baby. I used my favorite clothes to make clothes for the baby, which hanged between the two trees. The idea was to celebrate his arrival to this world.”

D. “To is a very lucky child.”

K. “The drawing is based on a Disneyland attraction from my childhood, which was in Cinderella’s castle. I loved the site map, and it was inspired by that.”

D. “Your studio, Tana Studio, also participates in these Open Studios, doesn’t it? I would like to visit the place.”

K. “Oh yes, of course, come! I have works from my collection there too.” [Lots of laughs.] Our friend Maki Katayama invented the name Super Open Studio (S.O.S)45.

Around noon we sat down to talk. In the tatami rooms, life takes place at ground level. When it is available, the furniture is small and low. On a small wooden table, which looks like a toy, tea is served in ceramic cups, and we try some traditional Japanese sweets with nuts that I brought as a gift—which inconveniently stick to our molars.

D. “I was wondering if you can make a living from art in Japan, or do you need a second job?”

K. “You definitely have to have another job.”

D. “In Argentina it’s quite difficult, very few artists make it, I thought that in Japan maybe the conditions were more propitious…”

B. “In Japan it is more difficult than in Hong Kong I think, here there are many more artists, and the prices are lower than in China.”

K. “There is more competition too.”

M. “I think the art market is much bigger there.”

D. “In the important international auctions you see many Chinese artists, and Japanese artists not so many… except Takashi Murakami (1963–)46 and Yoshitomo Nara (1959–)47.”

K. “That’s true, except for… Murakami and Nara. I think the art system in Japan is also very strict, what is art and what is not is more regulated. Here, little by little, something is beginning to change; for example, artists are opening their own spaces to sell their works, or working in ceramics to have other income.”

D. “In the Artists’ Collections book we interviewed Irana Douer, an artist who had an art gallery for several years, and who recently opened a store @id.lb that sells objects made by artists to a wider public and at accessible prices.”

K. “I think that this is starting to happen here too, that artists are looking for other ways. When I was in Indonesia ten years ago, I understood that for them it is different, everything is art, a t-shirt, a handicraft, they think differently. Economically they don’t have everything solved, but they are not asking themselves what contemporary art is.”

D. “Maiko, in her interview, said the same thing, that everything they do in Indonesia is part of their artistic practice; she told us about her residence in Kunci48 in Yogyakarta. On the opposite extreme, I come from the Western tradition, where the difference between what is considered fine arts and crafts is very big, and it strikes me that in Japan, for example, there are so many galleries that sell ceramic objects at the same level as art galleries. When you Google ‘Art Gallery Japan,’ many galleries selling ceramic objects appear.”

K. “Sure. Here everything is very delimited, there are those who work with contemporary art, those who work with handicrafts, those who work in the Asian market of objects… there is no fluid dialogue, we speak different languages. I think that when we can set foot outside those limits it will be more interesting. And that has not happened, at least not yet.”

D. “I think that in the West that border is very clear. I understand that in Japan the term Bijutsu49 (Fine Arts) was born only at the end of the 19th century, much later than in Europe, for example.”

K. “Of course, compared to Europe it is very different.”

D. “You have some ceramic objects in the kitchen, can we see them?”

K. “Pottery is also a work of art. These are from Okinawa. I don’t collect ceramics,” he clarifies immediately, and emphasizes the following sentence, “because there are incredible collections, and in Japan there is this whole popular art movement called Mingei (popular handicrafts).”

D. “Yes, there is the Mingeikan (Japan Folk Art Museum)50.”

K. “It is the best museum you can visit.”

“I have reached a point where I cannot spend a single day of my life apart from the world of beauty,” writes in 1925 the passionate and categorical Soetsu Yanagi, creator of the term Mingei, founder and main theoretician of the folk crafts movement in Japan. And in a later writing he tells how the term came about: “We took the word min, meaning ‘the people’ or ‘the masses,’ and the word gei, ‘crafts,’ and combined them to create Mingei51—literally, ‘people’s crafts’—in order to designate the ordinary objects that ordinary people use in their daily lives and to distinguish them from the objects of the more aristocratic fine arts.”

Yanagi and his colleagues, after spending several years touring Nihon, visiting artisans and building up a collection of folk crafts of about 17,000 pieces, succeeded in creating a museum to honor the lives of the common people of their country: “Like a Buddhist monk who decides to follow the path of religion, we decided to devote ourselves to the promotion of folk crafts.”

