FOOTNOTES

1 Tomoki´s website: https://suetomii.wixsite.com/tomoki and his blog: https://ameblo.jp/suetomi1980/entry-10428550119.html?frm=theme

2 Tenugui: rectangle of printed cloth. Its origins date back to the Heian era, 794 to 1192 AD. With unlimited uses, the tenugui became a necessity. Like modern kendokas, samurai wore them under their helmets to protect their foreheads from sweat and, thanks to the lack of seams on the edges, they could also be easily torn if they wanted to use them as a bandage. This seamless edge feature allows for easy wringing and quick drying, hence its use in onsen baths. As the tenugui grew in popularity, it entered the commercial scene and became a promotional product. Businesses, kabuki performers, and sumo athletes sell or give away tenugui adorned with their names, images, or logos. Families acquire tenugui with their kamon or family crests.

3Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

4Koji Kumagai: https://panorama-index.jp/kumagai_yukiharu/

5Ko Soda: www.sodako.com

6Amigo Koike: http://en.tis-home.com/amigos-koike/

7Furuya Usamaru studied sculpture at art school and also became involved with Butoh dance. For a while he worked as a high school art teacher, where he met Tomoki. He made his debut as a manga artist with the groundbreaking Palepoli strip, which was serialized in the legendary avant-garde comics magazine Garo in 1994. Since then, he has published in Japan’s major weekly magazines.

8Astro Boy (published between 1952 and 1968 and adapted into a television series in 1963) is a manga series written and illustrated by Osamu Tezuka (www.tezukaosamu.net). According to the story, set in 2003, the powerful android was created by Doctor Tenma, head of the Ministry of Science, to replace his son Tobio (Atom in Japanese), who died in a car accident. Tenma incorporated Tobio’s memories into Astro and began to treat him as if he were his son. I’m going a bit off topic, but Japan has a long and close relationship with robots, ranging from mechanical karakuri ningyo puppets to Hiroshi Ishiguro’s current geminoids (his own and his five-year-old daughter’s). In line with the link between Doctor Tenma and Astro, the older models of Sony’s Aibo dog-robots, which can no longer be repaired, receive, like the living, funeral rituals at the Kofuku-ji Buddhist temple, accompanied by farewell letters from their caregivers. For animist Shinto, all things have their energy, or what we call soul. See: https://www.abc.es/tecnologia/abci-japon-celebra-entierros-budistas-para-perros-robot-201805031805_noticia.html

9Meriyasu Kataoka: @kataokameriyasu y ver: https://www.japantrends.com/stuffed-animals-designer-makeover-meriyasu-kataoka-fashion-show/

10 Maeriyasu Kataoka´s interview: https://tokion.jp/en/2022/02/03/a-stuffed-toy-artist-meriyasu-kataoka/

11 Kokeshi dolls originate from the cold Tōhoku region, an area of rice farmers and woodworkers. With the leftover wood, the locals began to make these dolls for the little ones. Tōhoku is also a mountainous area full of hot springs (onsen), and soon became a destination to visit and activated the economy of the place. Kokeshi dolls became a souvenir that visitors took home after visiting the hot springs. They are considered objects related to good fortune and the favor of the gods, and are currently produced in different areas of the country, and in some cases through different generations of artisans.

12Kuu Kuu Minami: www.kuu-kuu.com

13The chrysanthemum and the sword. Ruth Benedict, Anthropology Alianza Editorial, 2010. The book was originally published in 1946.

14Izumi Suzuki: https://kokeshka.theshop.jp/items/29431119

15 The Mingei movement arose in Japan in the 1920s, founded by the Japanese writer and philosopher Soetsu Yanagi (1889–1961) in collaboration with ceramists Shoji Hamada (1894-1978) and Kanjiro Kawai (1890-1966). It seeks to enhance the products created by groups of anonymous artisans, as a response to the industrialization of Japanese society due to Western influence and as a reflection on the role of Japanese artistic traditions in a modernizing world. It was inspired by the English Arts & Crafts movement. See: https://mingeikan.or.jp/?lang=en

16Japanese dolls. The fascinating world of ningyō. Alan Scott Pate.

17Karakuri ningyō: https://conoce-japon.com/cultura-2/karakuri-ningyo-los-automatas-japoneses/

18Museum Miraikan: https://www.miraikan.jst.go.jp/en/

19Hiroshi Ishiguro (1963 -) is director of the Intelligent Robotics Laboratory, part of the Department of Systems Innovation, Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University, Japan.

20Seal robot Paro: https://youtu.be/oJq5PQZHU-I

21Japan from a capsule. Robotics, virtuality and sexuality. Julián Varsavsky. Adriana Hidalgo editora, 2019.

22Saeko Takahashi: http://www.saekotakahashi.com/ @bacchiworks_saeko

23Kazuhiro Tanaka: https://www.artsper.com/hk/contemporary-artists/japan/5415/kazuhiko-tanaka

24Laura Ojeda Bär: https://cargocollective.com/laura-o

25Ryoji Arai: www.ryoji-arai.com

26Mamiko Nakamura: @banryoku_mamiko.n

27Wan: @wanwanwonderland

28Takehide Harada: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2017/05/04/films/approaches-50-iwanami-hall-remains-vital-cinema-lovers/

29Iwanami Hall: https://jff.jpf.go.jp/read/news/iwanami-hall/

30Hiroko Watanabe: @hirocoro43 / http://hiroko-watanabe.com/

31In this blog post we can see the production process of Tomoki’s calendar in the city of Kanazawa: https://ameblo.jp/suetomi1980/entry-12771292427.html

32Mariela Scafati: @scafatiscafati

33Ritsuko Ozeki: @littleko316 and also see: https://www.ritsukoozeki.com/

34@pe_isgood. In the account description it says: Hand embroidery works of illustration by Tomoki Watanabe.

35 Mori Michi Fair: www.morimichiichiba.jp

36 Ana Clara Soler www.anaclarasoler.com.ar

“We like to go see exhibitions and we buy some works together”

Tomoki Watanabe

Tomoki (1980) tells us about his life, and also his work, in a blog called Pepepe by Tomoki Watanabe. Everyday life here and there1. I love that, instead of publishing a CV with lists of exhibitions, grants and awards, he decides to write in his blog a sort of biography that works as a personal diary. The history that he writes, in different entries divided by categories, is extensive and abounds in curious details. He began writing his first diary at the age of twenty-one, and by 2017, that is, fifteen years later, we know that he reached number 125.

In addition to being a visual artist, Tomoki writes poems, plays the piano, records a CD with improvisations, is a movie lover, an illustrator of books, makes fanzines, produces a calendar and a tenugui2 a year, makes tableware in collaboration with ceramists, is a runner, plays soccer, has his clothing brand [Pe_], teaches art classes and organizes workshops.

This was the first interview we did in Tokyo for Artists’ Collections. We met for the first time with the work team at Musashi no mori coffee, a huge coffee shop near the artist’s house in the Kichijōji area. Marisa Shimamoto3, the project’s photographer, arrives first, and she recognizes me right away, since I’m the only gaijin in the room. As soon as she approaches the table, she has to assist me with something that the waitress tries to explain to me with great patience.

“What you ordered is going to take twenty minutes,” she tells me in perfect English and with a friendly tone. The fluffy Japanese pancakes are well worth the wait.

Half an hour later, arrives Atsushi Kugue, the translator (English-Japanese) that I hired for this first test. We walk a few blocks together, and soon after, we’re ringing the doorbell at Tomoki and his wife Natsumi’s apartment. He opens the door for us with a warm smile, dressed all in pink.

We filled the genkan space with shoes, tripods and other photographic accessories and we began with the interview. As I write this, I notice in the photo that they both have their shoes facing the door (easier to put on when leaving) and that my white Adidas are not only in the wrong position, but are even outside the established area, inside the house.

Tomoki attended a high school, in his own words, “quite liberal,” in the Kichijōji area, a neighborhood of the city of Musashino, in western Tokyo. In the late 1990s, while spending his afternoons playing on the soccer team, he began painting and taking photos.

D. “In your blog you mention that, when you were a teenager, you used to go to the Inokashira park, which is near your house, to draw portraits (it is a huge park full of trees, with ponds, bridges, a zoo and even a running track). So, this morning I stopped by to visit it before coming here.”

T. “Oh, yes?,” he says, surprised.

D. “What shocked me the most at the entrance was the sound of cicadas and crows, and some walking trails of damp black earth. I wonder how those portraits that you did back then were like. Did you ask people to pose?”

T. “I drew people who went to the park, but, at that time, it was not allowed to charge for that. It was a "gray area" let's say, so they would take the drawing as a gift. I used to sit on a bench and people just came to me.”—to describe the encounter, he uses the word nanpa, which in Japanese culture is a type of flirtation and seduction popular among young people—. “Now you can charge if you pay for the right to use the park. That encounter with people was very important to me, it did me good.”

D. “You seem to be very sociable, because I see in your social media that you publish many photos with different people.”

T. “Actually I’m not. I have two faces,” —Tomoki is an attentive and warm person, with a particular sense of humor, more subtle than direct. He manages to walk that fine line and his answers always surprise.

