FOOTNOTES

1Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

2Nobuyuki Osaki: http://www.nobuyuki-osaki.com

3University of the Arts, Kyoto: https://www.kcua.ac.jp/en/

4Futon: instead of copying the dictionary definition I prefer to quote two European writers trying to describe to Western readers what a futon is. The first was a Portuguese missionary who traveled to Japan with the Jesuits and wrote in the 16th century: "The people of Europe sleep on high, on beds or cots; those of Japan sleep low on tatami with which the house is matted. Our mattresses are always spread out on beds; those of Japan are by day always rolled up and hidden where they are not seen." Luis Fróis. Treatise on the contradictions and differences in customs between Europeans and Japanese, 1585. The second was a British journalist, translator, orientalist and writer and he wrote from Japan at the end of the 19th century: "I must here interrupt the story for a few moments, to say a few words about Japanese beds. In a Japanese house, unless one of its tenants is ill, you will never see a bed in the daytime, even if you visit every room and look into every corner. In fact, there are no beds in the Western sense of the term. What the Japanese call a bed has no frame, no springs, no mattress, no sheets and no blankets. It consists only of thick quilts, stuffed, or rather quilted with cotton, which are called futons." Lafcadio Hearn, In the Land of the Gods. Travel accounts of Meiji Japan, 1890-1904. Ediciones el acantilado, Barcelona, 2022.

5Hideo Yoshihara: https://www.moma.org/artists/6511

6Hideki Kimura:https://search.nmao.go.jp/en/detail?cls=col1&pkey=41606&dicCls=d_author&dicDataId=556&detaillnkIdx=0

7Tomohiro Kato: https://www.tomohirokato.com/art-works/mimicking/

8Paul Wunderlich: https://www.moma.org/artists/6463

9National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto: https://www.momak.go.jp/English/

10Ukiyo-e: prints produced by the woodcut printing technique that developed and flourished between 1660 and 1868. They are known as “floating world prints,” an expression that makes reference to the pleasure and theater districts of the Edo period.

11Sumida Hokusai Museum: https://hokusai-museum.jp/?lang=en

12Collaborative system of production of the prints: in general, the authorship of the engravings is attributed to the illustrator, who executed the design of the work. However, at least four people participated in the production, all of them masters in their specialty. The most important actor was the publisher, since he possessed the capital to launch such a production, which required a considerable initial investment. “As a businessman at last, and dealing with an industry with a markedly commercial character, it was the publisher who decided what kind of work to do, with what format, what theme to represent (all this, of course, in relation to what the market demanded), and which illustrator, which engraver and which printer he would hire.” The illustrator would sketch the work with brush and ink on paper and discuss it with the publisher, finally stamping it with his signature and the publisher’s logo. The editor took the final design to the official censor on duty, who determined whether the piece could be published or not, and the official “approval” stamp was stamped on the wooden plates. Then it was on to the carving of the set of plates or blocks in the engraving workshop that was hired. “The engraver, or hori-shi 彫師, would glue the final drawing on its front side to a properly prepared block of cherry wood, using a rice paste. With his fingers he would remove the thick back layers of the paper glued to the wooden block so that it would become transparent. He would then proceed to carve and roughen the wood block. … The printer, or suri-shi 措自帀, was the master who would complete this path. The pigments used in the printing of these woodcuts were of natural origin and had no fat base, so their diluent was almost always water.” Amaury García Rodríguez, Cultura popular y grabado en Japón: Siglos XVII a XIX, 2005. [Popular culture and engraving in Japan: 17th and 19th centuries]

13On the number of copies made of an Ukiyo-e print: the lifespan of a cherrywood plate was considered to be 250 copies, but recent studies indicate that the same block could produce between 3,000 and 10,000 prints. “Of course the final number of copies depended on the demand for the stamp or series in question, and there were cases where it was necessary to re-carve another set of plates. The standard figure suggested at the time would be about 5,000 prints, although again in Fukiokaya’s Diary it is mentioned that ukiyo-e woodcuts were published in units of 1,000 copies.” Amaury García Rodríguez, op. cit.

14Kanae Yamamoto: https://www.artic.edu/artists/60695/yamamoto-kanae

15Christine Greiner, Lecturas del cuerpo en Japón y sus diásporas cognitivas, Zettel Publishing Agency, 2018. [Readings of the body in Japan and its cognitive diasporas].

16Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908), an American Japanologist, art historian, translator, and poet, was one of the many foreign specialists hired by the Japanese government to modernize the country during the Meiji period. He was one of the first serious interpreters of Japanese culture, and his writings and lectures were a reference for Western dealers and collectors of Japanese art. More info: https://www.globalsquaremagazine.com/2017/12/10/ernest-fenollosa-una-vida-entre-oriente-y-occidente/

17Some art dealers of the time were: Siegfried Bing, Hayashi Tadamasa, Matsuki Bunkio and Yamanaka Sadajiro. It's very interesting the print collection of the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright—who sold part of his personal collection to the MET, among other public institutions in the United States.

18Irene Seco Serra, Historia breve de Japón, 2010. [Brief history of Japan].

19Julia Meech. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan. The architect's other passion. Japan Society and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., publishers, 2001.

20Tadanori Yokoo: https://www.moma.org/artists/6502 and see video of his current paintings: https://youtu.be/KnXXYHCcKIw

21Yui Usui: https://yuiusui.com/

22William Kentridge: https://www.kentridge.studio/

23Takeshi Mita: https://mita-takeshi.tumblr.com/

24Naomi Ashida: https://ametsuchi.katalok.ooo/ja

25Yoshinobu Nakagawa: https://nomart.co.jp/gallery/artist/yoshinobu_nakagawa.php

26Shiochi Ida: https://www.moma.org/artists/2795

27Ei-Q or Ei-Kyu or Sugita Hideo (1911–1960) (https://www.momat.go.jp/en/artists/aei001) . He was an avant-garde artist who worked between surrealism and abstraction in painting, photograms and, later, prints and lithographs. During the 1930s he became interested in photography and photograms. In 1936 he published the influential book Nemuri no riyu, which brought him to the forefront of the Japanese avant-garde. He was an influential leader of several artists’ associations in the pre- and post-war periods.

28Masayuki Arai: https://standingpine.jp/en/artists/10

29Exhibition Galley Parc, Kyoto: https://www.galleryparc.com/pdf/2019_pdf/20191122_osaki_pdf/GalleryPARC_Release20191112.pdf

30Aichi Triennale: https://aichitriennale.jp/en/ en esta edición two Argentine artists participated in this edition: Claudia Del Río and Florencia Sadir. See artists: https://aichitriennale.jp/2022/en/artists/index.html. The title “Still Alive” is inspired by the series of the conceptual artist On Kawara, born in Aichi.

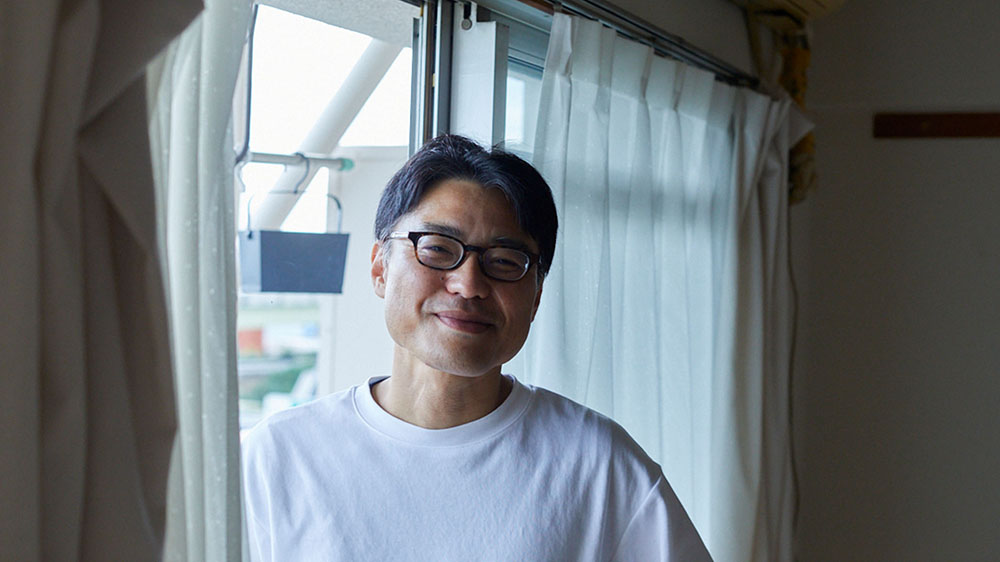

“Sometimes I buy works imagining that I live in a big house.”

