FOOTNOTES

1Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

2Yuna Ogino: https://www.yuna-ogino.com and @yuna_ogino_

3Jun Yonekawa: @mondunique

4January: it is tradition to place a pine tree on each side of the front door of houses during the New Year’s Eve. Pine leaves are perennial, resistant to heat and cold, and remain green during all four seasons. As it is also very long-lived, the meaning of “immutable prosperity forever” is attributed to it. For this reason, the pine tree is chosen for the month of January.

5The tokonoma is an essential space of a tatami room, a separate area in one corner of the room, set aside as a miniature art space. With the subtle changes of the seasons, the decorations of the tokonoma also change. Hanging scrolls display a painting or a famous calligrapher's rendition of a traditional, seasonally appropriate poem. An ikebana arrangement captures in miniature a landscape with flowers and plants of that season, often the same landscape, which is the subject of the painting or poem on the hanging scroll. Other decorations may include a treasured antique or a framed painting that rests on the floor of the tokonoma.

6Sakura blossom: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/03/23/national/cherry-blossom-forecasting/

7Julían Varsavsky, Japón desde una cápsula. Adriana Hidalgo editora, 2019.

8Masayuki Oku: https://www.okuart.com/

9Hidemi Takaku: https://suiran8art.base.ec/

10Arisa Odawara: @arisaodawara

11Yoshitomo Nara: https://www.yoshitomonara.org/en/

12 Yoshitomo Nara prices at auctions: https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-yoshitomo-nara/record-prices/yoshitomo-nara-record-prices

13N´s Yard: https://www.nsyard.com/en/about/

14N´s Yard Garden: The garden retains the area's native trees alongside seasonal plants. In spring, visitors can enjoy various flowering plants, including three varieties of sakura. Summer brings wonderful greenery, along with flowers such as the Japanese spiraea and Hydrangea involucrate. Golden-rayed lilies grow wild around July - August, while September - October brings the flowers and scent of the fragrant olive. From autumn to winter, visitors can view the red and yellow leaves of several Japanese maple varieties”. https://www.nsyard.com/en/about/yard/

15Jenny Saville: https://gagosian.com/artists/jenny-saville/

16Sumiko Iwaoka: on her www.sumikoiwaoka.com she wrote: “In my recent works, my interest has turned to the world that becomes visible when you superimpose the universal beauty of masterpieces with the daily life that passes by.”

17Book: Ukiyo, Yoshitomo Nara. Publicado por Masaku Takei (Little More), 1999.

18Chu Asai: https://www.artizon.museum/en/collection/category/detail/252

1921_21 Design Sight is a museum dedicated to design, founded in 2007 by architect Tadao Ando (1941–) and designer Issey Miyake (1938–2022) It is located in an area called Tokyo Midtown, that was created to be the center of design culture in Japan, driven by facilities including 21_21 Design Sight, Suntory Museum of Art, and Tokyo Midtown Design Hub. Tokyo Midtown is home to the National Art Center, Tokyo, the Mori Art Museum, the design-themed complex AXIS, TOTO GALLERY•MA, and a number of design offices.www.2121designsight.jp.

20Nihonga paintings are done on washi (Japanese paper) or silk. Initially they were produced to hang on rolls that were moved by hand or on screens. In the case of monochrome paintings, sumi (Chinese ink) is used, based on soot mixed with a fishbone glue. In polychrome paintings, the pigments are obtained from natural ingredients: minerals, shells, corals, and some semi-precious stones (malachite, azurite, and cinnabar). For these powdered pigments, a hide glue solution, called nikawa, is used as a binding agent.