D. “It is a facade then.” —I say, following his game.

In the corridor that goes from the front door to the living room there are a series of shelves and bookshelves with small works of all kinds. Near the door there is a carefully organized sector. A painting by Tomoki with pink, yellow and red colors, which I immediately recognize, dominates the scene. There are a few more of his works: two "flower-men" and a ceramic plate with birds flying in circles. They coexist with a very simple portrait drawn on a piece of paper, with a few words in Russian, and some small figures posing in a row: a four-legged animal, a triangular figure with the word welcome on its chest, and a manekineko.

T. “Why don’t we pretend that this is someone else’s house, and that this is his collection? Because except for three works, the rest are all mine,” he says laughing. “I have this piece made of paper and clay, it’s by an artist called Koji Kumagai (1978 -)”4, he tells me while holding a small animal figure, trying to remember what material it’s made of. “He is an artist who works with ceramics and other techniques. I don’t remember if it was a paper or a cloth roll, but when you bury it, it hardens.”

D. “How did you get it?”

T. “I bought it at his exhibition. I have two works by the same artist; one is made of sand, mud, if you put it in water it melts.”

Each of my questions open a dialogue in Japanese between Tomoki, his wife and the translator, which I enjoy listening to, even if I don’t understand it. I only recognize that they say the word manekineko, and I repeat it out loud, as if I were part of the conversation too.

D. “And this is the typical bowl at the entrance of houses to leave the keys.”

T. “Yes, yes. Made by Soda-san (Ko Soda)5, it’s made of leather.”

D. “And who did that portrait? I ask, pointing to the small drawing with Russian words on it.

T. “It’s from a Russian girl I met on the Trans-Siberian train.”

D. “Ah, yes, I read about that trip on your blog.”

Of the network of routes that covers 10,000 kilometers and crosses seven time zones, Tomoki takes the section that goes from the Russian port city, Vladivostok, near the border with China and North Korea, to Moscow. The journey takes a week and, from there, he visits three countries in the Balkans: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Unlike the Japanese Shinkansen, which reaches 320 kilometers per hour, this train is not for eager travelers, since the average speed is 60 kilometers per hour. The drawing, almost childlike, seems to be a portrait of Tomoki, but he doesn’t tell me any more details.

UA few meters further on, hanging inside the bathroom, there is another work with a text in Russian that says: “When eyes go away, hearts come closer.”

T. “It is a Russian expression. I bought it there, but I think the fabric is not Russian. I looked for a text that would fit well with the fabric, it’s hand embroidery. Maybe it wasn’t Russian, now I’m not sure...”

D. “Like the embroidery on your t-shirt, it’s so neat that it looks like it was done by a machine,” I tell him while I point to the yellow embroidery that runs through the pink fabric.

T. “Nat-chan made it,” he says, pointing to his wife. Months after the interview, I discovered that chan is a suffix with an affectionate tone that the Japanese use after the name of someone very close. During the interview I imagined that it was her real name.

D. “You? Ah, that’s amazing,” the five of us say in chorus in the hallway. “Tell me about this other painting with white flowers.”

T. “This is from Amigo Koike6, he is an illustrator.”

D. “Amigo, in Spanish, is his name?”

T. “Yes, yes, yes…”—he says: so, so, so—“it’s a nickname. It was inspired by the greeting”—in Japan, amigo sounds like hello, it is used as a greeting—.“I also bought it at his exhibition. Amigo-san is the president of an association of illustrators.”

D. “I get the impression that you buy a lot of art.”

T. “Well, we like to go see exhibitions and we buy some works together. It’s something we like to do. But more than fifty percent of what you’re going to see today was bought by Nat-chan.”

As I look around the interior of the apartment, which is much larger and less conventional than I imagined, I remember the houses and buildings that I saw earlier on the way to the cafeteria.

D. “From what I read on your blog, you always lived in this area, right? You moved back to your mom’s house a few times, but always in this area.”

T. “How do you know that?”

D. “You wrote it! And Google Maps. What do you like about this area? It is very quiet, an area of houses.”

T. “I’m stuck on the Chūō Line,” he says, referring to the fast train line. The railway network is so important that, on the pages of local real estate, you can search for apartments by filtering the train line you prefer. “I feel like I have to stay in this zone, it’s something spiritual. On the other hand, in the future I would like to live abroad. I don’t feel any reason to leave this area, but if the possibility arises of living in a new place, I could do so.”

Tomoki is a self-taught artist. In Japan, to study art at a private university, in addition to having money or taking out a student loan, it’s mandatory to pass a rigorous admission exam. In 1998 Tomoki enrolled in the Musashino Art Academy preparatory course. The following year he finished high school and failed the admission exam to the historic Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai), which only one out of forty students manages to enter every year according to what another artist told me. At this moment the real adventure begins for Tomoki. He decides to go on a trip and in an hour he has everything set up: he takes a sleeping bag and his drawing kit. He travels his country from one end to the other "hitchhiking" and gets into more than two hundred cars between Aomori Prefecture and the island of Okinawa.. By 2011, he has counted about three thousand portraits. Later he settles six months in Adelaide, Australia. In his blog he says that he drew almost every day of his stay there.

Tomoki is a self-taught artist. In Japan, to study art at a private university, in addition to having money or taking out a student loan, it’s mandatory to pass a rigorous admission exam. In 1998 Tomoki enrolled in the Musashino Art Academy preparatory course. The following year he finished high school and failed the admission exam to the historic Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai), which only one out of forty students manages to enter every year according to what another artist told me. At this moment the real adventure begins for Tomoki. He decides to go on a trip and in an hour he has everything set up: he takes a sleeping bag and his drawing kit. He travels his country from one end to the other "hitchhiking" and gets into more than two hundred cars between Aomori Prefecture and the island of Okinawa.. By 2011, he has counted about three thousand portraits. Later he settles six months in Adelaide, Australia. In his blog he says that he drew almost every day of his stay there.

D. “I also read that during those years you were an assistant to the manga artists Usamaru Furuya7. How was that experience?”

T. “Usamaru was an art teacher at the high school I attended and became a professional artist while he was working there.”

D. “What did you do for him?”

T. "I was his first assistant, I was in charge of the backgrounds of the stories, I never painted characters. He works with a technique called trace, it doesn’t take much skill to use it.”

D. “Did you like that job?”

T. “Let’s say manga is something that I wouldn’t choose. He wanted me to stay and live and work in his house, but that didn’t interest me, so I quit. Usamaru draws all day, except for the thirty minutes that he goes for a walk. His goal was to surpass the famous Osamu Tezuka (1928–1989)”—on this side of the world, we know him as the creator of the android child Astro Boy8 —, “it was very hard work and at one point I got tired.”

We go back to the collection. On a low bookshelf in the hallway, packed with books and diaries, there are various small objects and dolls.

T. “I have these two works by Meriyasu Kataoka (1985 -),”9 he says, pointing to two stuffed dolls with accessories.

D. “Ah, yes, she is quite famous, isn’t she?”

T. “Well, I don’t know if she’s famous, but she has thirty thousand followers on Instagram, and she exhibits outside of Japan as well.

D. “I loved the exhibition ‘Doll house’, when she celebrated the 10° anniversary of her career at the Yokohama Doll Museum, in which she turned the museum's doll collection into stuffed animals. Does this pair of dolls represent the two of you?”

T. “No, it’s not us, it’s Meriyasu and her husband. She is a very good friend of mine. I won them by playing ‘rock, paper, scissors’ at her wedding. I was the master of ceremony for the wedding’s afterparty.”

D. “I must confess that, a year ago when you sent me some pictures of your collection and I saw Meriyasu's stuffed animals, I thought, ‘what is this?’ I was very surprised, and I had to investigate a bit to understand. Then I also remembered that in Japan it´s common to see in the street a surprising number of adults, not only young people, carrying little stuffed toy keychains in their bags. And in an interview Meriyasu says about it: “Even middle-aged men attach them to their backpacks. I think everyone is really just holding back from a life with stuffed toys. (laughs) Stuffed toys say things that you can’t say yourself, and even people who find it difficult to make conversation can feel at ease with a stuffed toy on their lap, as if it compensates for their weaknesses. Stuffed toys may not be necessary for mentally strong people, but when I’m a bit anxious, having a stuffed toy nearby puts me at ease. It’s really amazing that even though they look cute, they’re also dependable. It reminds me that they have an invisible power”.10

T. “This other one is a piece that we created together as ‘Adadel’. I made the ceramic body, and she made the stuffed head,” he says, holding up a free version of a kokeshi doll11.

D. “I was wondering what Adadel was.”

T. “Adadel is an accident” (laughs). When he says funny things like that, he always makes it serious, as if concentrated.

D. “But what is it? A brand?”

T. “It is Meriyasu and I doing art works together. It is a common project that we have had for years, since 2013. We would like to do it more often, but now we are both very busy.”

D. “I see. We also have this small terracotta image, with a little face.”

T. “It belongs to an older man, Kuu Kuu Minami (1950 -)12. He made more than fifteen hundred works of different sizes. I also bought this one at his exhibition,” he tells me while we look at a book of his works with hundreds of dolls, barely sketched but with little faces. “He is also the owner of a very popular curry shop in Kichijōji, where I worked ten or fifteen years ago.”

D. “Ah, wow. Did you buy it?”

T. “Yes, out of obligation," —he jokes and we all laugh. He uses the word ‘giri’, which translates as "duty" or "social obligation" and refers to the gratitude people must show to others. His humor allows us to peek into some key concepts of this society. ‘Giri’, according to the Japanese proverb, "is the hardest thing to bear,"13 and there is a lot of literature on the subject—. Well, I don’t know, from what I see in some foreign films, people buy because they fall in love with a work, but in my case it’s not like that."