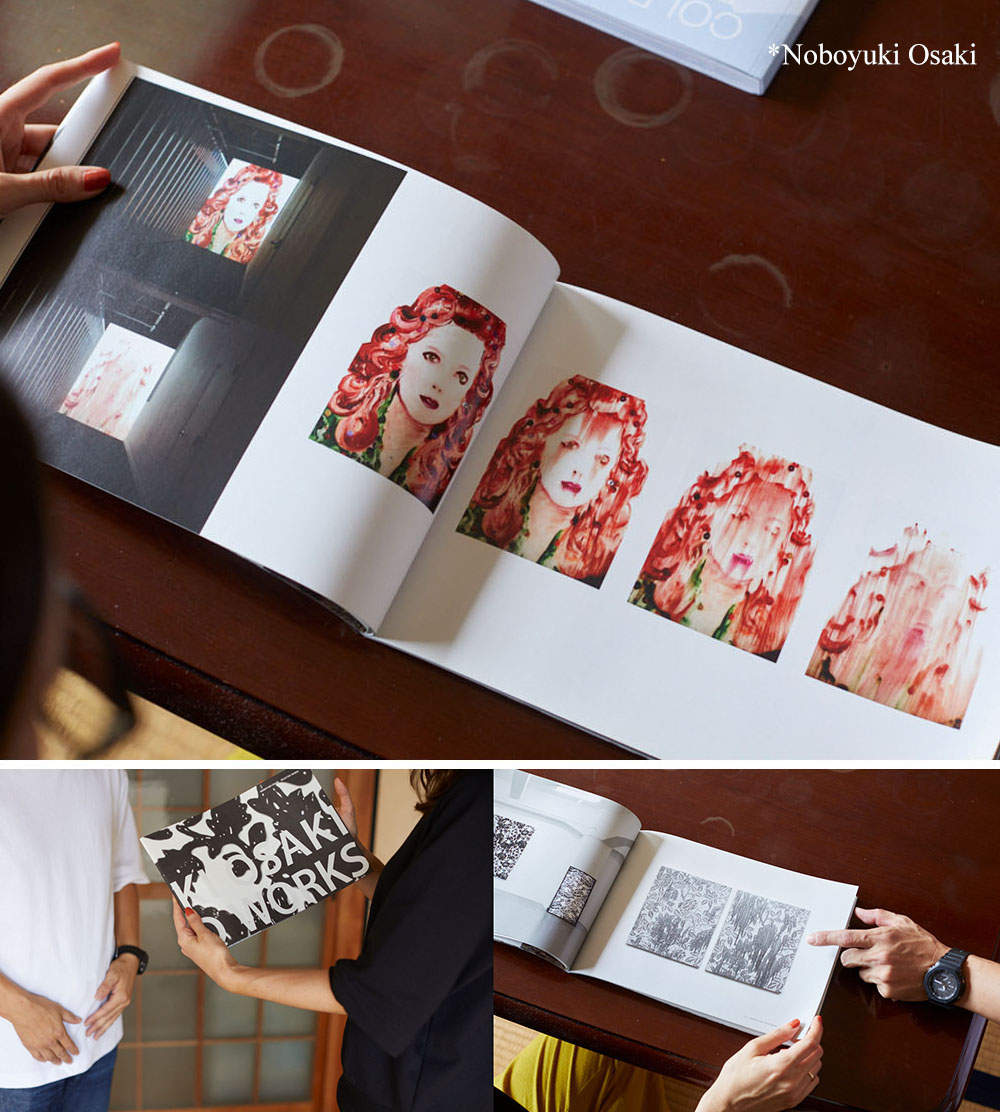

Nobuyuki Osaki

On Wednesday, September 21, I wake up early in capsule 523 of the Nine Hours Hotel. A cold light streams in through the window, and in cautious silence I lift the blackout that separates me from my roommates. I count nine pairs of black slippers. I imagine them wearing the same mandatory pajamas I’m wearing, but I never see or hear them. I’m in the city of Nagoya and for a few days I have been avoiding a typhoon that is advancing towards the north of Japan. Capital of the Aichi prefecture, located in the center of the island nation and three hours by Shinkansen from Tokyo, Nagoya is the fourth largest city in the country.

Marisa Shimamoto1, photographer for this project, travels that same day from Tokyo for the interview. We meet at the scheduled time at the central train station and connect with the subway to Hongo. Around 11 a.m., we ring the doorbell at the apartment of Nobuyuki Osaki (1975).2.

In our email exchange, almost a year ago, he wrote from Stuttgart: “I have a small number of works, maybe twenty? However, my apartment is very small, and I only have a few works on display, most of them are in storage or in boxes. In spite of that, I sometimes buy works imagining that I live in a big house.”

The apartment doesn’t feel as small to me as I had anticipated. Perhaps because it is quite bare and has almost no furniture. As is the case in rooms with tatami mats, the table is low and we sit on the floor. It’s autumn but it feels like summer, the windows are wide open and you can hear the murmur of cars in the distance.

D. “Nobuyuki, do you consider you have a collection?”

N. “I don’t consider myself a collector, but I do think I have a collection. I’m interested in works that have to do with my own experience, as I told you in my email. My collection is basically of engravings, because it is what I studied at university, and it is very personal, it includes people I admire, who had some impact on my life. Most of the works in my collection are from western Japan, from the Kansai region (cultural and traditional heart of Japan), from the cities of Osaka and Kyoto.”

D. “So it has more to do with affection?”

N. “It is not only that, because there is a work by a master that I respect, but he used to bully me a bit and it is a love-hate relationship. These works formed me, but not only in an affective sense. It’s a bit like Dragon Ball, I’m trying to gather all the balls I’m missing, ha ha.”

M. “Do you need them?”

N. “Not necessarily. Even if I don’t have them, they are present in my memory.”

D. “Artists’ Collections are like a puzzle, you put together a portrait of each artist through their collection. The book cover I brought as a gift is a synthesis of that idea. You were born in Osaka, but you studied at the University of the Arts in Kyoto3, about 90 kilometers away. Why did you choose that city?”

N. “When I decided to study art, my first impulse was to study in Tokyo, but for economic reasons my parents suggested I should study closer to home. I still had to travel three hours a day, between going and coming back.”

D. “Oh, but you were still living in Osaka?”

N. “Yes, I did for two years,” he says, and laughs.

D. “And why didn’t you study in Osaka?”

D. “I see, I didn’t know that Kyoto University was a public one (founded in 1880, it is also the oldest university in Japan). And how did you end up living in Nagoya?”

N. “Because I was offered to teach at the Aichi University of Fine Arts and Music, and to be a professor at a public university you have to live in the same city.”

D. “How long have you been living here?”

N. “Fourteen years.”

D. “So you grew up in Osaka, studied in Kyoto and lived most of your adult life in Nagoya.”

N. “Yes, I grew up in deep Osaka,” he says in English, “not in the central area, but in a city called Kishiwada, very dangerous.” The three of us laugh loudly, because Japan is the safest place on the planet. “Let’s say, the first years of university I stayed in Osaka because I had a place to live. Then I stayed in Kyoto for thirteen years, during part of the university and after graduation; although I went back to Osaka temporarily for two years, to be precise.”

D. “I understand, relatively close to everything.”

N. “I can move the futon4 away if you prefer. I didn’t know whether to keep it for the interview, ha ha.”

D. “No! Please leave it, I love it.”

N. “At first I thought about putting it away, but then I saw the pictures of your project and I left it.”

D. “You know that in Argentina we don’t use a futon, I think it’s a good idea to leave it. I’m more interested in showing how you really live.” (Laughs)