21Chihiro Ogawa: www.ogawachihiro.com

22Sato Sugamoto: www.sato-sugamoto.com

23Asuka Takamatsu: http://takamatsu-works.blogspot.com/

24Shika: www.shikartworks.com

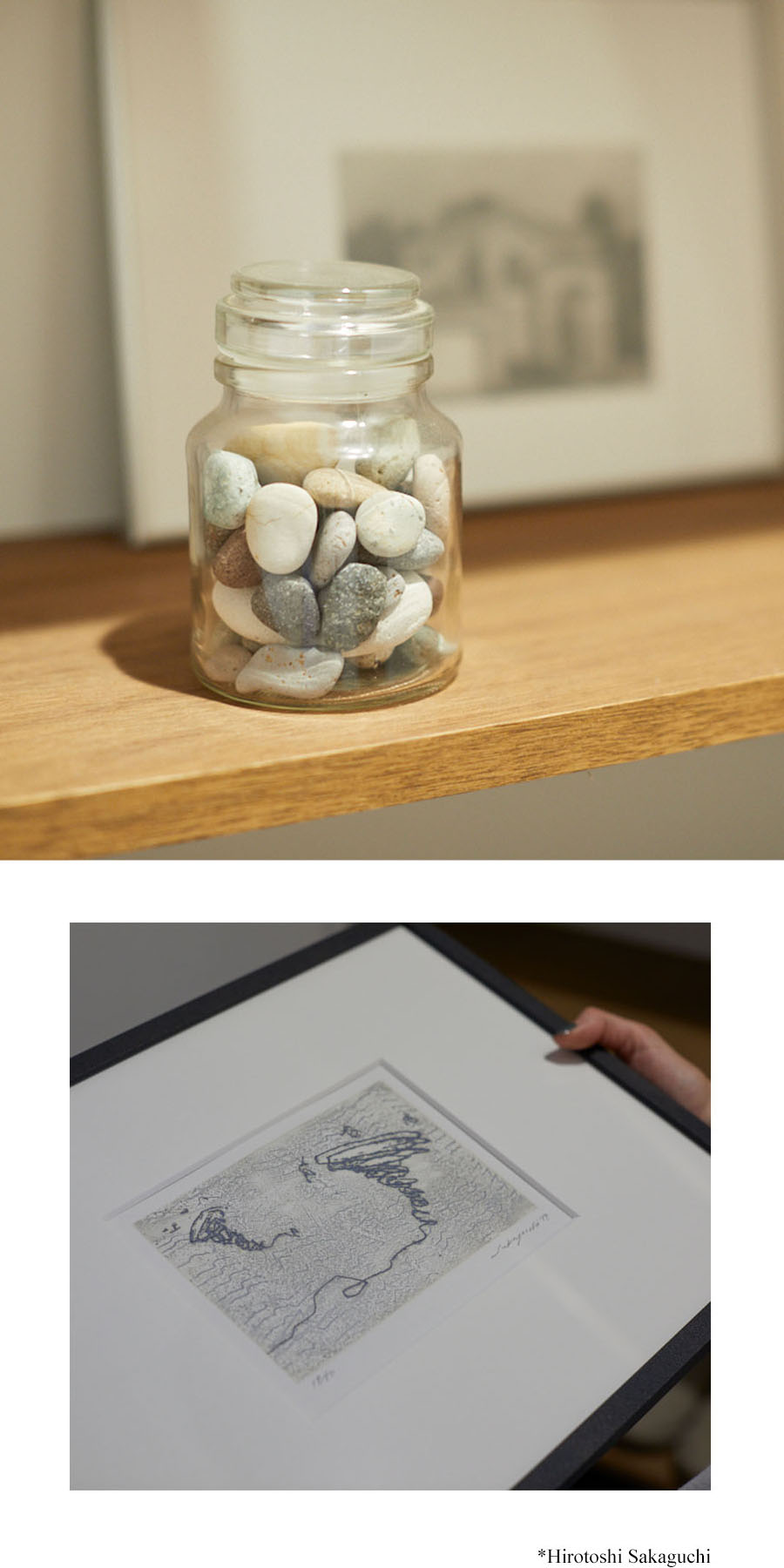

25Hirotoshi Sakaguchi: https://www.gallery-58.com/exhibition/2022_exhibitions/2022_sakaguchi/