M. “So, you don’t have works that you have fallen in love with?”

T. “Maybe Nat-chan does. When I go to an exhibition of a friend or colleague, somehow I feel that I can't go back empty-handed, I have to buy something. I buy the work because I like it, but it is also a form of recognition of their work.”

D. “You have to go to the exhibitions with money, then.”

T. “I always buy the smallest things ha ha.”

On the same shelf there is also a doll by Izumi Suzuki made with various materials: cloth, paper, stone.12 On the same shelf there is also a doll by Izumi Suzuki14 made with various materials: cloth, paper, stone.

D. “Are you friends?”

T. “We know each other.”

D. “And those other dolls with curly skirts, where are they from?”

T. “They are mingei15, handcrafts from the island of Hokkaido, just like this little bear. And these things next to it are seeds that I brought from Thailand, I found them in the ground. This little leather book is also by Soda-san, by the same artist who made the bowl at the entrance. It’s one of Nat-chan’s favorites. His son did the drawing.”

In the artists' collections it is common to find handicrafts, masks, small animals and objects made of ceramics, and in Tomoki and Natsumi´s collection predominate small figures, dolls, stuffed animals, various objects with faces. Japan has a long tradition (and fascination) with dolls, and the antique ones are collection pieces16. We find ningyō associated with festivals (such as the Hina Matsuri or the Tango-no-Sekku to pray for the healthy growth of girls and boys), there are display dolls for adults, there are those used by children to play, the theatrical ones (puppets and marionettes) and the incredible karakuri ningyō17 (mechanical dolls) that were used, centuries ago, for home entertainment. I wonder if it will be possible to draw a line, however erratic and wavy, between these stuffed animals, the kokeshi dolls, the mechanical puppets and, down the road, the androids on display at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation18. To see them live, that same week I decide to mingle with students from local schools and visit the robots and androids of the eccentric engineer Hiroshi Ishiguro19 (on the way I cross paths with a twenty-meter tall Gundam robot). Once in the Miraikan, I wait my turn, and reach through the acrylic dome to caress the gray stuffed animal (already a bit hard) of the therapeutic robot seal Paro20, which reacts by making a tender face at me. These creations fascinate and discomfort me in equal parts, but I understand that for some people, contact with a robot may be more relaxed and without protocols: "Where a Westerner is paralyzed in front of a humanoid, a Japanese person is uninhibited.”21

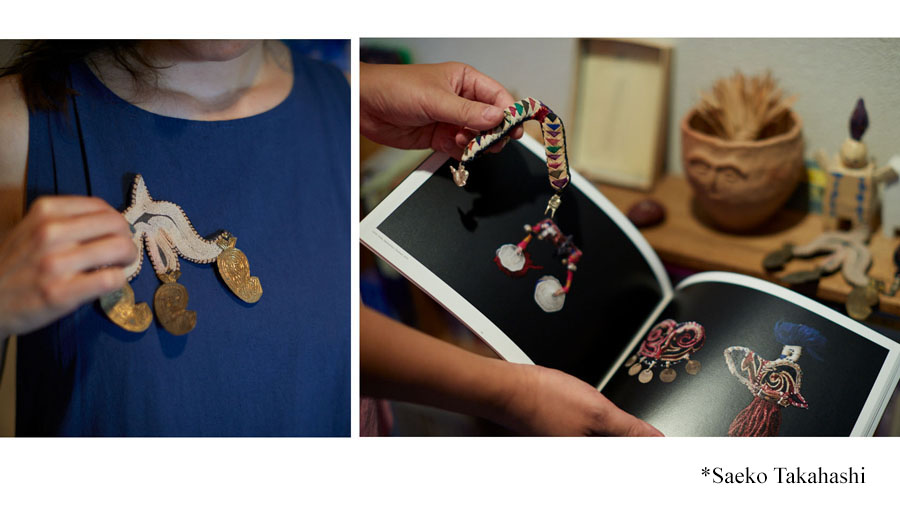

D.—“Some of these pieces remind me of ex-votos.” I say holding up another object from the same bookshelf in the hallway.

T. “These pieces are by Saeko Takahashi , an artist who is my age. They are brooches, they are called Acchi Cocchi Bacchi. Acchi Cocchi means "Here and there", and she travels all over the world, but mostly in Asia, Thailand, Afghanistan, Morocco, India, and she buys different materials and then works on the pieces in Japan.”