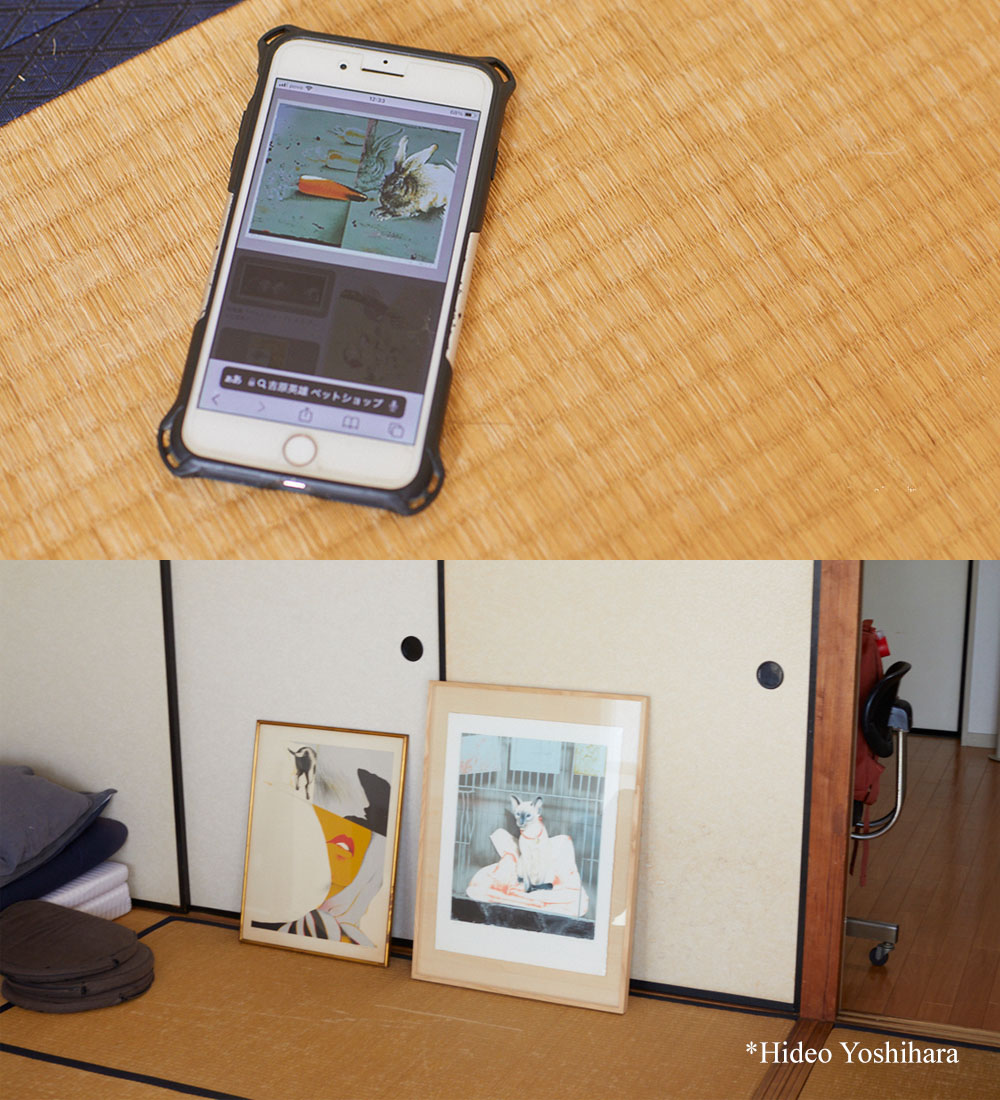

N. “This is one of the two works I have by hangaka Hideo Yoshihara (1931–2007)5. He is very well known in the field of lithography in Japan. He was the teacher of Hideki Kimura (1948–)6, so he was my sensei’s sensei.”

D. “We have to make a graph of the hanga senseis later.” (I write his name in my notebook in the way artists are named in Japan. First comes the last name, then first name. In order to make it easier for western readers, I’ll use the reverse mode in these interviews).

N. “Sure, yes, I was his student for a year, but then he retired.”

D. “So you knew him.”

N. “Yes, yes, yes, yes. In fact, it was because of him that I began to study printmaking. In the first year of art school you could choose between three orientations: traditional Japanese painting (nihonga), oil painting, or sculpture. At that time, you did not yet have the option of taking printmaking. I chose the first option, but it seemed very conservative, I didn’t like it. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to continue or not, and one day I came across a flyer of a Yoshihara exhibition and discovered that he was teaching at my university, so the second year I chose printmaking and well, as I told you, he retired after a year. He was very busy and his assistants were teaching too, so I didn’t see him that much either.

D. “His aesthetics is very eighties, isn’t it?”

N. “It is from the seventies, really. He was active during the fifties, sixties and seventies. What I am about to tell you is a bit difficult and very deep. In a congress he explained that to be a printmaker is to think about art under a certain structure, it is to think about the image and decompose it. A few years after we graduated, we did a group show with other artists and, as he was very famous, he was in charge of the speech. He went through the whole show, looked around and said: You don’t understand what printmaking is, it’s breaking the frame and creating something, it’s not just making prints. Nobody said anything, obviously, because he was a master”, top of the senseis, he says, and I love the expression. “Each student presented his work, and I did too. At the event after the exhibition nobody dared to talk to him, and he approached me, we talked and he apologized. He told me, You do understand,” he recalls the anecdote with a laugh, “and this made me happy, because I think that my classmates did not understand my work.”

D. “I see. And how did you get this work?”

N. “I bought it in a secondhand bookstore, which sometimes sells this kind of engravings.”

D. “Yes, I saw some of them.”

N. “In this work he uses two techniques: lithography and copper printing. It is something strange, in general if you use copper you don’t mix lithography, because with copper you have to wet the paper and to make lithography you can’t use wet paper at all. But Yoshihara was one of the first to experiment with these two techniques, to incorporate copper printing to lithography. He was able to show these two worlds in the same work.”

Framed and leaning against the sliding doors are two works by the same artist.

D. “Marisa, that’s a good shot! Nobu, don’t move, it looks perfect there”. We all laugh while we make the works pose. “What year is this other work, the cat one?”

N. “It’s from 1979,” he says checking on the back of the work, “this was a series he did about pet shops. I really wanted to buy the rabbit,” he says with a laugh.

D. “And what happened?”

N. “Even if I had found it, it is a more expensive work.”

D. “Why? Is that work better known?”

N. “Originally the complete series was sold, but now you can get them separately,” like a good professor, he looks for the work in his cell phone so we can see it. “I like it because it has an energy similar to Albrecht Dürer’s hare (master of the German Renaissance), right?

D. “I understand, yes, if you get it, please let me know.”

N. “I always see it, but I find it expensive, ha ha, there are only 65 copies in the world.”

To fight the heat, Nobuyuki treats us with Barley, a typical drink of this season, a cold infusion based on roasted barley grains. Because I am used to Asian flavors, I find it delicious. I bring to share Baumkuchen, a traditional German pastry cake. Although it is not a dessert of Japanese origin, it almost could be, since it is very present in bakery stores and there are individual versions available in all konbini stores.

N. “It is a dessert that is given as a gift for weddings, its circular shape has to do with the idea of infinity and also with the rings of the trunks when they are cut.” Hence its name baum (tree) and kuchen (cake).

D. “I chose it also because looking at your CV, I noticed that you have a strong link with Germany.” I call it Germany and he calls it Deutschland. “On the one hand, you went to Düsseldorf when you were very young, in 2003, and you came back almost 20 years later, in 2021, to Stuttgart, but I also saw that you exhibit regularly in a gallery in the city of Hamburg.”

N. “Yes, when I was young, there were many countries I wanted to visit, but in Deutschland I found many artists I was especially interested in, such as Sigman Polke (1941–2010). And I also knew that education there was free, and for me it could be a possibility if I came to study abroad. At that time, if I decided to leave Osaka, I wanted it to be somewhere abroad.” While we talk, we leaf thorough a book by the German artist. “The first time, I was invited by a German program. Do you know the Goethe?”

D. “Yes, of course.”

N. “I applied for the residency they offered and I was selected, but then I had a personal interview with the German director here and my English was very basic,” he laughs as he recalls the story. “There were many questions, but the last one was What do you expect from this experience? and my answer was: I don’t know. I think he was expecting a more elaborated answer,” he says laughing, “that I would tell something about the impact that German art could have on me or something like that, but the reality is that I didn’t know what could happen.”

D. “Well, at some point that’s true, you never know what is going to happen in an experience like that, each path leads you to the next point.”

N. “Yes, I did not know that I was going to end up in Nagoya.”

It is usual to find some detours in the artists’ collections, some foreign objects that slip through the window. In Nobuyuki’s case it is the clock. In his house, I count four or five of them, of different shapes, origins, and sizes.

N. “I bought the big one in Deutschland last year. The institution I was in (Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Kunst Stuttgart) had a relationship with the Bauhaus, as did the professor, who had worked there for a long time, so I wanted to buy something related to the Bauhaus. I was looking for something by the designer Max Bill (1908–1994), and I couldn’t get it, but I found something similar at the flea market and bought it.”