26Ayaka Terajima: https://ayakaterajima.myportfolio.com/work

27Roppongi Art Night: https://www.roppongiartnight.com/2022/en/

28Takashi Murakami: https://gagosian.com/artists/takashi-murakami/

29Tokyo University of the Arts: https://www.geidai.ac.jp/english/

30 Yōga and Nihonga Paintings: In 1876, the Meiji government created the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko (Technical School of Fine Arts), Japan's first art school dedicated to Yōga—the style of painting by Japanese artists done in accordance with Western (European) conventions, techniques, and materials. To carry out this mission, they hired some Italian artists as teachers, among them Antonio Fontanesi (1818-1882). However this school lasted less than a decade.

In the 1880s, the general reaction against Westernization and the growth of the Nihonga movement (Kakuzō Okakura (1862-1913) and Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908) are two standard-bearers in this cause) caused the temporary fall of Yōga. The school had to close its doors in 1883, and when the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko (precursor of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music or Geidai) was created in 1887, the Western painting department no longer figured on its curriculum. The following year, Kakuzō Okakura was appointed director. Okakura was a member of the Imperial Art Commission sent by the government to investigate art in Europe and the United States, but instead of being fascinated by foreign productions, he had an intense appreciation for Asian and Japanese art.

But the encounter was not going to end there, and in 1889 Yōga artists created the Bijutsukai Meiji (Meiji Fine Arts Society) and in 1893, the return of the painter and teacher Seiki Kuroda (1866-1924), considered the father of Yōga, from his studies in Europe gave a new impetus to the genre.

When it became clear that European methods were to become increasingly important in the school's curriculum, Okakura resigned his position and in return founded the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Academy of Visual Arts), along with 39 other artists, where they spread their aesthetic nationalism.

Since 1896, a Yōga department is part of the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko study department, Seiki Kuroda was invited to be its director, and henceforth Yōga became an accepted part of Japanese painting.