K. “This kind of Okinawan pottery that has drawings on it is quite special, the artist is called Jirō Kinjō (1912–2004)52—in 1985 he was the first person from Okinawa to become a Living National Treasure. It was made many years ago. The price of pottery in Okinawa is super cheap.”

D. “Next week I am going to visit Tokoname City, a very important pottery production center in Aichi prefecture.”

K. “Oh yes, very important,” he says as he slides the door of the crockery cabinet and takes out other pieces. “This is from another important center in Aichi called Seto.”

Sotomono is the generic term used to refer to pottery, evidence of Seto’s importance as a production center. Located twenty-five kilometers northeast of the city of Nagoya, Seto is best known as one of the Nihon Rokkoyo (the six oldest pottery centers in Japan), which are: Shigaraki (Shiga prefecture), Tanba (Hyogo prefecture), Echizen (Fukui prefecture), Bizen (Okayama prefecture), Tokoname and Seto (both in Aichi prefecture). Known as the Six Ancient Kilns, these pottery production areas with their distinctive pottery cultures date back from medieval times, and were recognized as a Heritage of Japan in 2017.

To make the limits of the categories of art a little more complex and blurred, other pieces appear.

K. “I didn’t buy these works in a gallery, but in a second-hand, vintage store. They also make me wonder where the limit is between contemporary art and what is not. This is from my favorite store in the neighborhood, Nishi Ogikubo53. It sometimes sells art pieces or curates exhibitions, but it doesn’t work as a gallery, its owner doesn’t consider herself an artist, she’s not thinking about those things.”

D. “I understand, there are different ways to be an artist.”

K. “For example, this was the first exhibition of this photographer in my friend’s store. Yet the photos were not sold, but a more accessible inkjet copy. Most of the works in my collection are works by artist friends, from the contemporary art scene, but I also like when I find, or Bunchi finds, this kind of things that we come across in the street. That looks a bit like contemporary art, and that leads us to ask ourselves that kind of question.”

D. “And these strange objects that look like stones?”

B. “I gave it to Kenji for his birthday. I think it’s an object from the sea coast, but we don’t know.”

B. “I think it is man-made, but it was eroded by nature, I like that concept and that transformation that turns it into something else.”

In the Instagram account of the store @poubelle0702, a series of objects float on a very white background. With an impeccable curatorship—the opposite of a flea market—they sell: a fragment of an antique sculpture (the toes of a foot), a wooden toy truck from another time, bottles, books and art posters, a metal bowl with traces of use, dishes restored with the kintsugi technique, three curious shaving brushes, a rusty abacus, boxes and little boxes with particular designs and shapes.

B. “That store is my hobby.”

K. “The owner has an idea of art, but what she chooses are vintage objects, with an aesthetic sense that we love.”

D. “She has a good eye for choosing objects.”

K. “Yes.”

That week I wrote to Maiko to tell her that Kenji had invited me to visit his studio and that he had managed to find a space in Masaya Chiba’s schedule so that we could visit the studio he shares with his wife Maki Katayama. She replied: “How nice! I’m really glad about this coincidence: you found me and Masaya through another way, I introduced you to Kenji, and now he’s going to take you to meet Masaya. It’s like a novel, isn’t it? ha ha. I feel like we have an instinct to find friends and I feel like the world is still small. That feeling makes me happy.”

The city of Sagamihara brings together living and working more than a hundred artists, generally from nearby universities (Joshibi Art and Design, Tama Art University, J. F. Oberlin University and Tokyo Zokei University). The area of empty warehouses, former factories, former mechanical workshops, former garages for dump trucks or even a gardener’s office in a gardeners’ area, is ideal for artistic work because they are available, cheap and suitable for dirty and noisy tasks (except in winter when weather conditions can make them a bit hostile, I can attest that in summer as well).