D. “In fact, you are one of the few people who still wear a wristwatch.”

N. “Yes, I love them, I have older ones fixed but they always break again.”

D. “It is a museum piece now, ha ha.”

N. “I buy new ones. This one is more formal than the others, I use them depending on the occasion.”

D. “And this heavy pencil?”

N. “The pencil is actually an iron sculpture by Tomohiro Kato (1981–).”7.

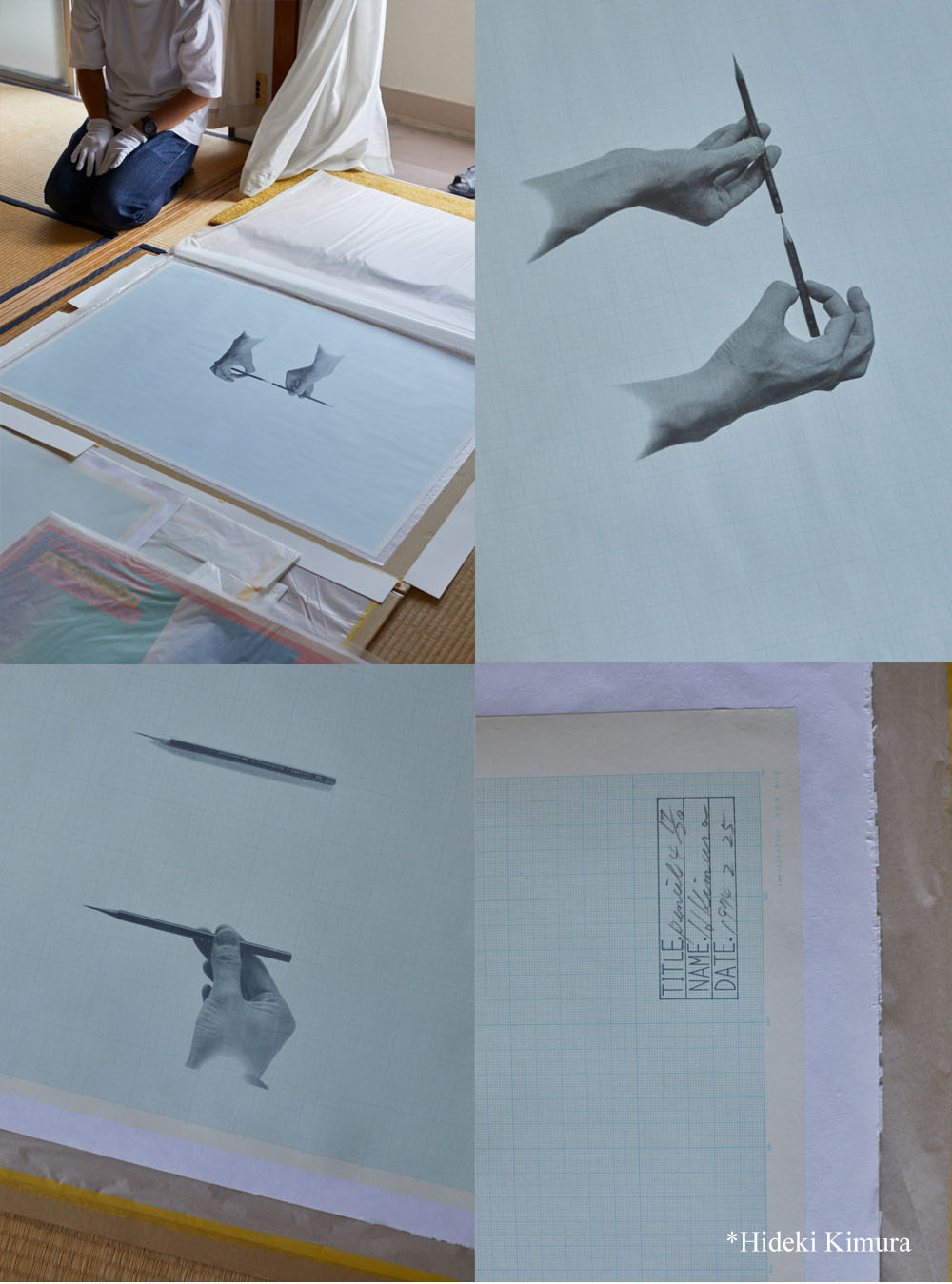

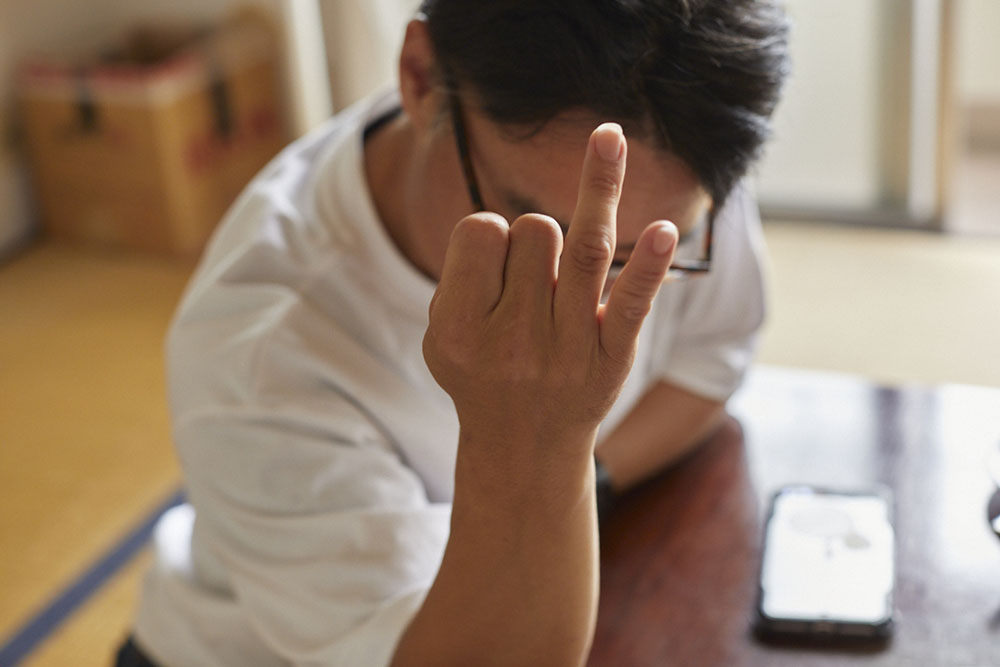

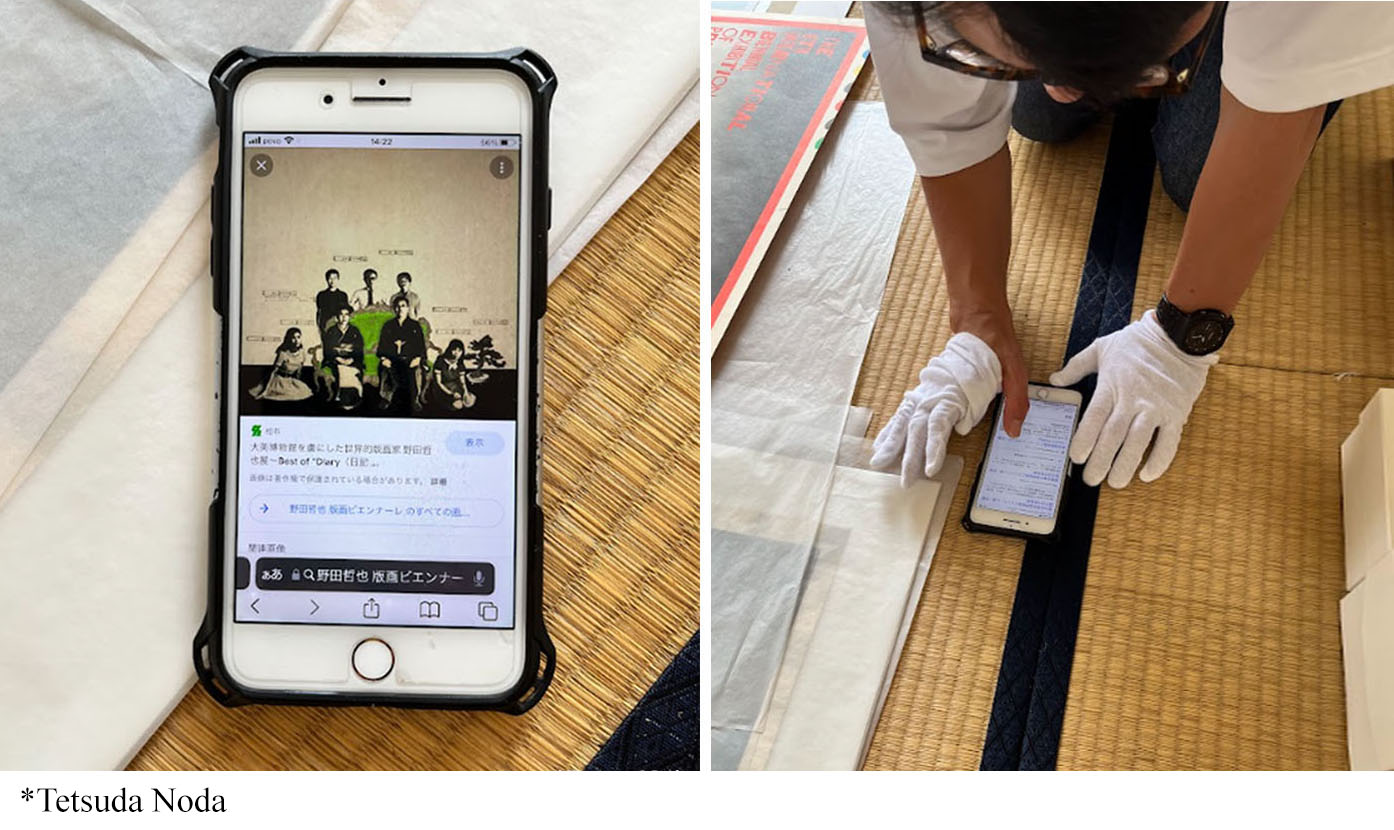

I like to call this part of the interview: museum moment. Sitting on the tatami mat, Nobuyuki puts on white gloves to handle some larger unframed works that he keeps neatly wrapped in white silk paper.

N. “This other work is precisely by a German artist as well, he is a lithographer, his name is Paul Wunderlich (1927–2010).”8 I google him at the moment to see who he is—his very white hair and mustaches catch my attention.

D. “Where did you buy it?”

N. “I bought it at an auction, five or six years ago. When I was a student I found a book in a secondhand bookstore and it inspired me a lot. I loved his work. He is one of the artists who influenced me during my education, and many years later I found it at an auction, and I wanted to have it.”

D. “Do you always keep it wrapped?”

N. “Sometimes I change the image of the frame and hang it. Does the interview come in handy?,” he asks both of us. Marisa has the double responsibility of doing the photographic record and translating, all at the same time.

D. “Yes, it’s very good! Daijoubu.”

N. “This work is by Hideki Kimura, from the series of pencils.” It is a photographic image of a hand holding a pencil, printed on graph paper. “This is the small version, I have a larger one, I bought them separately.”

D. “As indicated in this beautiful signature, it is a silkscreen from 1974, and from what I understand it is also in the collection of the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto9.”

N. “Yes, yes, yes.”

D. “Did you also buy it at auction?”

N. “Yes, it is an interesting work because it is the work with which the artist graduated from the university, with which he began his career.”