D. “Ohhh, I see. Do you wear them?”

T. “I don’t, but Nat-chan does.”

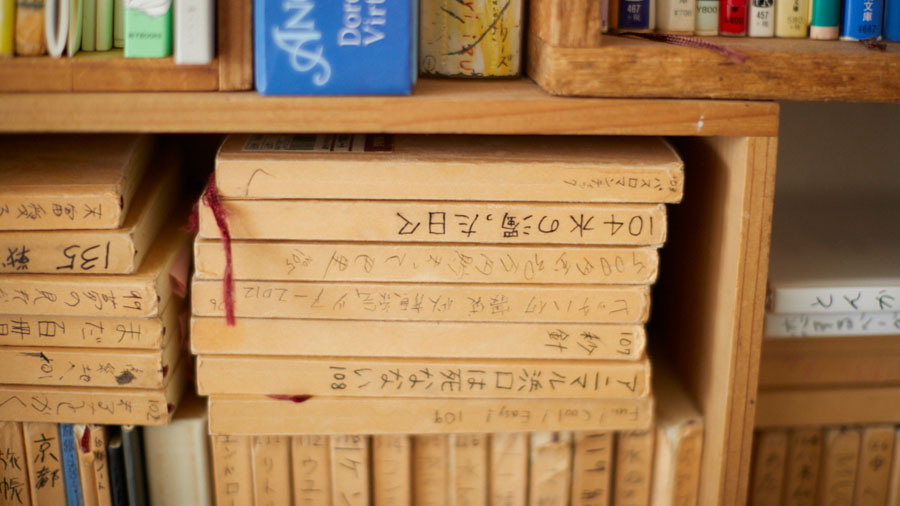

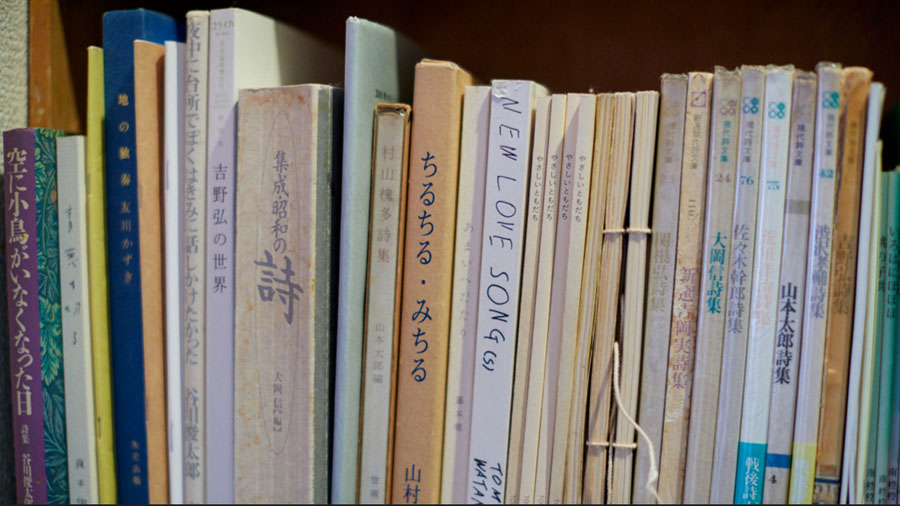

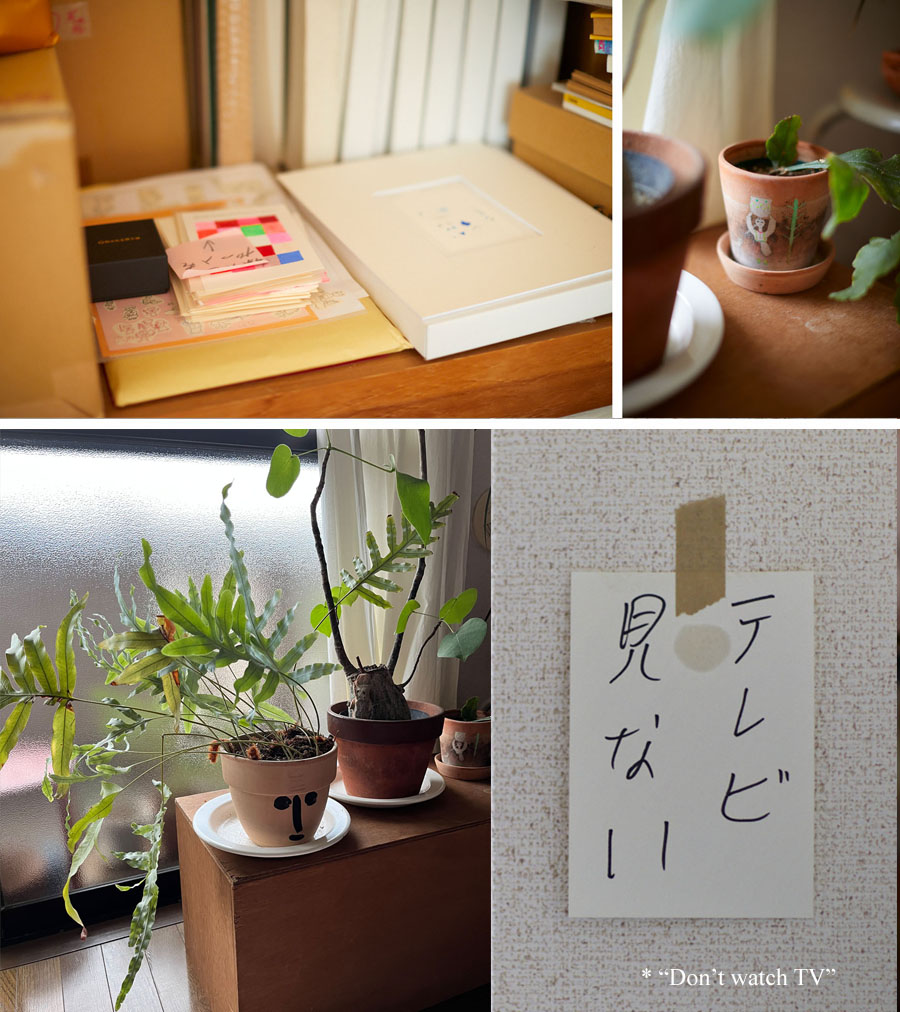

In the same bookshelf there is a section of books, but also several shelves of beige diaries with kanjis on the spine, numbered and ordered, 104, 105, 106…

D. “These are your diaries, right? How many do you have?”

T. “One hundred and forty, more or less, they are Muji notebooks.”

D. “Do you write every day?”

T. “Not every day, sometimes I don’t write anything for two months… I write, I draw.”

D. “I would like to know about the zine you made: “Yasachi Tomodachi…” I read that name with difficulty in my notes, thinking that maybe it is an invented Tomoki’s nickname.

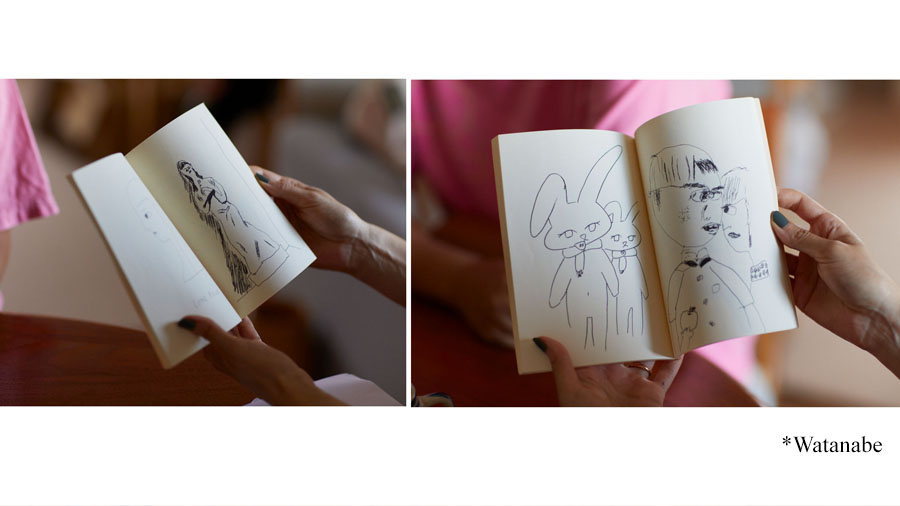

T. “Oh yes, it is the title of the publication, it means ‘kind friend.’ It’s based on my diaries, it has some drawings from about fifteen diaries. A publisher did it, a gallery owner selected the drawings, and I chose the title.”

A white book with drawings also appears, and we pause to check it.

T. “This is about Nat-chan.” Crouched down on the hallway floor, Marisa turns the pages of the book, while she translates it for me at the same time. The characters are Nat-chan and Tomoki, the head is a simple circle, and the body is a series of sticks. One character approaches the other and begins to repeat her name... “Nat-chan, Nat-chan, Nat-chaaaaaan,” until the last letter of chan gets into the head-circle of the other character.

T. “Before I got married I used to be quite alone, but the marriage changed that.”

D. “You got married in 2014, right?”

T. “Yes, I’m surprised that you know that.”

D. “What I don’t know is how you met.”

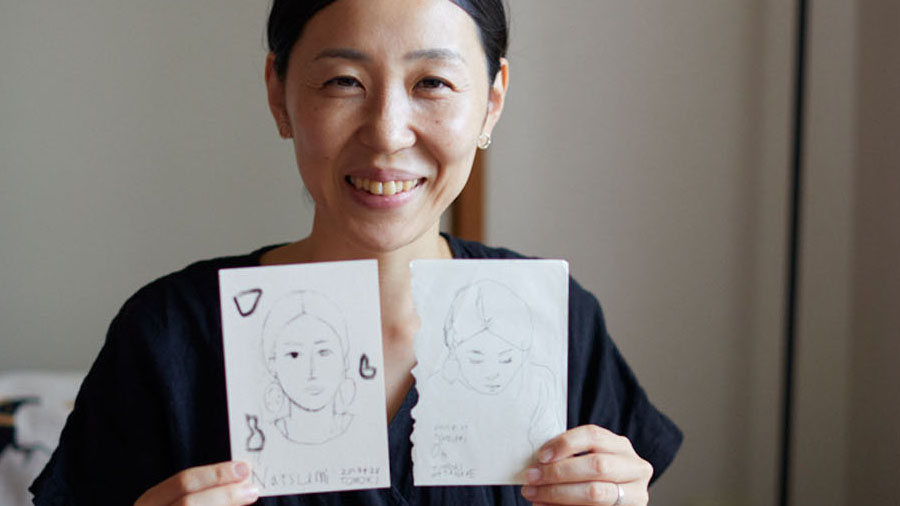

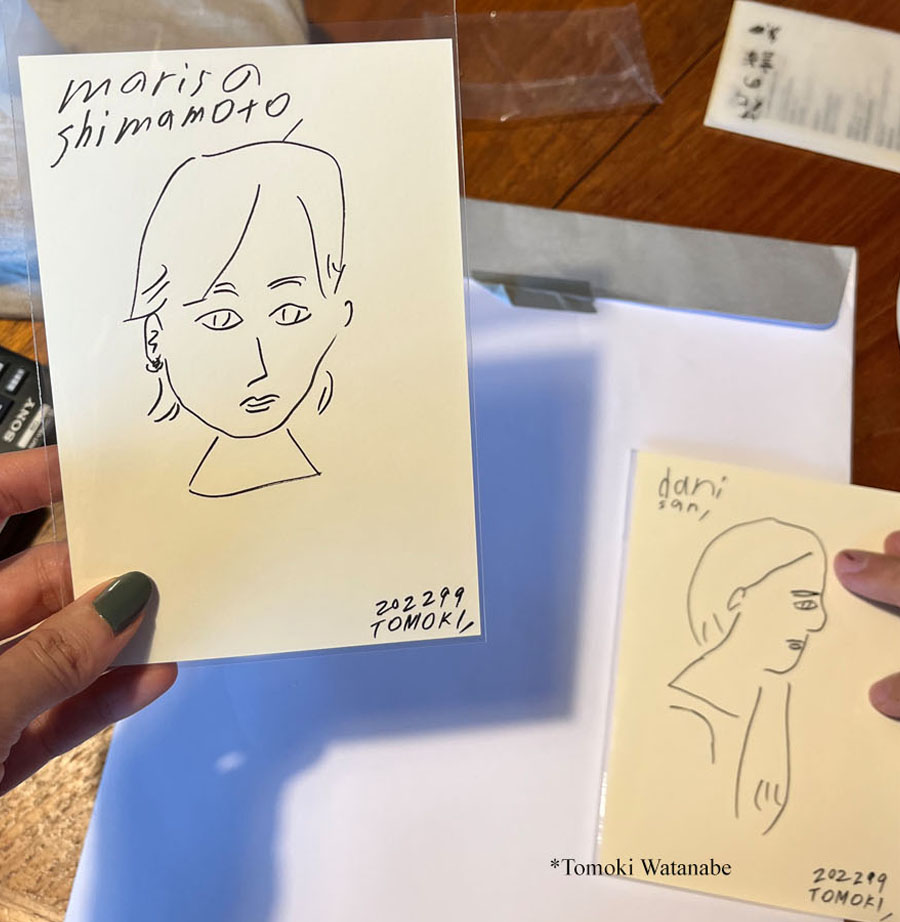

T. “We met at an event, I was doing portraits. It was quite a big event, imagine a space three times the size of this room. When she entered the room, I saw her profile and I felt that I wanted to marry her. It was love at first sight.”

D. “I thought so,” we all laugh, but Natsumi laughs a little more. “Do you have that portrait that you did when you first met?”

N. “Yes, I have it, can I show it?”

T. “Yes, but you’re going to see that it doesn’t look alike, ha ha!”

Natsumi goes to another room to look for the two drawings from that day, and brings them. Marisa takes some photos of her on the couch while we continue the conversation. Natsumi’s voice hardly appears in the audio, but she is present throughout the interview with a lot of attention. She is seen leaning out in some photos, Tomoki consults her on many things, she brings us books, works, offers us tea, she participates in her own way. She has a warm smile, and her eyes smile too.