31Sōfū Teshigahara: https://www.takaishiigallery.com/en/archives/26602/

32 Sōgetsu: https://www.sogetsu.or.jp/e/works/

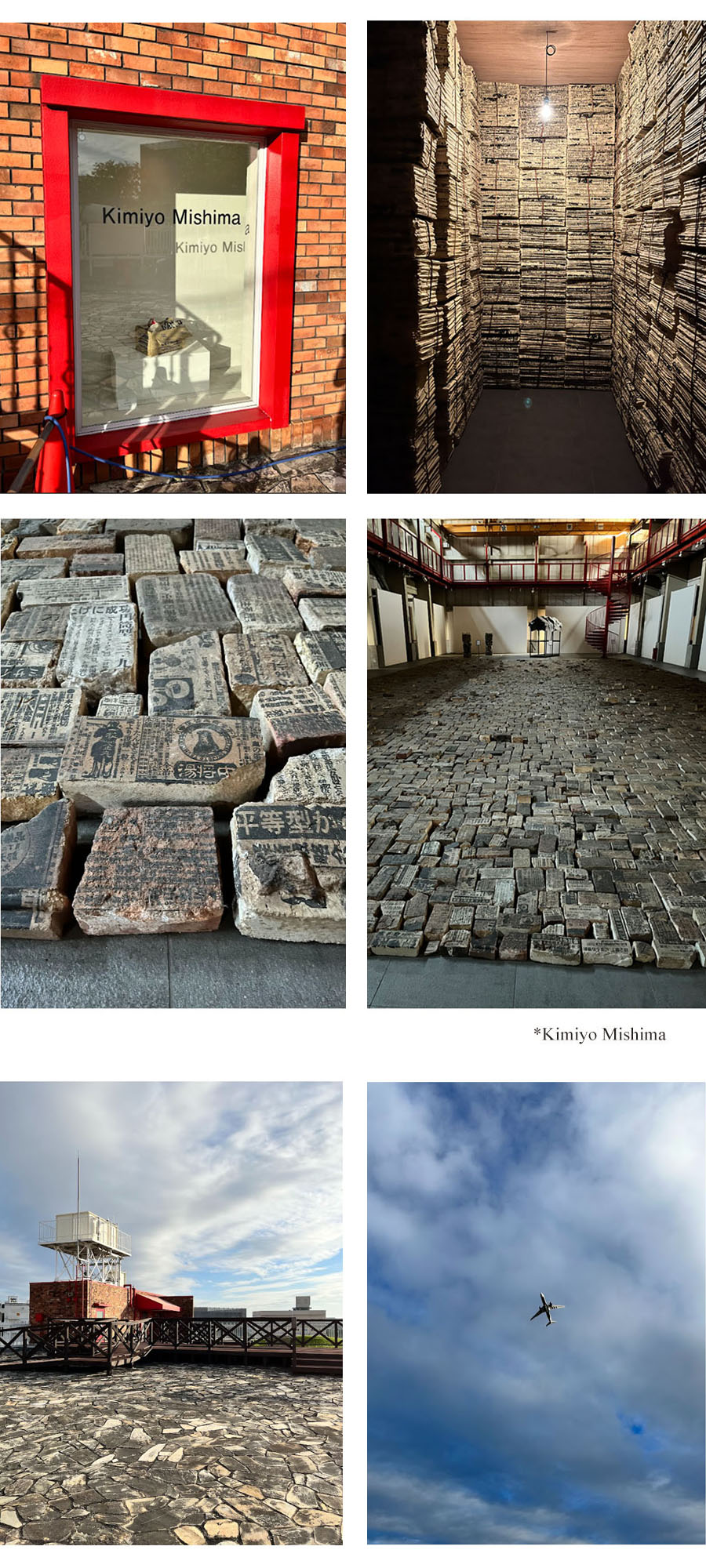

33Camille Henrot: https://mennour.com/exhibitions/is-it-possible-to-be-a-revolutionary-and-like-flowers

34Yukio Nakagawa: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-585-2003-01-19.html

35Mizuma Art Gallery: https://mizuma-art.co.jp/en/

36Art Factory Jonanjima: https://www.artfactory-j.com/

37Kimiyo Mishima: https://mem-inc.jp/artists_e/mishima_e/and a video of the show: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIVOFgP4vCg