D. “His early works.”

N. “A famous curator saw that exhibition of his graduation and invited him to participate in the 9th International Biennial Exhibition of Prints in Tokyo, and he won a prize for this silkscreen. It’s a funny story, when I bought it three years ago and it was delivered to me I noticed that the paper had a crack in it. And since he was one of my teachers, one day I told him about it, and he said: Bring it to me. He got rid of the one that was damaged, and replaced it with this one, which is the same as the one I had bought. He made me promise to mount it on another piece of paper so it wouldn’t break, but I still haven’t done it. In this other work I did it, but not yet with this one.”

D. “I understand, because paper is very difficult to preserve.”

N. “I did it myself, you use a glue that can be removed, that’s how this kind of work should be preserved. I should do it with the rest.”

D. “Homework.”

Another work by Hideo Yoshihara appears.

N. “I haven’t unpacked it for two or three years, every time I buy something new it’s an opportunity to see how the rest is. This one is from 1972.”

D. “How nice! It’s like a plate, with lots of colors.”

N. “It’s from the series Mirror of the mirrors that he did in New York.”

D. “What technique is it?”

N. “Lithography.”

I am opening a parenthesis. How much do we know about Japanese engraving? I guess not much, but I’m sure we all know Hokusai. Any relevant museum in the world has in its collection a copy of Under the Wave of Kanagawa by the master of Ukiyo-e10, Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). In Tokyo, of course, he has his own museum. A few blocks from the Sumida River, in the neighborhood where he lived for almost 90 years, is the Sumida Hokusai Museum11, designed by the SANAA studio (Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa), one of the most influential in contemporary architecture. When I visited it years ago, an exhibition celebrated the 170th anniversary of his death, and displayed a copy of The Great Wave on not just one, but two different floors of the museum. To better understand what his life was like 200 years ago, you could also see a life-size model of his studio with robots representing the artist and his daughter at work (there is nothing more Japanese than that).

Printmaking, in many cultural circles, is considered “a minor art.” The commercial and collaborative system (publishers, illustrators, copyists, engravers, printers, writers)12 through which Japanese illustrated books and prints were produced in the Edo period (1603–1868), known as Ukiyo-e disqualifies them from the category of “great art.”

Unlike the painter, the print artist did not have full control of his works, as it was the publisher who owned and financed the project, and decided what kind of work to do and whom to hire. The illustrator would draw a design and give it to the publisher, who, with the censor’s approval and the official stamp, would take it to the engraver to create a plate, which would be given to the printer, who would complete the process and produce as many copies as the publisher ordered13.

In the early years of the 20th century, Kanae Yamamoto (1882–1946)14 was still a university student when his print The Fisherman (1904) marked the beginning of the Sosaku hanga (creative prints) movement. This is considered the first print made by a single person, breaking with the previously established convention of division of creative labor and publisher distribution. In 1912, like many other artists, Yamamoto traveled to Paris, the mecca of Western art. Four years later, World War I was raging in Europe, and it took him six months to return to Japan. On the way back, via Russia, he also witnessed the beginning of the October Revolution. Shortly before his death, at the age of 64, he destroyed his printing blocks with an axe and only a handful that he had given to friends were saved.

Yamamoto lived his youth in the last years of the Meiji period (1868–1912), which, among other fundamental changes, implied the (forced) opening of Japan to the world and, with it, the modernization and accelerated industrial development of the country. For the history of art it was an important moment, marked by the dissemination of “Japanism” in Europe and the United States and by its repercussions in Japan. It is at this time when we can find the germ, and the bidding, of two major movements: Yōga (Western-style painting) and Nihonga (Japanese-style painting), two terms that were coined at this time to differentiate them.

Follow me a little more, as this is also important. Another fundamental concept born here, in the context of the universal exhibitions, is that of Bijutsu. “Until the 19th century, the Japanese showed no interest in constructing an aesthetic theory,” writes Christine15, and she further clarifies that “unlike other terms relating to art, proposed by intellectuals or artists, Bijutsu (fine arts) was suggested by government officials, during the preparations for the renowned Vienna Universal Exposition (1873).” And she continues with this anecdote that I find quite didactic and amusing: “In the midst of these discussions and the first attempts to organize a proper lexicon for Japanese aesthetics, the Meiji government invited the orientalist Ernest F. Fenollosa16 to give lectures on philosophy, aesthetics, art and literature at what

would later become the Imperial University of Tokyo. … The translators recruited to interpret him in the lectures lived in crisis. They needed to improvise an arsenal of terms to translate what Fenollosa said, since, in Japan, the ideas of authorship and individual creation did not exist until then …”

In those years, we were saying, the West discovered at the same time Japanese prints (Ukiyo-e) from previous decades, thanks to books and the work of art dealers17. When the production of engravings was decreasing in Japan, European artists became increasingly interested in them, to the point of generating a whole fashion called “Japonisme.” The great successes of the Edo period woodcuts were reprinted for the foreign market and sold in Paris, London, Boston, New York and later in Chicago.

Imagine the “Bijin-ga” (beautiful women) by Utamaro (1753–1806), the 36 views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai (1760–1849) and the 53 stations along Tokaido by Hiroshige (1797–1858) circulating among the impressionist painters. Artists such as Monet, Van Gogh, Cassatt and Toulouse-Lautrec fell in love with their images and “art nouveau drank greedily from the Japanese fountain” . But, in the new world, 18th-century prints were expensive; for example, a millionaire Detroit businessman paid $80 for a design by Utamaro in 1894. For an artist like Degas these figures were out of his budget, and he had to trade his own paintings for prints for his collection. Let’s think that in their place of origin, and due to their low cost of production (at least, already in the first half of the 19th century), Japanese prints circulated among the popular classes and cost the same as a ration of soba noodles19.

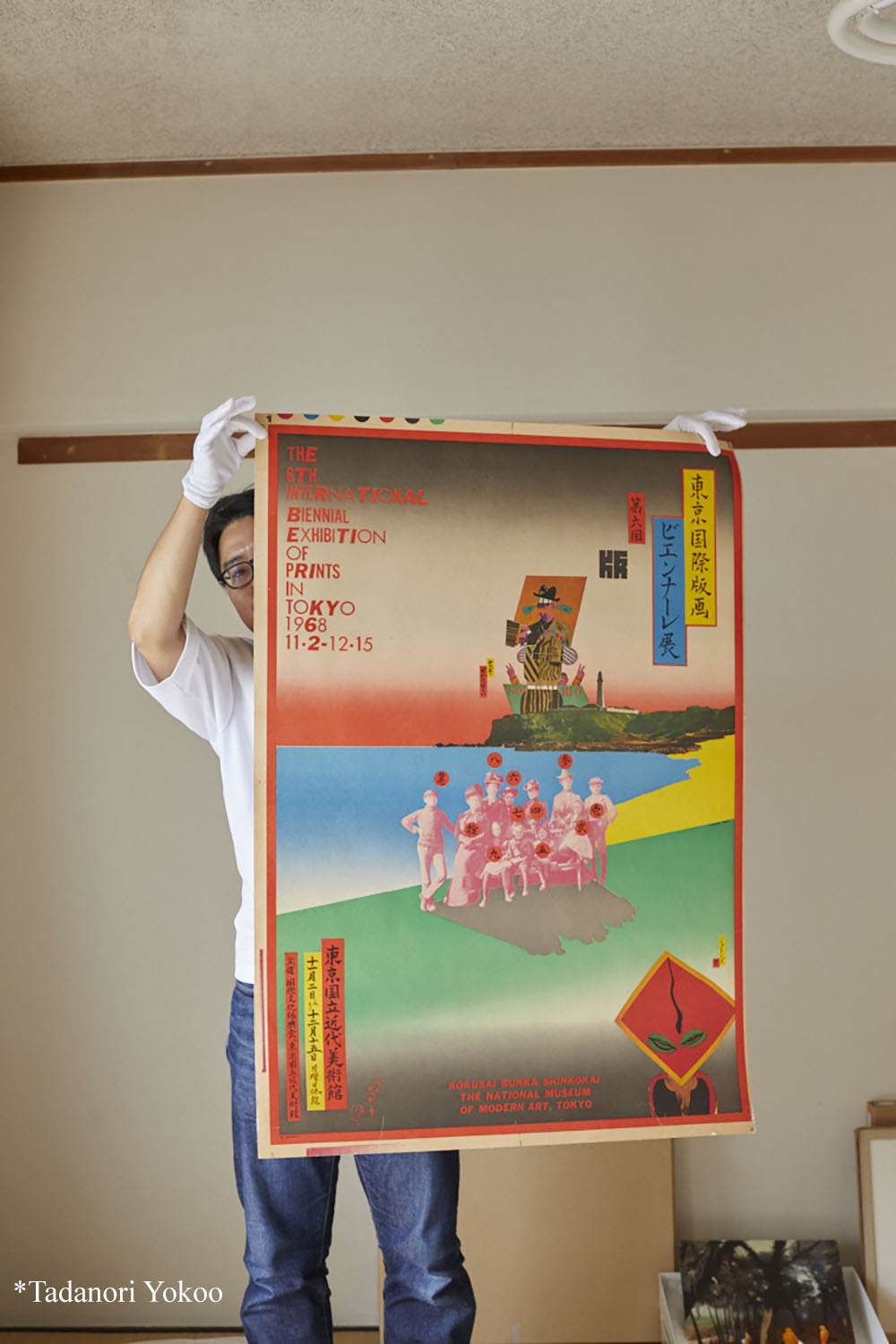

After this brief (but long) introduction to the history of Japanese prints, let’s return to the “museum moment” of this interview, in the living room in Nagoya. With loving movements, Nobuyuki opens the layer of white paper that protects a colorful poster. It’s the kind of work that, without ever having seen it, you get the impression you know it.