D. “If it’s ok, we can sit down for a while. I have some general questions about collecting to ask you, and some more personal ones that have to do with your life and your work. For example: when does your collection begin, more or less?”

T. “Well, I have no conscious intention to collect really.”

D. “Yes, I understand. Almost none of the artists I interviewed consider themselves collectors.”

T. “Ha ha ha! I don’t remember which was the first work, perhaps the terracotta one is the oldest. But the first one I bought must have been ten years or so ago.”

D. “Do you think that the pieces in your collection influence your work in some way?”

T. “I think not.”

D. “Perhaps unconsciously.”

T. “Yes, that’s possible. When I work on my art I try not to think about anything, I just start drawing, writing, painting or whatever. I consider the relationship with the gallery or with the person who commissions me the work, that seems important to me. But I try to have a blank mind when I work, and I start from scratch. I look for my hand to flow, expand, for a pleasant shape to emerge; perhaps things come from the unconscious. A bit of a Zen way, and I try not to force it. This is very personal, but I care about the place where I am going to show, also the link with the gallery owner. If I have a project I work; if not, I don’t. Let’s say I don’t produce work if I don’t have a deadline.”

D. “You try to have an empty mind.”

T. “I don’t even want to think about it, I want to be totally free. Sometimes I think about how I can get rid of any previous idea, that’s what I’m looking for with my drawing. At school I did a lot of drawings in class, because I got bored. They arose from that moment of boredom. And then people began to recognize my work and that makes me keep working. Maybe one day I’ll start doing it of my own free will.”

Between questions, we have some tea while sitting at the table and we eat some cookies that I bought for them the day before in the oldest department store in Japan, Mitsukoshi. When I mention the store, they make jokes in Japanese that I don’t understand. I entered the building by chance, following directions from Google Maps, while looking for a place to have lunch, which happened to be on the 9th floor of the large building in Ginza. In Japan, some businesses can be hundreds of years old. The family business that gives rise to the current Mitsukoshi was founded in 1673 and was dedicated to the door-to-door sale of kimonos. Ten years later, they set up a store near the Nihonbashi Bridge, the most important shopping area in the Edo period (1603-1868). A few centuries later, the current building has an entire basement dedicated to the sale of teas, wagashi and other sweets, to lose yourself in for hours.

D. “I bought these cookies because I wanted to try them,” I say as I open the box, and at the same time I realize that there is nothing Japanese about them, except for the individual wrapping. “Let me see what other questions I have in my notes. You were also an assistant to Kazuhiro Tanaka (1953 -)23, who is an artist and an architect, right?”

T. “Tanaka is quite famous, he is in some collections in Europe and in other countries.”

D. “How did you assist him?”

T. “I helped him with his works, I made his characters with clay.”

D. “Did that work influence you in any way?"

T. “Honestly, I never asked myself. Do you think that other artists do have some influence of that kind?”

D. “Yes, I do. I ask because, in several interviews done in Argentina, artists talk about this type of ties with other artists or with other works. Influence, inspiration, admiration. Laura Ojeda Bär24, for example, worked as an assistant to other artists, and she says that seeing the way others work helped her think differently. That exercise of seeing how others do it can be interesting too.”

T. “I think that doesn’t happen to me. At least I am not aware of having been influenced by these artists for whom I worked.”

D. “Changing the subject, in your blog you talk a lot about sports and soccer. Do you have a soccer team with other artists?” I ask him as we look at a photo he posted on Instagram.

T. “No, I barely know most of them, but there is an artist in the group: Ryoji Arai (1956 -)25. He is a very famous children’s books illustrator. A few years ago, he won the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award in Europe and received about twenty million yen (115,000 dollars).”

D. “Is he this one, the gray-haired one?”

T. “Yes, he became very famous, he is doing very well.”

D. “So, I wonder, what is Pepepe?”

T. “The first time I used Pepepe was as a title for my blog, which I have had for fifteen years. The kanji for my name Tomoki Watanabe is very complex, it has many strokes (渡邉 知樹). I wasn’t looking to replace my name, but wanted it to be Pepepe by Tomoki Watanabe. Now I’m going to get a little deeper. Keeping my name is proof that I accept my father’s last name, and I have mixed feelings about that, I don’t really like it. I want to continue using it, but I also use the nickname Pepepe.

D. “But it doesn’t mean anything, does it?”

T. “No, no, it doesn’t mean anything. I think I could answer ‘no’ to almost all of your questions,” he says, and everyone at the table laughs. “I got serious to explain something very simple ha ha.”

During the talk I see another work, sitting on the edge of a tableware cabinet, which I recognize. It’s a pair of crossed legs, with pants, made of fabric. Natsumi takes them and gives us a demonstration. She places the work over her eyes, with her head back to hold it.

D. “Let’s talk about that work, which I love.”

A. “Oh, it scares me.”

T. “Eye pillow,” Tomoki says in English, and we all burst into laughter, and tenderness at the same time.

D. “Is it a work of art or is it really an eye pillow?”

T. “It’s a work by Mamiko Nakamura (1982 -)26, she thinks it’s funny that it can be used in this way too. Being a work of art, she finds it fun to call it an eye pillow.”

D. “Oh, you can change the pants, it’s to die for.”

T. “A few weeks ago she came to our home for dinner. She is a good friend. She loves the Stranger Things show and we only talked about it.”

D. “I saw that she also designs garments; some are wearable, like some dress collars.”

T. “She mainly creates clothes; she is a dressmaker.”

Little works by Mamiko keep coming to the table. While we talk, Natsumi quietly brings them over and leaves them on the table.

D. “I love this story, guys. Are you having a good time? I do, but let me know when you want me to go, ha ha!”

T. “Yes, yes, ha ha ha!”

D. “Maybe one-half hour more and we’ll be gone,” I say to the translator, with whom we had agreed on an hour and a half and now we’re going for two.

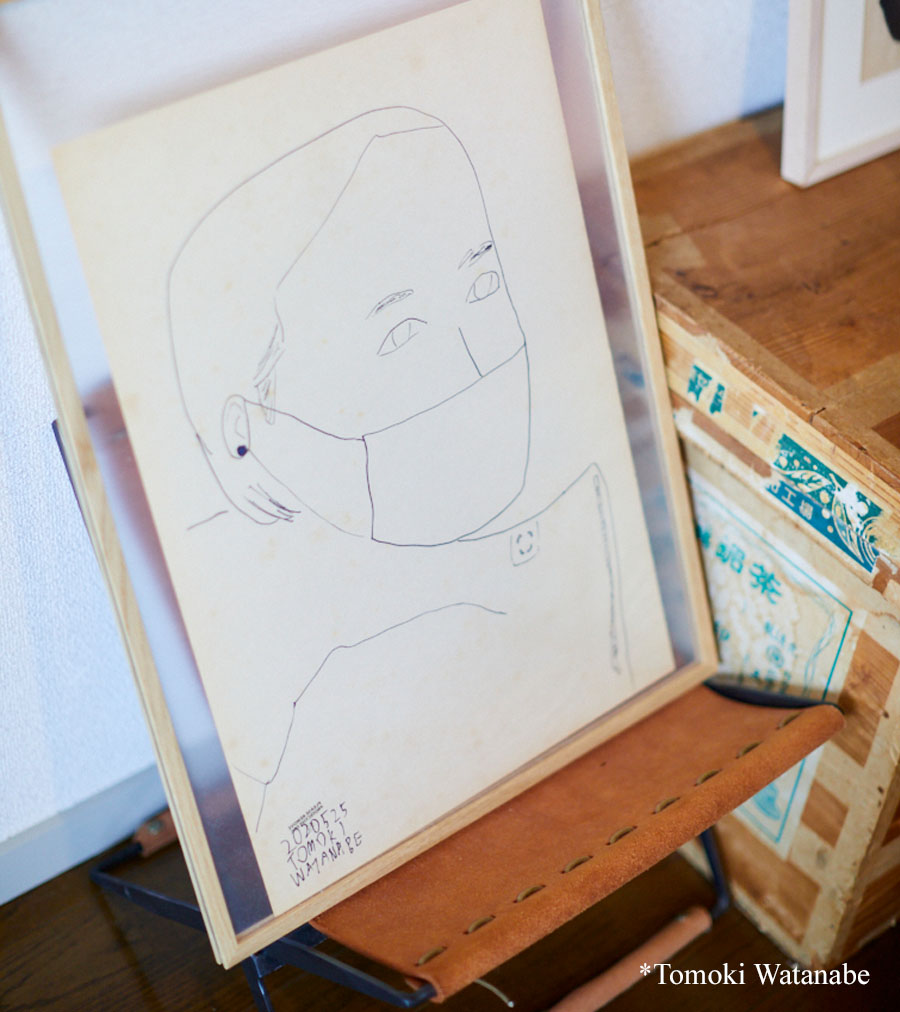

We stand up to check the other rooms. In the same corridor that we already passed, but over the bedroom entrance, hangs a very simple portrait of a woman.

D. “And this is an old portrait that you did, right? Or is it not that old?”

T. “In fact, it’s a portrait of Nat-chan.”

A. “But they don’t look alike.”

T. “I did it when she was busy, and at that moment her soul had abandoned her —he jokes.”

There are works of art in every corner of the apartment. They invite us to check every room in the house, including the bedroom. On the nightstand there is a lamp that catches our attention.