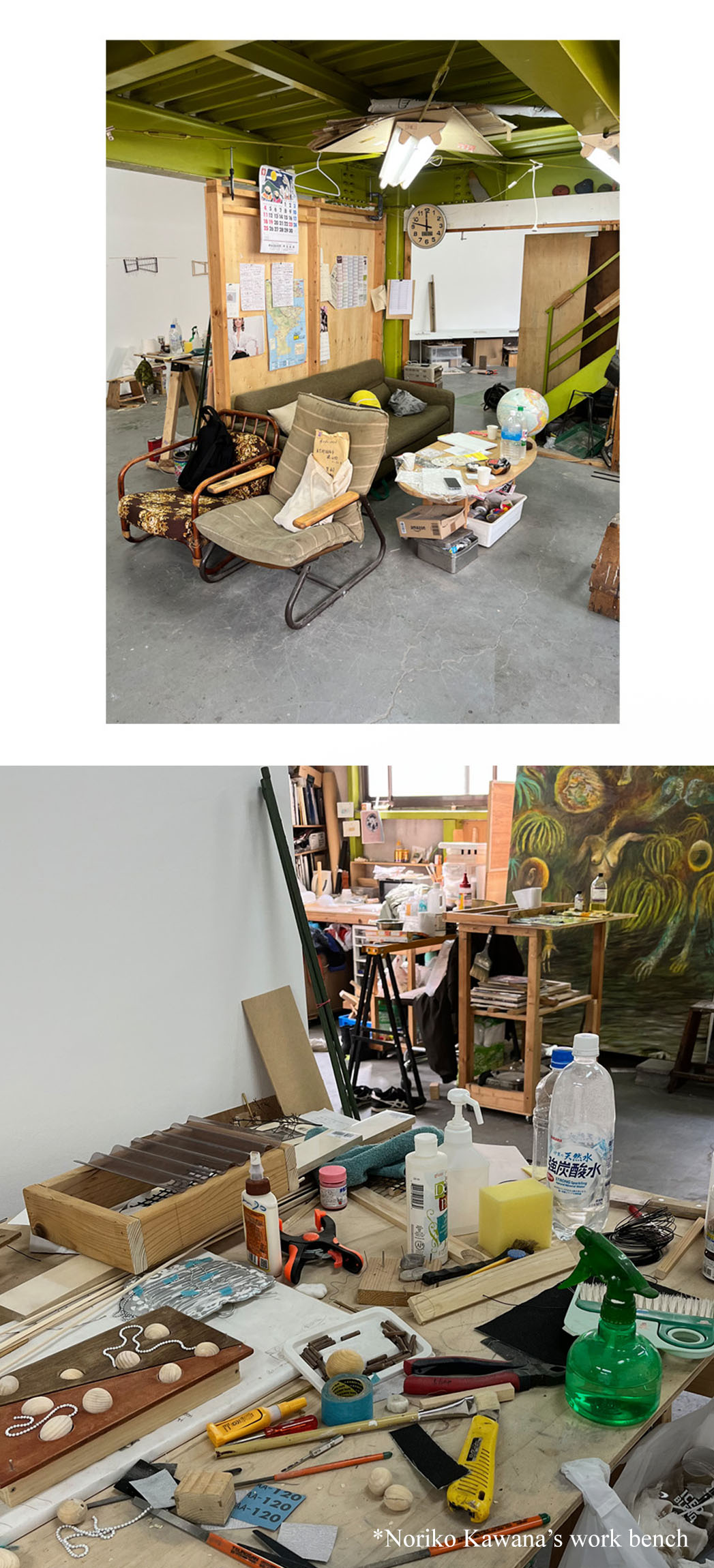

Ten days after the interview Kenji drove me to see his place at Tana Studio. Back then there were seven artists working there, but now there are only three: Taichi Nakamura (1982-)54, Noriko Kawana55 and Kenji. “I have been working here since 2006, after so many years I have an almost family relationship with the owner of the factory who is now retiring.”