It is about a very famous artist of the second postwar period, Tadanori Yokoo (1936–)20, a set designer, graphic designer, illustrator, engraver and, in his later years, also a painter.

N. “This piece from my collection is a poster, more than a work of art,” like a good teacher, he starts contextualizing the story.

D. “Do you know him, Marisa?”

M. “Yes, yes, he is very famous.”

Known as the “Japanese Warhol,” during the sixties and seventies he designed several album covers and concert posters for Japanese groups like The Happenings Four, Takakura Ken, Ichiyanagi Toshi, Asaoka Ruriko and international bands like Santana, Miles Davis, The Beatles, Emerson Lake & Palmer, Cat Stevens, Earth Wind & Fire, and Tangerine Dream. In 1981, after visiting a Picasso retrospective at MoMA, he retired from commercial work and devoted himself to painting.

N. “This poster was made by Tadanori Yokoo to promote the 6th International Biennial Exhibition of Prints in 1968, which was held at the National Museum of Modern Art. The artist who won the prize at the biennial was Tetsuya Noda (1940–),” he says, while looking for the image of the work in his cell phone. “Look, he won with this work.”

In 1968, just four years after graduating from college, Noda received the Biennial International Grand Prize “for the bold combination of photography with the traditional woodcut.”

“What is interesting is that Noda’s award opened a great debate at the time. Yokoo’s poster, itself a print, depicts a family, and Noda wins the biennial with a print whose image is also a portrait of a family, his own. The difference is that Yokoo’s work is considered a poster, and Noda’s, on the contrary, a work of art. And this generated a great debate and a broadening of the concept of printmaking; from that moment on, more experimental prints began to be made. This opening, paradoxically, after a few more editions, led to the end of the Biennial Exhibition of Prints in 1979 (it was held between 1957 and 1979).

D. “This poster marks a key moment in the history of printmaking at that time.”

N. “Yes, that’s why I chose it, it opened a door.”

In another sector of the house, we find a more visible part of the collection.

N. “When my friends come to visit my house they tell me, Everything is stripped, you have nothing, because I keep it clear and I keep everything in the other room, which I use as a storage room. But the bathroom is like an exhibition space,” he laughs. “It has to do with a technical problem, in the main room the walls are concrete and cannot be nailed, but in this sector of the house they are made of wood, so I have more things here.”

D. “You have a small zoo in the bathroom: there is a bear, a dog, a zebra, a turtle.”

N. “I brought the animals from Deutschland, and this plate is a Chinese antique.”

D. “I love the label. What does it say?”

N. “It certifies that it is a real antique. This little guy is from Taipei, Taiwan.”

D. “Interesting decoration you have here and, of course, the calendar. Whose work is this green one?”

N. “Yui Usui (1980–)21, she is an artist who works with mixed media. I’ve had it for 11 years, I bought it in an art gallery (Ain Soph Dispatch).”

D. “Looks like debris, I like it. And this other one, is it a collage?”

N. “It is by Kayoko Oguri. In this sector of the corridor, I have three walls available, and I can change these small works.”

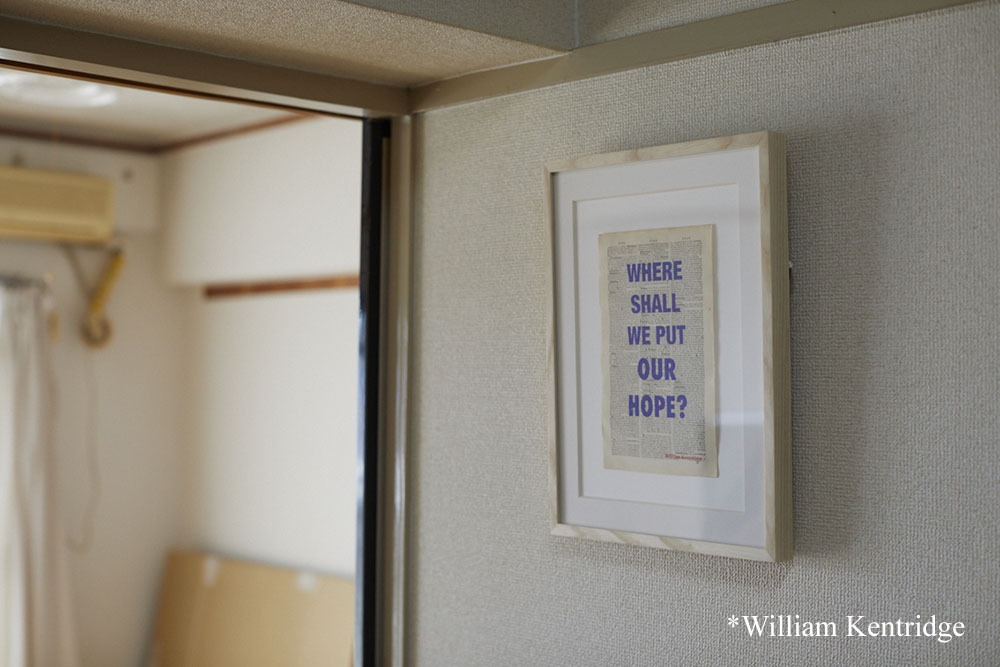

D. “I know William Kentridge (1955–)22.” Printed in blue on a dictionary page, it reads: Where shall we put our hope?

N. “Yes, very famous artist. It’s a multiple, because he’s a very expensive artist. I bought it last year. I went to visit his exhibition and the catalog came with a work. I knew him as an artist, but the exhibition was impressive, so I went back several times. The book was for sale, but I did not know that it came with the work inside and it seemed very expensive. I hesitated a lot to buy it, but in the end I did. There was just one copy, that had a mark, a small damage, and they asked me if I wanted to buy it the same and the employee told me that it came with this work inside, because they were all different pieces. Since it was a time of pandemic, the phrase resonated with me and seemed perfect. Even the fact that it was damaged made sense to me.”

D. “And this photo of a bike? Marisa thinks she has seen it somewhere else.”

N. “It is by Takeshi Mita (1979–)23He takes pictures of pre-existing images; this is a picture from a magazine.”

D. “Ah, that’s the edge of the page, I see.”

N. “I bought it in an art gallery in 2010. I usually change the works on this wall, but this is a very simple image and I really like it.”

D. “It’s next to your bike, which has an amazing design (Vanmoof X3).”

N. “I used to ride my bike a lot when I was in Deutschland and I often saw it on the street and I loved it, it’s a historical design. When I brought it and put it here I just realized the coincidence, ha ha.”

D. “It seemed all planned.”

N. “At first I put the image because I liked it, but once it was here it became something mine, and it made more sense.”

D. “It is like a dialogue between two works of art. The design of this bike is also art.”

N. “I believe that product design is art, yes.”

Neatly stored in its box, there is also a set of cups with their plates produced by an artist. A polar bear on the handle adds to the pantheon of animals.