T. “It was made by a Japanese woman, Wan-chan27 , it’s a lamp with a wooden base and a printed fabric, she really likes dogs” (onomatopoeias abound in Japanese language, and the dogs’ barking sounds like wan wan wan). “At the beginning, she was a wood craftswoman.”

D. “And what about that big fabric on the bed?”

There is a short debate with Natsumi about it.

T. “It’s from a second-hand store. We don’t really know where it is from, it seems from abroad. Maybe it’s from Mexico?”

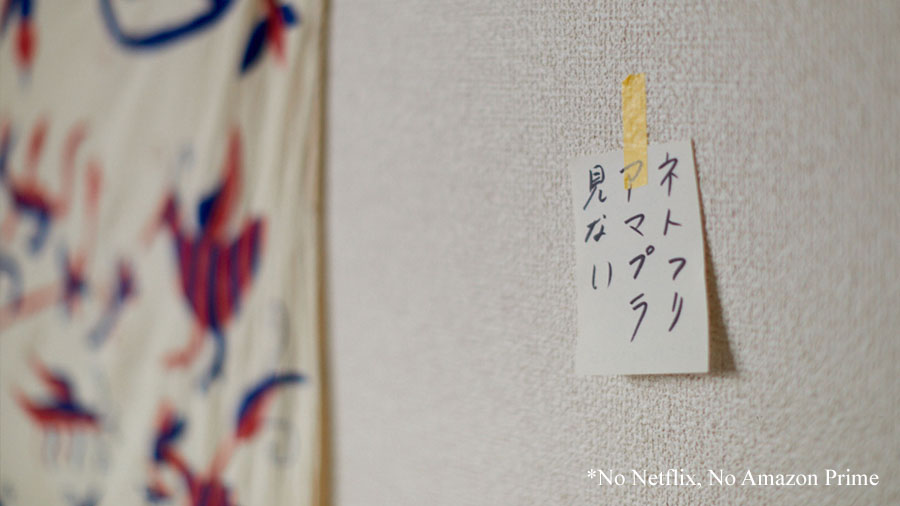

D. “Mm, I don’t know, it looks like pre-Columbian designs. But I don’t really know. And that little note next to it, taped to the wall, what does it say?”

T. “No Netflix, no Amazon Prime,” they burst out laughing. “It’s a message I wrote for both of us. It’s taken from the Tower Records slogan: No music, no life.”

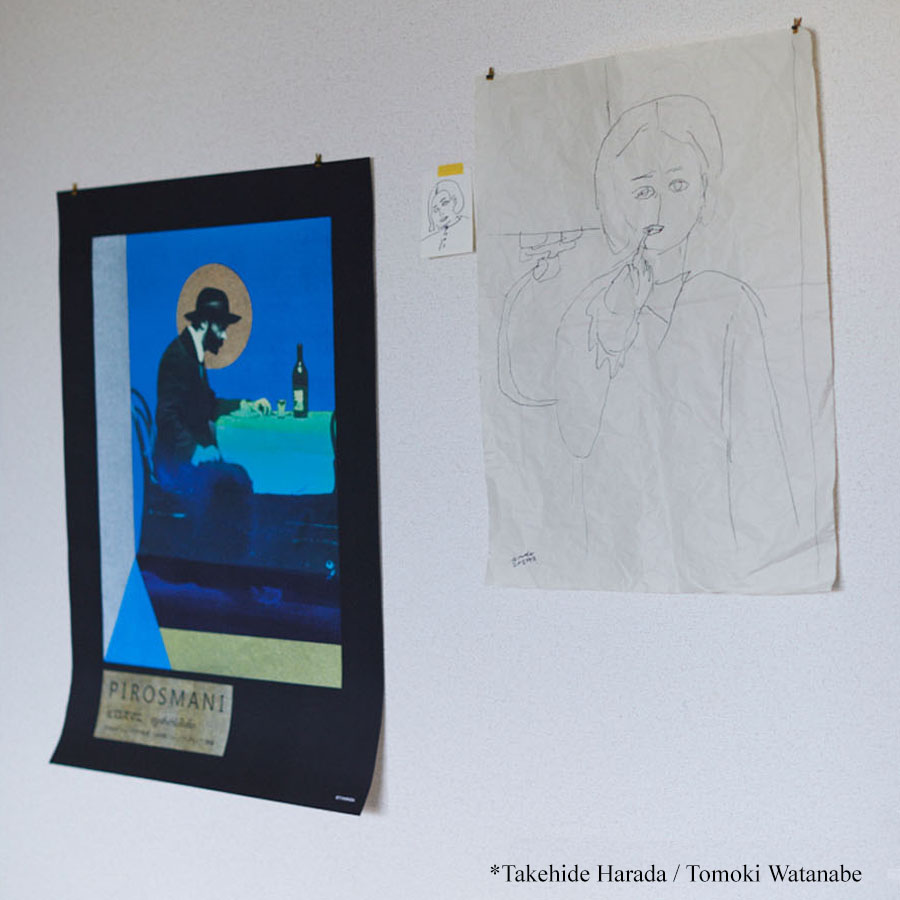

On the wall, at one side of the bed, there is a poster and two more portraits of Natsumi.

D. “Tell me about this poster?”

T. “It is from a film about an artist that passed away, Niko Pirosmani (1862–1918), from Georgia, which at that time belonged to the Soviet Union. The artist Takehide Harada28, who is an illustrator, worked with the image of the movie poster. Harada worked at the Iwanami Hall29 movie theater, which recently closed; Georgian and international cinema was shown there.”

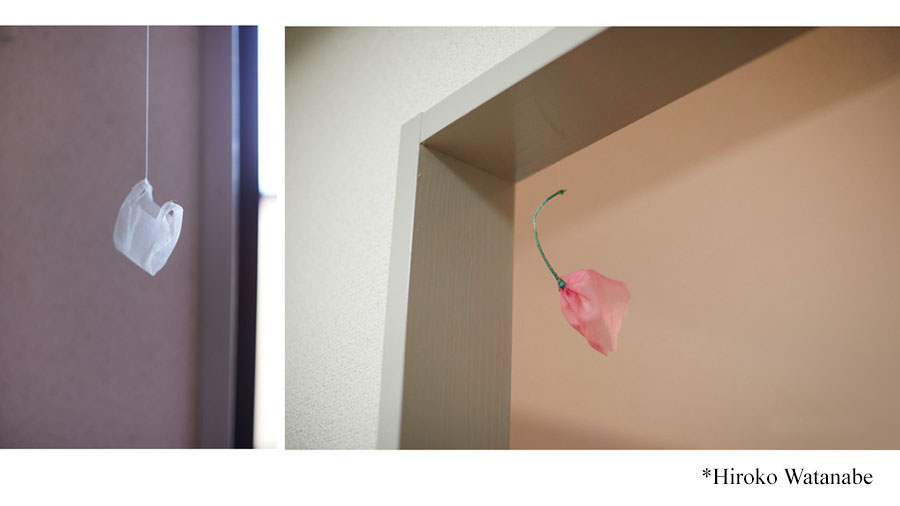

On the curtain rail I see a very small work by Hiroko Watanabe (1981 -)30, it’s a transparent bag that hangs over the window. There was a ball inside it that's missing. They don’t know where it is. Maybe it was blown away by the wind, because the window was open. They also have more works by this artist: a little duster, a flower and a doll.

T. “I have a lot of her work. She has a gallery in Yoyogi Uehara called the April Shop, where they do art exhibitions. I showed there a couple of years ago. She attaches great importance to the installation of the works when she does the exhibitions.”

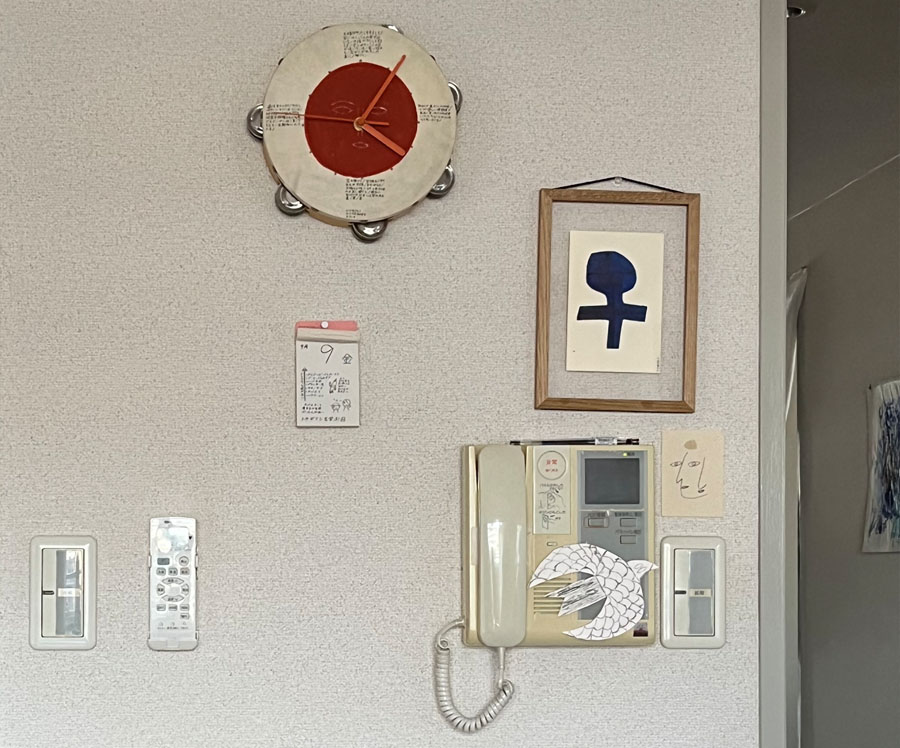

Back in the living room, I see a small calendar hanging on the kitchen’s wall (which marks September 9th), and above it a tambourine-clock, both made by Tomoki. The two things that can’t be missing in a Japanese house.