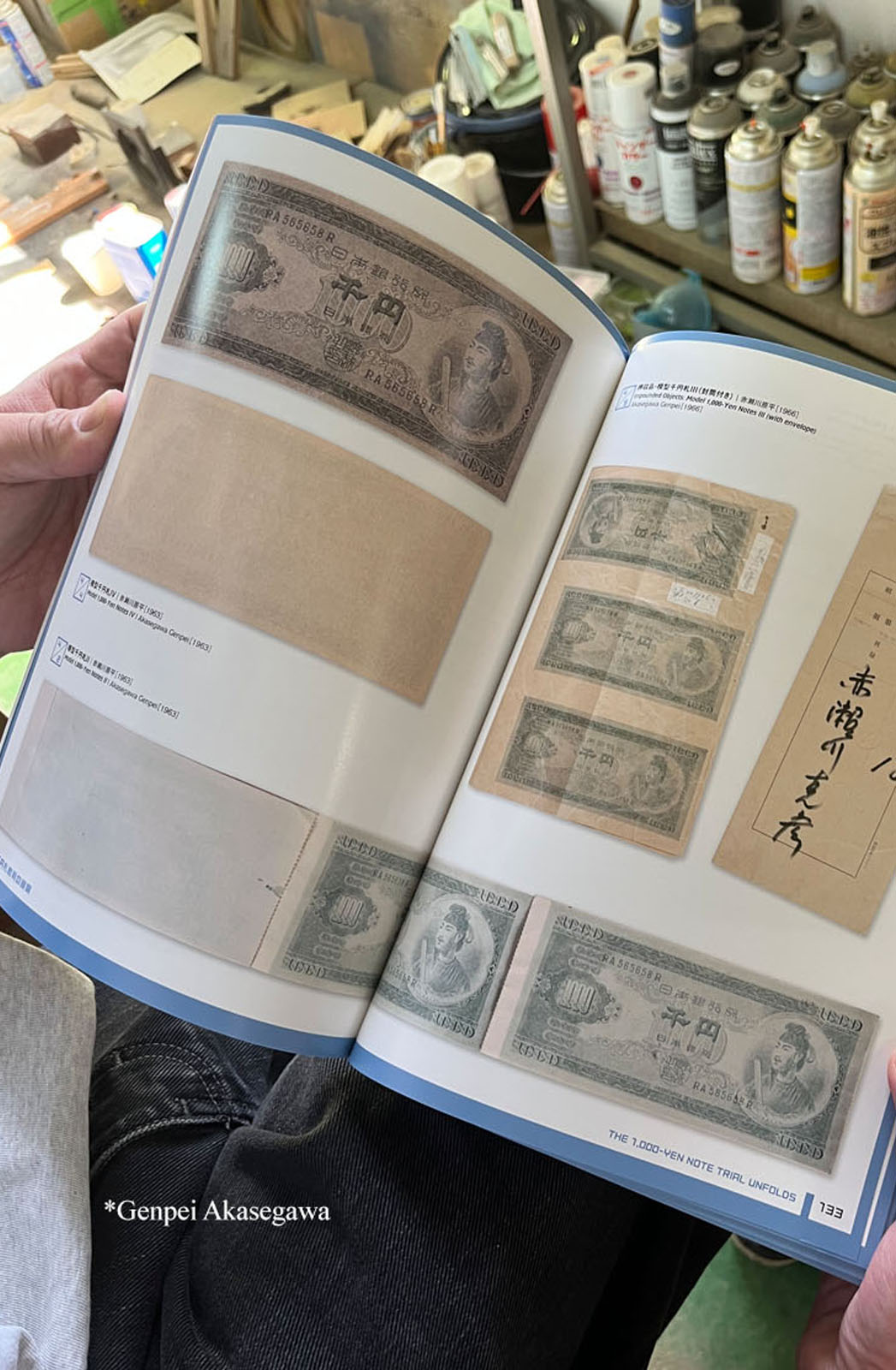

In front of the studio library —which he likes to call “public library”— a mini-class on Japanese art history of the 20th century took place. We stop at a book by the legendary Genpei Akasegawa (1937–2014)56, imprisoned for counterfeiting thousand-yen bills, and he tells me about his participation in the radical collective Hi-Red Center (Haireddo Sentā) and their actions in public space in the early 1960s. While he lights a cigarette, we listen to some Japanese rap: Nazoraz.

K. “One day Masaya came, in 2007 or so, I had a friend who became very famous doing hip hop and he told me: “Let’s give it a try.” We didn’t have any skills, we didn’t know anything about rap or music. We made music for fun for a few years, we recorded a CD, we didn’t sell it, nobody bought it, we gave it to friends, and we made this book with the lyrics. There are a lot of bad words, don’t look at it closely, ha ha. Maiko appears too… look at the credits.”

D. “Here she is, Jinushi-chan. Oh yeah, she works with drummers in some of her videos.”

K. “Yes, she has a band.”

D. “I don’t see your name on the list.”

K. “I used a pseudonym, but I can’t say it while recording, ha ha.”

D. “It sounds like a pretty professional recording, and it also sounds like you were having fun.”

Once a year, in November, the Super Open Studio (S.O.S.) takes place. Twenty or so artists’ studios in the area open to the public, in addition to organizing artist-curated exhibitions, workshops, events, talks (there’s even a shuttle bus that connects the studios and offers guided tours). Kenji was co-founder of the movement, part of the organizing committee and guide until a few years ago, when he “gave way to the younger generations.”