N. “I didn’t buy these mugs thinking about my collection, but rather to use them.”

D. “And did you use them? Because it doesn’t seem…”

N. “No, I think I’ve had them for about four or five years, but I haven’t used them for the first time.”

D. “Beautiful.”

N. “Yes, they are beautiful. They are from Naomi Ashida (1975–)24.”

D. “Use them tomorrow at breakfast.”

N. “Yes, maybe I will,” he answers, and laughs.

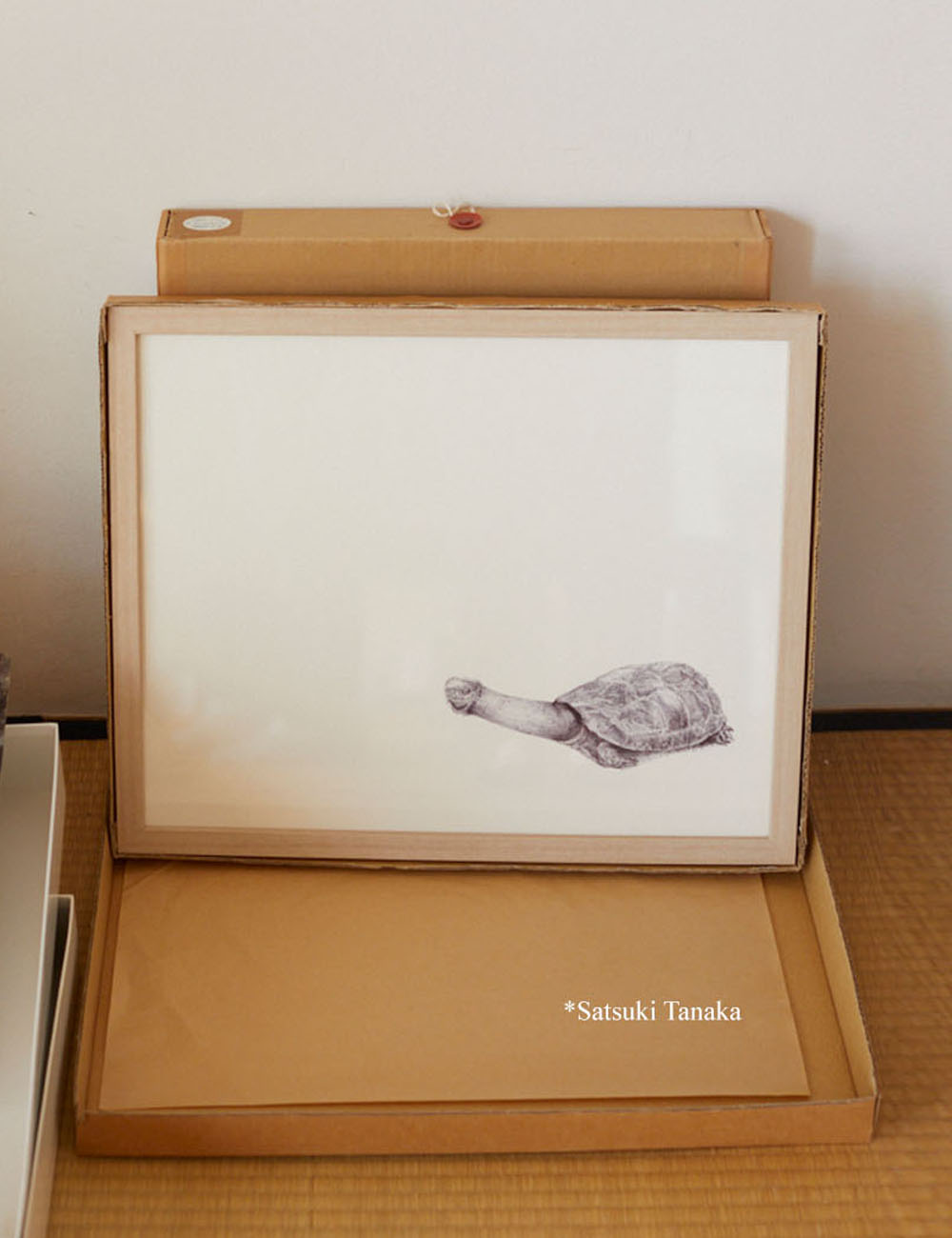

We still have to see a pair of works. Framed, they rest on the tatami of the almost empty room.

N. “This work in the bowl is by Yoshinobu Nakagawa (1964 - )25.

D. “How did you get it? It is from the nineties, isn’t it?”

N. “Yes, from 1996, his peak was in the nineties and two thousand. This artist is a little older than me, he is approximately ten years older, so, a generation before mine. This work is from the time when I was a student, which was between 1994 and 2000, about twenty years ago. At that time, I was familiar with his work and came across his exhibition at a gallery in Kyoto by chance. He was not well known among the general public, but he was well known among artists. Years later I found the same art gallery in Nagoya (Nob Gallery) and bought it.”

D. “And the work next to it?”

N. “Shoichi Ida (1941-2006)26. I bought it at the Yahoo auction. He was much older than me, I didn’t know him in person, but we went to the same university. He was a very avant-garde artist and I very much share his way of thinking, conceptually he went beyond printmaking. I was looking for a book on printmaking and I came across this work, it was a coincidence. Prints are destined to be forgotten, they are not properly preserved and so I thought it was my mission to buy it and preserve it. If it was not sold, who knows how it would end up. It was also very cheap and in general his work is much more expensive. At auction the value of his work is not very high, since there are many copies, but I knew the value of this artist and I felt I wanted to take care of it.”

D. “MoMA has several of his works from the seventies in its collection. He is one of the most important printmakers of the ‘Golden Age’ of contemporary printmaking.”

N. “Yes, that’s true, and they have a edition of this work as well. This one is from the nineties, and it is a classic engraving—the tools, the techniques, etc.—, but I identify with the way the artist thinks, that’s why I wanted to have one of his works. I collect works with which I share a common universe. I studied printmaking, but in my current work I work with video and make installations, not necessarily prints. Printmaking today is much broader, it has expanded.”

D. “If you could buy any work, which one would you buy?”

M. “The rabbit,” Marisa answers quickly.

N. “Yes, Yoshihara’s rabbit! (A year later, in 2023 and coinciding with the year of the rabbit Nobuyuki lets me know by email that he finally bought the work). Well, I have works by my masters and their masters, I still need to have works by the masters of my master's masters, but those are already in the museum collections, ha ha.”

D. “We can end up in the Ukiyo-e if we go to the end, ha ha ha.”

N. “There is an artist I love that I would like to have, his name is Ei-Q (1911–1960)27, he is from the first half of the 20th century, previous to the artists I have, who works with photograms, photocollage. Ei-Q was able to resume his work after the war and in 1951 he created the group Association of Democratic Artists in Osaka.”

After going through the works of his sensei, and some great names in the history of printmaking in Japan, a work by a student of Nobuyuki, from the Aichi University of Arts, appears.

N. “This artist’s name is Masayuki Arai (1984–)28 . It is a collage: a photograph taken from a magazine, and it is also painted with oil. First, he places the image, and expands it driven by his own imagination, he continues it. And then he brings another image from another magazine… and so on.”

D. “Was it a gift?”

N. “No, I bought it from him.”

D. “It’s a good way to support the work of young artists, isn’t it?”

N. “Yes, sometimes I buy small drawings of young artists. Although in the last few years prices have gone up a lot, ha ha, and I have my budget. In general, I buy art that is related to my roots. And in this case, this student was close to me. Actually, he was not directly my student, but he belonged to another class and his teacher asked them to follow very strict directions, and he felt a lot of pressure. He felt trapped with him, he wanted to draw, but he couldn’t, and then he started to make 3D designs. At that

time, we talked a lot, and when it was his turn to do a piece of work for his graduation show, he realized he wanted to paint. He consulted his teacher and exceptionally switched to my class.”

D. “You adopted him somehow, because he was having a hard time.”

N. “Yes, ha ha, later I asked him to be my assistant.”

D. “You have a special bond.”

N. “Yes.”

D. “Before we go, I have to ask you about your stay in my country. How did you end up in Buenos Aires?”

N. “Well, it happened by chance, it was not my decision, I didn’t say ‘I want to go to Argentina.’ I have a friend who was in a residency there and when he came back he told me thousands of fascinating stories about a country that is at the opposite end of the earth, and that’s when I felt like going, eating meat and doing all that he did. Just at that moment the opportunity for the residency came up, I applied and went.”

D. “You were lucky.”

N. “Yes, I knew almost nothing about the country until I was about to travel.”

D. “The first time I came to Japan, in 2017, I didn’t really have much idea either.”

I don’t know of any of the very few references people have in Japan about Argentina, in general. Nobuyuki mentions an anime from the seventies called Haha or Tazunete Sanzenri, which tells the story of a Genovese family that gets separated when the mother decides to emigrate to Argentina due to the economic crisis in Italy. When the main character, Marco Rossi, an 8-year-old boy, stops receiving letters from his mother, he decides to cross the Atlantic looking for her. Together with his pet, a little white monkey, they live exciting adventures traveling through different parts of the country. The anime was born after the success Nippon Animation had with the world-famous Heidi and, before undertaking his own projects with Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki made the drawings of the scenography for Marco, and even traveled to Argentina. I only watched the chapter “Un gaucho llamado Don Carlos,” but all 52 chapters are available in Spanish on YouTube.

D. “What neighborhood did you stay in?”

N. “I was on Iguazú Street… in the southern area, I think.”

D. “Ah, Parque Patricios.”

N. “Speaking of the southern area, I used to take Uber a lot and the second time we took it with my friend, suddenly the driver locked the doors and accelerated, he drove several blocks without stopping, we thought he wanted to kidnap us or something, ha ha, but in fact the driver was passing through an area he thought was dangerous and wanted to protect us.”

D. “Scary!”

N. “In the end nothing happened, but it took us by surprise,” he tells us laughingly about one of his adventures in Buenos Aires.”

In the fall of 2019, Nobuyuki participated for a month in the residency La Ira de Dios. The four artists who shared the open studio in cheLA with Nobuyuki were Manuela Aldabe from Uruguay, María Ossandon from Chile and Yasunori Kawamatsu, his friend from Japan.

D. “Did you exchange any works? Or did you buy anything during your stay?”

N. “I didn’t really have much contact with local artists because when I arrived at the residency almost all the artists were already gone. I did have some contact with an artist from Chile, María Ossandon, but I wasn’t able to share much with the rest.”

D “You also were in touch with the Nikkei community, weren’t you? Interviewing some people for your work.”

N. “Yes, yes, yes, yes. I interviewed six people, they were third or fourth generation Japanese immigrants, all over twenty years old, some of my generation, and the seventh person I interviewed was a very old lady.”

In his works, which at first glance look like colorful watercolors, we see images of faces and bodies that dissolve, outlines that transform into blurred forms; in his videos the image gradually and slowly blurs. Osaki “draws” what he calls the “uncertainty of reality.” He interviews family members, friends or even strangers with whom he comes into contact, talks about his memories and collects information and photographs. But are the memories real?, he wonders. Osaki sees in memories something more than a journey into uncertainty, where fiction and reality are no longer separated by a clear boundary.