D. “I imagined it much bigger! I imagined it was at least double the size. Is the one for next year ready?”

T. “I just finished it today, because tomorrow I’m going to a residence in the mountains for two weeks.”

D. “We need to have them. We want to buy it!”

T. “It won’t be ready until November, at least.”

D. “Let’s see the original drafts.”

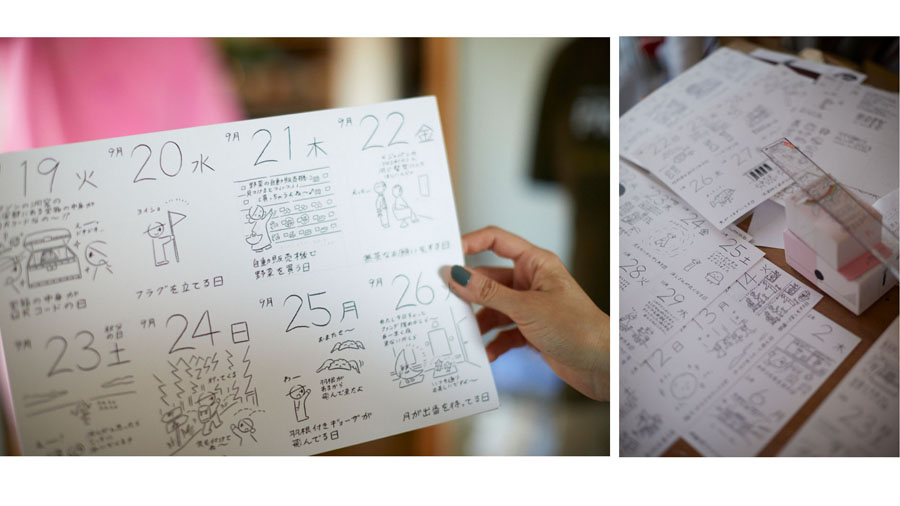

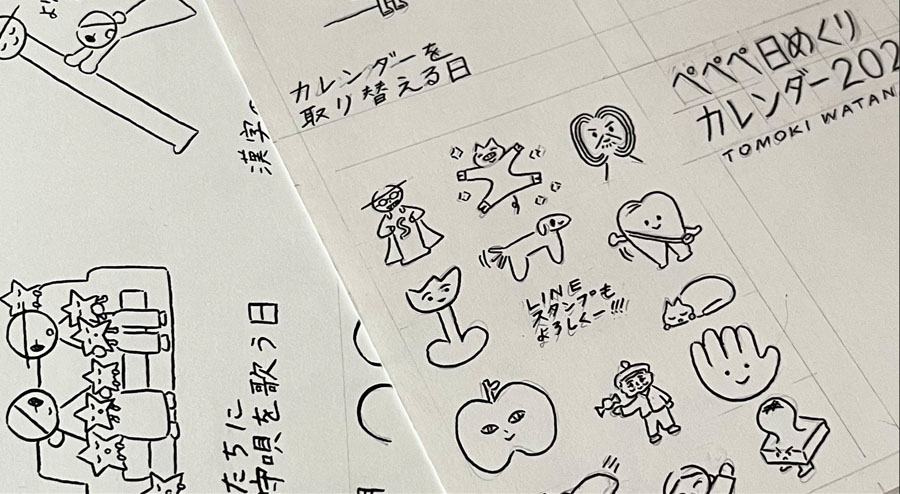

We move to the next room, separated by the common Japanese sliding doors, to see the original drawings of the Pepepe 2023 calendar31.

D. “Is this your studio? Do you work here?”

T. “Yes, although it’s more of a garbage room ha ha,” he answers in English.

D. “It has a beautiful light; we love the artist's mess. These sliding panels, depending on whether they are open or closed, modulate and transform the space. I love this house, full of art and objects.”

T. “When you contacted us and we saw the Instagram of @coleccionesdeartistas, all the houses were beautiful….”

N. “We told ourselves, ‘And now what do we do’?” —they joke.

D. “This house is beautiful, full of details.”

On a table lies the recently finished sheets, divided into grids, with several calendar days on each one. They are handmade drawings, which will soon go to print and will go on sale at the end of the year, as has been the case since 2014.

D. “Tell me a little about how you do it. Is there a theme or story for each year? Are they different stories?”

T. “There is no story. For me, the text or message comes first, then the drawings.”

While Marisa translates some of them for me, she explains that every day is a different story. There is no continuity.

D. “How do you get inspired to write each day?”

T. “During the day I have some ideas. If I have a deadline and I still have some left to finish, I start doing more things and going out, go to a coffee shop, for example. Sometimes in half an hour a single idea occurs to me, and sometimes the idea comes out of nowhere and I write it down on my cell phone.”

D. “The stories have a lot of humor, don’t they?”

T. “Yes. I make it this size because I find it convenient.”

D. “I love small things, and I see that you do too.”

T. “Yes, yes. I’ll send you one later.”

D. “And where is that portrait photo from?” I say, pointing to a portrait of Tomoki that hangs on the door lintel.

T. “It is a traditional costume from Thailand. Something that tourists use when they go there.”

D. “Like when tourists visit Japan and dress up in kimono.”

T. “Sure.”

D. “Tai kimono.”

A. “The expression you have in the photo is interesting, it is perfect for that suit.”

Behind Tomoki hangs another type of calendar, one of a traditional shape and size.

T. “It’s a calendar that we do at the school I’ve been working for since 2015, with young people who have some type of disability. Every year they make this calendar with some drawings.”

D. “Oh yes, I read something about that.”

It reminds me a little bit of another story from the Artists’ Collections book, and I show him the pages of the artist Mariela Scafati32.

D. “She taught for many years in an institution for patients with different pathologies, mental illnesses, the Blanquerna Institute. And when the institute closed, she saved some drawings of these students. She also told me in the interview that the painting of one of the students helped her to think about her own work. She tried to imitate painting, to understand how someone can paint in that way.”

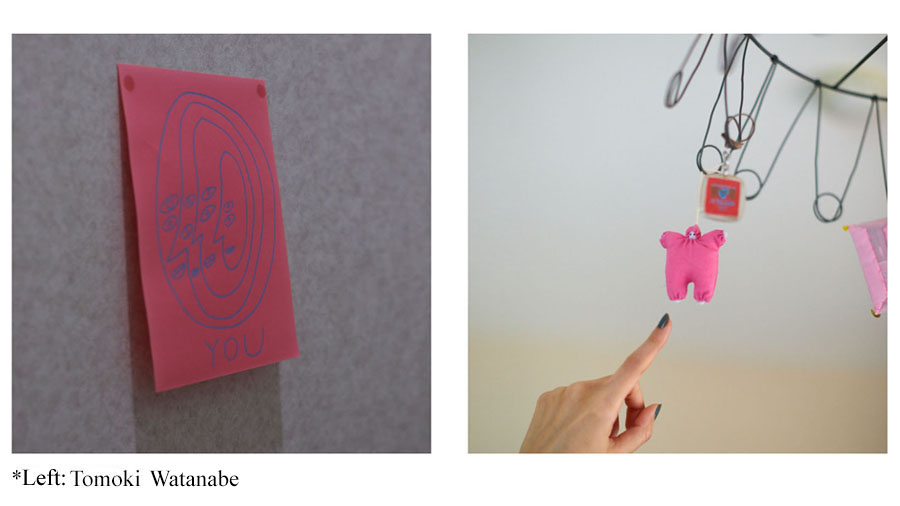

T. “It’s a beautiful painting. We are two teachers, Ritsuko Ozeki (1971 -)33 and I,” he tells me while we look at the calendar drawings, and then we head to the bathroom to see another piece. “This drawing is from the other teacher, a pretty famous artist, who exhibits in the United States every year. Then there is this drawing in pink that is mine. This is a building that is prepared for older people, and here is a button for emergencies. I put this work here to cover that button.”

D. “I’d like to know something about the recent exhibition you did at Edane, in Osaka, early this year, called Come on to my house.”

T. “There were mainly works on fabric, by Pe34. It’s my project, but Nat-chan helps me with the embroidery, we do it here at home.”

D. “Pe,” I repeat, trying to imitate Tomoki’s pronunciation. “I saw another exhibition that I liked, I kept calling your name, at Bagel and Café Gallery, in the city of Tottori. I wonder: what name?”

He laughs and says softly, whispering: “Nat-chan.”

D. “Is it the same story from the book we saw earlier?”

T. “Well, the main concept of all my work is: love yourself, be good to others; it’s a way to contribute to society, I think. So, the answer is Nat-chan. There’s a text that goes with this title as well,” he answers while looking up a text on the blog, and they translate it for me:

“You / walking / on the opposite bank

I / just wanted to tell

The fun times / memories of the two of us

I still cherish it / that it’s here”.

D. “It’s like a poem.”

T. “Yes.”

D. “I love the coverage you do of this exhibition on the blog. The photos with the people and art works, all that community that moves around them. It’s nice to see what happens with that.”