M. “Who attends, do more students or collectors come?”

K. “Mostly people who visit exhibitions on a regular basis. Some collectors at the beginning, but not so much anymore. Also artists who want to come to the workshops and come to visit the places because they are interested in renting. I sometimes did exhibitions, invited younger artists to show for a day, to do some projections. In fact, many of the artists that represent XYZ Collective came from here… Koji Nakano (1977-)57, Hikari Ono (1990-)58… but what interests me most is the exchange with other artists, that things happen here, within the art community.”

Before ending the interview, I ask him about his work. Kenji can be very extroverted, but he suddenly becomes shy when it comes to talking about his own production, his private world, his processes. Of the child who spent his afternoons playing on the shores of Kaneda Bay, or of the young student who used to get lost in the vegetation surrounding the university and who no longer exists.

D. “You used to make bigger works, like installations, didn’t you?”

K. “Yes, I used to make bigger works, but just before the birth of my son an artist asked me to make some toys to sell in his store. And I loved the process and I started to make smaller works, like when I was a kid and played with Sylvanian houses. I make things that I want to see or would like to have.”

Before getting out of the light blue car driven by Kenji, I thanked him for his generosity and for participating in Artists’ Collections, and he replied, “I just trust Maiko blindly.” I then thanked Maiko again for the introduction. She replied in the chat, “Kenji has a big heart.”

Interview: Daniela Varone

Photography: Marisa Shimamoto

FOOTNOTES

1Kenji Ide: @works_kenjiide

2Maiko Jinushi: http://maikojinushi.com/

3Goya Curtain is a non-profit art and project space created in 2016 by Joel Kirkham and Bjorn Houtman. Located in Shimo-Takaido Ward, Tokyo, it periodically hosts exhibitions and projects by local and international artists: http://goyacurtain.com/home.php

4Kenji Ide, Banana Moon, Watermelon Sun (Landmarks), 2021, at Goya Courtain: http://goyacurtain.com/kenji-ide.php.

5Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

6Bunchi: https://www.chanchokiu.com/home

7Humo Books: https://humobooks.com/

8Tsukimi means “to contemplate the moon.” Like hanami in spring and momiji in autumn, this Japanese festival pays homage to nature: the autumn moon. Since ancient times, Japanese writings have identified September as the best time to gaze at the moon, when the star is particularly bright. It is the ideal time to show gratitude for the year’s harvest and to demonstrate hope for the next one. This tradition came from China more than 1,500 years ago and became popular during the Edo Period (1603–1868). It consists of contemplating the full moon on the first day of autumn, and the following days. According to Chinese mythology, rabbits can be seen scurrying around the moon on that day, a belief that in turn comes from Buddhism. In Japan it is common to see a rabbit kneading a mochi with a mallet (a typical Japanese sweet Tsukimi dango). The kneading of the mochi is called in Japanese mochitsuki (餅つき) and coincides with the Japanese pronunciation of the word full moon (mochitsuki 望月). During the celebration, wishes can be made, tea is drunk, and music is played/listened to.

9Kenji Ide’s exhibition, A Poem of Perception (2022), curated by Matt Jay, Tanabe Gallery, Portland Japanese Garden: “Ide is interested in the passage of time, both for the weight it carries in our everyday lives, but also for its connection to the experience of a Japanese garden. Drawing inspiration from his belief in the beauty of everyday life—the materials in Ide’s work are familiar and commonplace, creating an accessible visual language that is quietly powerful in its emotional familiarity. For example, Ide views the postcards incorporated into his installation as antiquated sculptures of communication. Unlike today’s digital messages, postcards have their own unique shape, weight, and color. They possess a physicality that people can project their own emotions or experiences onto. As physical objects that must travel through time and space to reach their recipients, postcards foster contemplative dialogue across distances. In Ide’s work, and in a Japanese garden, things are best experienced when one takes their time to open their hearts and minds to be moved by the smallest details. See: https://japanesegarden.org/2022/08/30/kenji-ide-a-poem-of-perception/