D. “A few months later, in November of that year, back in Japan, you made an exhibition at the Parc Gallery in Kyoto29, called Buenos Aires. In the text About opposite twins and coincidence there is a quote attributed to the Russian-American economist Simon Kuznets (1901–1985) that I found interesting: There are four kinds of countries: developed, developing, Japan, and Argentina.”

N. “Yes, I wrote that text for the exhibition. Kuznets is a very famous economist, he won the Nobel Prize in economics.”

D. “At one point you write that Japan went, in a very short time, from being a developing country to a developed country, and that Argentina is the opposite case, you even mention that it was once the ‘Paris of South America.’ What caught my attention is that you see in the Argentine case the future of Japan. It seems to me that it is very unlikely that this will happen, ha ha.”

N. “Look, I wrote that in 2019, it was the feeling I had when I came back home after being in Argentina. It was a feeling of that moment, but now, three years later, with the pandemic and the current state of the economy, I really think it can happen. Rising prices, inflation, the current situation is very bad for us.”

D. “The Argentine case is really very difficult to explain.” (Laughs)

N. “I was fascinated when I went there.”

D. “I can imagine, everything is very different.”

N. “The price of the dollar was constantly changing, it was incredible. I was impressed that, on the one hand, there was the whole situation of economic crisis, but if you went to any nightclub on a Friday night it was full and everyone was dancing happily, full of energy, ha ha. I think that’s a positive thing, despite the context and the difficulties I felt there was hope.”

D. “We are very used to living in a crisis situation.”

N. “Japan at this moment is going down the hill, and the Japanese get depressed when things go wrong, it is very different from your country. In that sense it seems to me that you handle it better, I wish we had more of that attitude here.”

As part of the exhibition, they talked with the artist Fuminori Akiba (associate professor, Nagoya University) and Yasunori Kawamatsu (artist), who were involved in the plot “Osaki and Buenos Aires.” According to the gallery’s website, it seems that the Buenos Aires anecdotes included memories of the Malbec wines they enjoyed every day, and they even recommended looking for them in the konbini stores in Japan. Kanpai!

As it happens after every interview, the house is turned upside down as if a tsunami of works had passed by. At 4 p.m. we say goodbye to Nobuyuki, who has a lot of tidying up to do. Marisa returns by train to Tokyo to be with her family. And I take advantage of the rest of the afternoon to visit the Aichi Triennale30 “Still Alive” and later, return to the capsule.

Interview: Daniela Varone

Photography: Marisa Shimamoto

FOOTNOTES

1Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

2Nobuyuki Osaki: http://www.nobuyuki-osaki.com

3University of the Arts, Kyoto: https://www.kcua.ac.jp/en/

4Futon: instead of copying the dictionary definition I prefer to quote two European writers trying to describe to Western readers what a futon is. The first was a Portuguese missionary who traveled to Japan with the Jesuits and wrote in the 16th century: "The people of Europe sleep on high, on beds or cots; those of Japan sleep low on tatami with which the house is matted. Our mattresses are always spread out on beds; those of Japan are by day always rolled up and hidden where they are not seen." Luis Fróis. Treatise on the contradictions and differences in customs between Europeans and Japanese, 1585. The second was a British journalist, translator, orientalist and writer and he wrote from Japan at the end of the 19th century: "I must here interrupt the story for a few moments, to say a few words about Japanese beds. In a Japanese house, unless one of its tenants is ill, you will never see a bed in the daytime, even if you visit every room and look into every corner. In fact, there are no beds in the Western sense of the term. What the Japanese call a bed has no frame, no springs, no mattress, no sheets and no blankets. It consists only of thick quilts, stuffed, or rather quilted with cotton, which are called futons." Lafcadio Hearn, In the Land of the Gods. Travel accounts of Meiji Japan, 1890-1904. Ediciones el acantilado, Barcelona, 2022.

5Hideo Yoshihara: https://www.moma.org/artists/6511

6Hideki Kimura:https://search.nmao.go.jp/en/detail?cls=col1&pkey=41606&dicCls=d_author&dicDataId=556&detaillnkIdx=0

7Tomohiro Kato: https://www.tomohirokato.com/art-works/mimicking/

8Paul Wunderlich: https://www.moma.org/artists/6463

9National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto: https://www.momak.go.jp/English/

10Ukiyo-e: prints produced by the woodcut printing technique that developed and flourished between 1660 and 1868. They are known as “floating world prints,” an expression that makes reference to the pleasure and theater districts of the Edo period.

11Sumida Hokusai Museum: https://hokusai-museum.jp/?lang=en

12Collaborative system of production of the prints: in general, the authorship of the engravings is attributed to the illustrator, who executed the design of the work. However, at least four people participated in the production, all of them masters in their specialty. The most important actor was the publisher, since he possessed the capital to launch such a production, which required a considerable initial investment. “As a businessman at last, and dealing with an industry with a markedly commercial character, it was the publisher who decided what kind of work to do, with what format, what theme to represent (all this, of course, in relation to what the market demanded), and which illustrator, which engraver and which printer he would hire.” The illustrator would sketch the work with brush and ink on paper and discuss it with the publisher, finally stamping it with his signature and the publisher’s logo. The editor took the final design to the official censor on duty, who determined whether the piece could be published or not, and the official “approval” stamp was stamped on the wooden plates. Then it was on to the carving of the set of plates or blocks in the engraving workshop that was hired. “The engraver, or hori-shi 彫師, would glue the final drawing on its front side to a properly prepared block of cherry wood, using a rice paste. With his fingers he would remove the thick back layers of the paper glued to the wooden block so that it would become transparent. He would then proceed to carve and roughen the wood block. … The printer, or suri-shi 措自帀, was the master who would complete this path. The pigments used in the printing of these woodcuts were of natural origin and had no fat base, so their diluent was almost always water.” Amaury García Rodríguez, Cultura popular y grabado en Japón: Siglos XVII a XIX, 2005. [Popular culture and engraving in Japan: 17th and 19th centuries]

13On the number of copies made of an Ukiyo-e print: the lifespan of a cherrywood plate was considered to be 250 copies, but recent studies indicate that the same block could produce between 3,000 and 10,000 prints. “Of course the final number of copies depended on the demand for the stamp or series in question, and there were cases where it was necessary to re-carve another set of plates. The standard figure suggested at the time would be about 5,000 prints, although again in Fukiokaya’s Diary it is mentioned that ukiyo-e woodcuts were published in units of 1,000 copies.” Amaury García Rodríguez, op. cit.

14Kanae Yamamoto: https://www.artic.edu/artists/60695/yamamoto-kanae

15Christine Greiner, Lecturas del cuerpo en Japón y sus diásporas cognitivas, Zettel Publishing Agency, 2018. [Readings of the body in Japan and its cognitive diasporas].

16Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908), an American Japanologist, art historian, translator, and poet, was one of the many foreign specialists hired by the Japanese government to modernize the country during the Meiji period. He was one of the first serious interpreters of Japanese culture, and his writings and lectures were a reference for Western dealers and collectors of Japanese art. More info: https://www.globalsquaremagazine.com/2017/12/10/ernest-fenollosa-una-vida-entre-oriente-y-occidente/

17Some art dealers of the time were: Siegfried Bing, Hayashi Tadamasa, Matsuki Bunkio and Yamanaka Sadajiro. It's very interesting the print collection of the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright—who sold part of his personal collection to the MET, among other public institutions in the United States.

18Irene Seco Serra, Historia breve de Japón, 2010. [Brief history of Japan].

19Julia Meech. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan. The architect's other passion. Japan Society and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., publishers, 2001.

20Tadanori Yokoo: https://www.moma.org/artists/6502 and see video of his current paintings: https://youtu.be/KnXXYHCcKIw

21Yui Usui: https://yuiusui.com/

22William Kentridge: https://www.kentridge.studio/

23Takeshi Mita: https://mita-takeshi.tumblr.com/

24Naomi Ashida: https://ametsuchi.katalok.ooo/ja

25Yoshinobu Nakagawa: https://nomart.co.jp/gallery/artist/yoshinobu_nakagawa.php

26Shiochi Ida: https://www.moma.org/artists/2795

27Ei-Q or Ei-Kyu or Sugita Hideo (1911–1960) (https://www.momat.go.jp/en/artists/aei001) . He was an avant-garde artist who worked between surrealism and abstraction in painting, photograms and, later, prints and lithographs. During the 1930s he became interested in photography and photograms. In 1936 he published the influential book Nemuri no riyu, which brought him to the forefront of the Japanese avant-garde. He was an influential leader of several artists’ associations in the pre- and post-war periods.

28Masayuki Arai: https://standingpine.jp/en/artists/10

29Exhibition Galley Parc, Kyoto: https://www.galleryparc.com/pdf/2019_pdf/20191122_osaki_pdf/GalleryPARC_Release20191112.pdf

30Aichi Triennale: https://aichitriennale.jp/en/ en esta edición two Argentine artists participated in this edition: Claudia Del Río and Florencia Sadir. See artists: https://aichitriennale.jp/2022/en/artists/index.html. The title “Still Alive” is inspired by the series of the conceptual artist On Kawara, born in Aichi.