In a blog post he wrote: “Whether you use it or decorate it, it’s a luxury to be able to interfere with many people’s daily lives! This makes me happy.”

D. “Tell me about the Mori Michi35 fair in Aichi, in which you recently participated. I read that you worked eight hours a day making portraits and that people lined up waiting to get theirs.”

N. “It is a fairly large event, with various stages, food stands, shops and craft stands, books, art, live music. Stands are set up with people who come from all over the country.”

T. “Most are food stands, then there are a lot of crafts. There was also a section from Taiwan at the event.”

D. “How does it work? Do you charge for the portraits?”

T. “Yes, each one poses for five minutes, and it costs 1,000 yen (8 dollars). I don’t talk to them, I’m very serious when I make the drawings, Japanese people are very shy. If someone wants to chat, I get serious, because there are people waiting. When I have time, I talk to them more, but there it was not possible. The shop is very popular, they wait for an hour sometimes. So, I try not to talk to them too much.”

D. “How many did you do?”

T. “One hundred a day, for two or three days.”

D. “How was your hand after that?”

T. “Broken,” he answers in English, “and not only my hand.”

D. “What did you do with the money?”

T. “I paid the rent ha ha.”

D. “And buy art. Before I go, I have to ask you this question: why do you always wear pink?”

T. “I don’t think about it much. I wear the same thing almost every day; for example, I wear these pants about 330 of the 365 days of the year.”

D. “Is it like your uniform?”

T. “It’s that I just have this, I didn’t think about it.”

D. “I’m not buying it.”

T. “Speaking of pink, when I go to buy chewing gum, for example, there are blue, green, and pink ones, and maybe I want another color, but I always end up choosing pink. I unconsciously like pink. The same thing happens to me with food, I choose things that have pink. In high school I wore a boring beige momohiki all day, like old people. From a distance I looked naked. My school motto was “Freedom,” you could dye your hair, wear piercings. Something unusual in Japan, because we didn’t wear a uniform.”

D. “Here the uniforms seem from another century, with those big collars and hats. Mami Goda, our mutual friend, told me that when she first met you, you used to wear a sweatshirt as pants.”

T. “Oh yes, ha ha! It’s true, I used it with suspenders.”

D. “It seems to me that you care how you dress, you have a sense of fashion that is important to you. That is why I chose this work by Ana Clara Soler36 as a gift, because the main character is a pink man.”

T. “It’s beautiful, it surprises me, thank you! Now I am more relaxed. In high school I had the intention of doing something that nobody else did. Five years ago, I had a leopard phase, for example. Today I dressed especially for you.”

D. “I was wishing for you to do it, thank you.”

T. “You’re welcome.”

We stand up, ready to say goodbye, when Tomoki’s mom appears from the end of the hall. We’ve been there for more than two hours, going through every corner, and we never saw her. They make a joke like “we had her locked up” while we chat around the table. It surprised me that older people feel very comfortable chatting with me, even though we clearly don’t speak the same language, and instead young people cover their mouths as a sign of shyness before saying something in English.

Trying not to make them feel uncomfortable, I ask the translator how they usually greet each other in Japan, if it’s better to shake hands, or a hug (I realize kissing is not an option). He tells me that with the “corona” it is better not to touch each other too much. Tomoki approaches and holds out his hand, and then gives me a hug with an “It’s okay” gesture. Once in the hallway, on my way to the door, I dare to make a joke and say: “Now your mom can use the bathroom,” and we laugh.

Interview: Daniela Varone

Photographs: Marisa Shimamoto

FOOTNOTES

1 Tomoki´s website: https://suetomii.wixsite.com/tomoki and his blog: https://ameblo.jp/suetomi1980/entry-10428550119.html?frm=theme

2 Tenugui: rectangle of printed cloth. Its origins date back to the Heian era, 794 to 1192 AD. With unlimited uses, the tenugui became a necessity. Like modern kendokas, samurai wore them under their helmets to protect their foreheads from sweat and, thanks to the lack of seams on the edges, they could also be easily torn if they wanted to use them as a bandage. This seamless edge feature allows for easy wringing and quick drying, hence its use in onsen baths. As the tenugui grew in popularity, it entered the commercial scene and became a promotional product. Businesses, kabuki performers, and sumo athletes sell or give away tenugui adorned with their names, images, or logos. Families acquire tenugui with their kamon or family crests.

3Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

4Koji Kumagai: https://panorama-index.jp/kumagai_yukiharu/

5Ko Soda: www.sodako.com

6Amigo Koike: http://en.tis-home.com/amigos-koike/

7Furuya Usamaru studied sculpture at art school and also became involved with Butoh dance. For a while he worked as a high school art teacher, where he met Tomoki. He made his debut as a manga artist with the groundbreaking Palepoli strip, which was serialized in the legendary avant-garde comics magazine Garo in 1994. Since then, he has published in Japan’s major weekly magazines.

8Astro Boy (published between 1952 and 1968 and adapted into a television series in 1963) is a manga series written and illustrated by Osamu Tezuka (www.tezukaosamu.net). According to the story, set in 2003, the powerful android was created by Doctor Tenma, head of the Ministry of Science, to replace his son Tobio (Atom in Japanese), who died in a car accident. Tenma incorporated Tobio’s memories into Astro and began to treat him as if he were his son. I’m going a bit off topic, but Japan has a long and close relationship with robots, ranging from mechanical karakuri ningyo puppets to Hiroshi Ishiguro’s current geminoids (his own and his five-year-old daughter’s). In line with the link between Doctor Tenma and Astro, the older models of Sony’s Aibo dog-robots, which can no longer be repaired, receive, like the living, funeral rituals at the Kofuku-ji Buddhist temple, accompanied by farewell letters from their caregivers. For animist Shinto, all things have their energy, or what we call soul. See: https://www.abc.es/tecnologia/abci-japon-celebra-entierros-budistas-para-perros-robot-201805031805_noticia.html

9Meriyasu Kataoka: @kataokameriyasu y ver: https://www.japantrends.com/stuffed-animals-designer-makeover-meriyasu-kataoka-fashion-show/

10 Maeriyasu Kataoka´s interview: https://tokion.jp/en/2022/02/03/a-stuffed-toy-artist-meriyasu-kataoka/

11 Kokeshi dolls originate from the cold Tōhoku region, an area of rice farmers and woodworkers. With the leftover wood, the locals began to make these dolls for the little ones. Tōhoku is also a mountainous area full of hot springs (onsen), and soon became a destination to visit and activated the economy of the place. Kokeshi dolls became a souvenir that visitors took home after visiting the hot springs. They are considered objects related to good fortune and the favor of the gods, and are currently produced in different areas of the country, and in some cases through different generations of artisans.

12Kuu Kuu Minami: www.kuu-kuu.com

13The chrysanthemum and the sword. Ruth Benedict, Anthropology Alianza Editorial, 2010. The book was originally published in 1946.

14Izumi Suzuki: https://kokeshka.theshop.jp/items/29431119

15 The Mingei movement arose in Japan in the 1920s, founded by the Japanese writer and philosopher Soetsu Yanagi (1889–1961) in collaboration with ceramists Shoji Hamada (1894-1978) and Kanjiro Kawai (1890-1966). It seeks to enhance the products created by groups of anonymous artisans, as a response to the industrialization of Japanese society due to Western influence and as a reflection on the role of Japanese artistic traditions in a modernizing world. It was inspired by the English Arts & Crafts movement. See: https://mingeikan.or.jp/?lang=en

16Japanese dolls. The fascinating world of ningyō. Alan Scott Pate.

17Karakuri ningyō: https://conoce-japon.com/cultura-2/karakuri-ningyo-los-automatas-japoneses/

18Museum Miraikan: https://www.miraikan.jst.go.jp/en/

19Hiroshi Ishiguro (1963 -) is director of the Intelligent Robotics Laboratory, part of the Department of Systems Innovation, Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University, Japan.

20Seal robot Paro: https://youtu.be/oJq5PQZHU-I

21Japan from a capsule. Robotics, virtuality and sexuality. Julián Varsavsky. Adriana Hidalgo editora, 2019.

22Saeko Takahashi: http://www.saekotakahashi.com/ @bacchiworks_saeko

23Kazuhiro Tanaka: https://www.artsper.com/hk/contemporary-artists/japan/5415/kazuhiko-tanaka

24Laura Ojeda Bär: https://cargocollective.com/laura-o

25Ryoji Arai: www.ryoji-arai.com

26Mamiko Nakamura: @banryoku_mamiko.n

27Wan: @wanwanwonderland

28Takehide Harada: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2017/05/04/films/approaches-50-iwanami-hall-remains-vital-cinema-lovers/

29Iwanami Hall: https://jff.jpf.go.jp/read/news/iwanami-hall/

30Hiroko Watanabe: @hirocoro43 / http://hiroko-watanabe.com/

31In this blog post we can see the production process of Tomoki’s calendar in the city of Kanazawa: https://ameblo.jp/suetomi1980/entry-12771292427.html

32Mariela Scafati: @scafatiscafati

33Ritsuko Ozeki: @littleko316 and also see: https://www.ritsukoozeki.com/

34@pe_isgood. In the account description it says: Hand embroidery works of illustration by Tomoki Watanabe.

35 Mori Michi Fair: www.morimichiichiba.jp

36 Ana Clara Soler www.anaclarasoler.com.ar