10YUGEN / Tsukimi (2019) exhibition by Jiří Kovanda and Kenji Ide at Guimarães, Vienna. The space is directed by artists Christoph Meier, Nicola Pecoraro and Hugo Canoilas. The title contains two Japanese words, on the one hand Yūgen is a word that escapes simple definition, it is the core of appreciation of beauty and art in Japan. It values the power to evoke, rather than the ability to say something directly. “The yūgen is an aesthetic code originating in China that suggests that the work of art serves to give complete form to the inexpressible. Instead of making certain complex or nuanced emotions explicit, it suggests them,” writes Ana Kazumi Stahl in Miradas: literatura japonesa del siglo XX (Glimpses: 20th-Century Japanese literature), Colección Cuadernos, Malba Literatura, 2020. While Tsukimi refers to the celebration of the full autumn moon: to look at, observe or contemplate the moon. The exhibition text is the lyrics of Mitchell Parish’s 1939 song Moonlight Serenade. “I stand at your door and the song I sing is of moonlight / I stand and wait for the touch of your hand in the June night / The roses are sighing a Moonlight Serenade / The stars are lit and tonight how their light makes me dream / My love, do you know that your eyes are like stars that shine bright? / I bring you and sing you a Moonlight Serenade / Let’s wander till dawn in the valley of love’s dreams / Just you and me, a summer sky, a heavenly breeze kissing the trees / So don’t let me wait, come to me tenderly in the June night / I stand at your door and sing you a song in the moonlight / A song of love, my love, a Moonlight Serenade.” More information: https://www.guimaraes.info/yugen-tsukimi.html

11XYZ Collective: http://xyzcollective.org/current.html

12About the exhibition YUGEN / Tsukimi: “XYZ Collective: An Invitation to Shy People”: https://pw-magazine.com/2019/xyz-collective-an-invitation-to-shy-people.

13Jun’ichirō Tanizaki “… I was hesitating about the place I would choose that year to go to see the autumn moon and finally decided on Ishiyama Shrine, but on the eve of the full moon I read in the newspaper that, in order to increase the enjoyment of visitors who went to the mystery the next day at night to see the moon, a recording of the Moonlight Sonata had been placed in the woods. This reading made me instantly give up my excursion to Ishiyama … On another occasion I had already been spoiled by the spectacle of the full moon: one year I wanted to go to contemplate it in the boat at the Suma monastery pond on the fifteenth night, so I invited some friends and we arrived loaded with our provisions to discover that around the pond they had placed cheerful garlands of multicolored electric bulbs; the moon had come to the appointment, but it was as if it no longer existed,” In Praise of Shadows (El elogio de la sombra , Siruela, 2016).

14Nengajō: Japan’s efficient postal system allows all New Year’s greeting postcards to be delivered promptly on January 1 (although they must be delivered to the post office before Christmas). The message usually written on them is “Happy New Year! I hope this New Year brings you better luck, and thank you in advance for your help.” These cards, in addition to being delivered before that deadline, have to be marked with the word nengajō. Then, in order to be able to deliver the millions of cards stored during the previous days, part-time students are often hired in order to multiply the workforce on that day 1 where everything has to go perfectly. This system of receiving and sending New Year greeting cards has been in operation in Japan since 1899. Some of the most popular greeting messages in these New Year cards are: Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu (I hope to count on your kindness and support in this coming year); (Shinnen) akemashite omedetō gozaimasu (I wish you a happy beginning (of the new year); Shoshun/hatsuharu (early spring), that is, you wish that spring arrives soon, and with it the first flowers and the first crops, and of course: Kinga shinnen (happy new year). Source: www.japonismo.com.

15Ulala Imai: : www.ulalaimai.com

16Yu Nishimura: https://galeriecrevecoeur.com/artists/yu-nishimura

17Kayoko Yuki: http://www.kayokoyuki.com/en/

18Soshiro Matsubara: http://soshiromatsubara.com/cv.html

19Masaya Chiba: https://shugoarts.com/en/artist/143/

20Cobra: http://cobra-goodnight.com/cvcontact.html

21Art Center Ongoing: https://www.ongoing.jp/en/

22Ryoko Aoki: @rani2orion

23Akira Takaishi: http://www.akiratakaishi.com/

24Daisuke Takahasi: http://anomalytokyo.com/en/artist/daisuke-takahashi/

25Bunchi (Chan, Cho Kiu), Transition, 2021. See video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nk6hH9hw24Y

26Kenji Ide, Rittai 2 (2018): http://paaet.jugem.jp/?eid=461

27Shintoism is the indigenous religion of Japan, an animistic belief that today is so embedded in the customs of the Japanese that it is impossible to discern in some cases what is religion and what is tradition. In this regard, Soetsu Yanagi writes: “Since these utilitarian objects have to perform a common task, they are dressed, so to speak, in simple attire and lead modest lives. We can almost sense a sense of contentment in them as they greet the arrival of each new day with a smile. They work thoughtlessly and selflessly, performing effortlessly and unobtrusively whatever task they are given.” Soetsu Yanagi, The Beauty of Everyday Things (La belleza del objeto cotidiano, Editorial GG, SL, 2021).

28Hanayo: www.hanayo.com

29Maki Katayama: https://makikatayama.com/

30Masaya Chiba Exhibition, in Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery (2021): https://www.art-it.asia/en/top_e/admin_expht_e/214227/

31Junya Sato: https://www.hagiwaraprojects.com/2017-lightthroughthewindow

32Kohei Kobayashi: http://anomalytokyo.com/en/artist/kohei-kobayashi/

33In the preface to the Japanese edition of Tristes Tropiques, anthropologist, philosopher and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) shares a memory of his childhood and reveals his first love with Japan. His father was a painter, and following the Impressionists dazzled by Japanism, he collected in a box a huge number of Ukiyo-e prints that he gave to his son from the age of five. The Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) print ended up in a box, (which was transformed into a little house) playing the role of the landscape that would be seen from the terrace, and was filled with furniture and miniature characters imported from Japan that were available in a Parisian store in the first decades of the twentieth century. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Other Face of the Moon: Writings on Japan (La otra cara de la luna: escritos sobre Japón, Capital Intelectual, 2012).

34Sylvanian Families toys have been manufactured since 1985 by Epoch Co., Ltd., based in Tokyo, Japan, and distributed worldwide by various companies. The entire line is set in Sylvania, a fictional village somewhere in North America. Most of the families are rural middle class, and many of them own family businesses or have jobs, such as doctor, teacher, artist, news reporter, carpenter, or bus driver. They are designed in the fashion of the 1950s. They may live in large multi-story houses or in homes of their own based on the premise of a vacation home of sorts. The houses are very realistically designed and can be decorated and redesigned. The characters, grouped into families, originally represented typical forest creatures such as rabbits, squirrels, bears, beavers, hedgehogs, foxes, deer, owls, raccoons, otters, and mice, and then expanded to other animals such as cats, dogs, hamsters, guinea pigs, penguins, monkeys, cows, sheep, pigs, elephants, pandas, kangaroos, koalas, and meerkats. Most families consist of a father, mother, sister and brother, and continue to add family members from there, such as grandparents, babies and older siblings. Source: Wikipedia.

35Sylvanian families Biennale: http://xyzcollective.org/sylvanian-families-biennale-2017.html

36Masanao Hirayama: @masanaohirayama

37Welcome to Sylvanian Gallery: https://utrecht.jp/blogs/news/wellcome-to-sylvanian-gallery

38Yu Araki: http://yuaraki.com/

39Japan Style. Architecture, interiors, design. Tuttle publishing, Periplus edition (HK) Ltd. 2005

40Mako Idemitsu: https://makoidemitsu.com/ Mako Idemitsu: Japanese film and video artist, a pioneer of feminist art and visual expression in Japan. “Mako Idemitsu is a pioneer of Japanese feminist art and visual expression. She pursued study in New York following her graduation from Waseda University in 1962, in order to escape the control of her father, founder of the Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd. In 1965 she married the painter Sam Francis (1924–1994), moved to California and subsequently had two sons. However, due to the stress of being the wife of a famous painter, and the sense of isolation she felt as an Asian woman in American society, she began to feel that if she continued to do nothing, she would go utterly mad. Thus, she purchased an 8 mm film camera and began teaching herself to create video art. In 1970, she joined a consciousness-raising group tied to the then-flourishing Women’s Liberation Movement. With the encouragement of the groups’ members, she began using a more professional 16 mm camera.” By Reiko Kokatsu. Translated from the Japanese by Sara Sumpter at https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/mako-idemitsu/

41Yui Usui: https://yuiusui.com/

42About the video A Day in the Life of a Housewife (1977) by Mako Idemitsu: https://makoidemitsu.com/work/another-day-of-a-housewife/?lang=en

43Dollhouse (1972) by Miriam Schapiro: https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/dollhouse-35885