38Manami Hayasaki: www.manamihayasaki.com

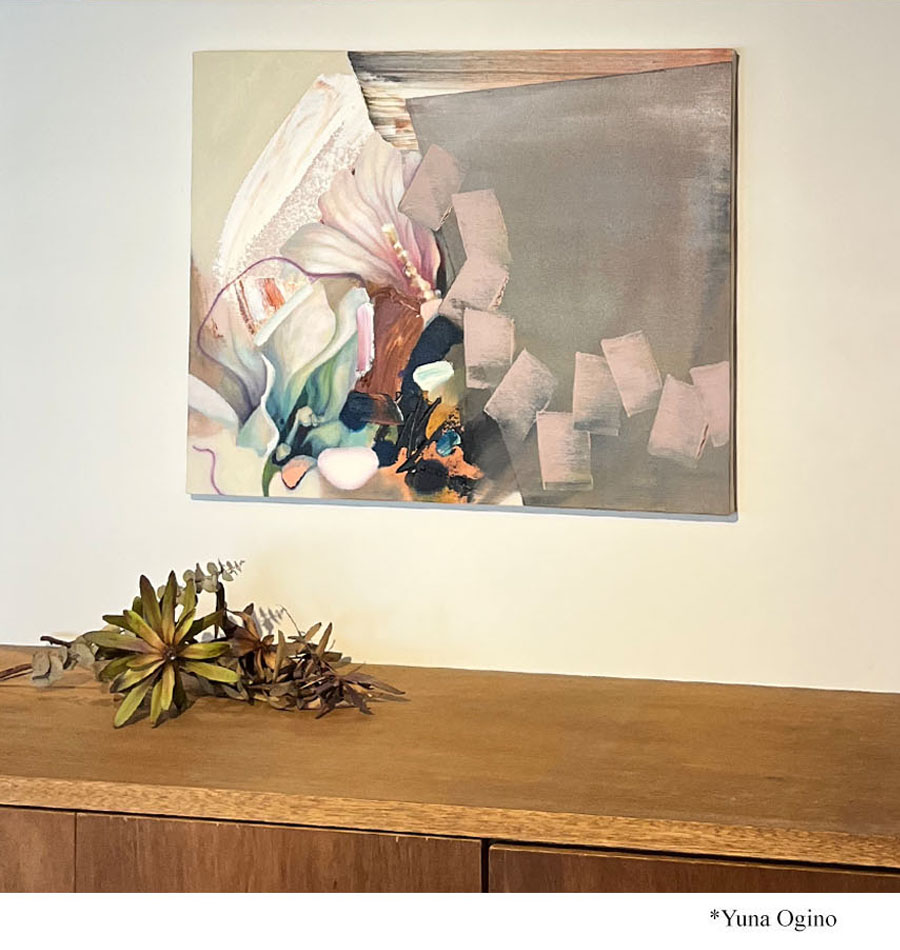

“I enjoy having some works nearby”

Yuna Ogino

“The streets of this city have no names,” writes Roland Barthes in Empire of Signs. Although there is a written address, he adds, it has only a postal value, it refers to a plan, which is clearer for the postman than for the common visitor. The streets of Tokyo do not have numbers either, and although Google Maps solves the mystery, it is Marisa Shimamoto1, photographer of this project, who leads us to the doors of the interviewees.

She picks me up at the AOI cafe a few minutes before 1:00 p.m. and we go together in her car to Yuna Ogino’s (1982)2 house. The issue of parking in this city deserves a separate chapter; I will only say that we left the vehicle in the parking lot of a nearby supermarket and that we were not the only ones.

Yuna lives with her daughter Mii in the Ōta neighborhood, an area located thirty minutes from the mega busy Shibuya station and quite close to Haneda International Airport. A few months ago, she completely redesigned the apartment together with the architect Jun Yonekawa3. The kitchen, the living room and the bedroom now form a single space. To do this, some walls were demolished and the traditional tatami that covered the floor was removed. The room was visually uniformed with two simple resources: few materials and the use of brown color.

Although distant, it still retains some reminiscences of traditional Japanese architecture both in the choice of wood and in the management of light. This enters the space filtered no longer through rice paper (as in the Shōji doors), but by white curtains and frosted glass. It’s still a stripped-down space, but now it’s very contemporary; even the air extractor and some pipes are visible.

D. “How long have you lived in this neighborhood?”

Y. “I have grown up here. My family lives in the area and my daughter’s school is close as well.”

D. “The first time I came to Japan, I was surprised to see the children go alone down the street. Does your daughter go to school by herself?”

Y. “Yes, it’s super safe, she goes and walks back alone. She’s been doing it since she was in first grade.”

Yuna speaks to me in Japanese, but she understands many of the questions I ask her in English and sometimes she feels at ease answering me in that language. She is super kind and has a laid-back attitude. The interview audios are full of silences, which are sometimes filled only with our laughter.

In addition to the Artists’ Collections book, I bring with me as a gift a candle that I bought at the IDLB store in Buenos Aires.

D. “I saw a photo of your house on Instagram and I thought you were going to like it.”

Y. “Yes! I love it,” she says with surprise. “I just don’t think I can light it in here, ha ha.”

D. “Don’t use it, it’s a decorative object.”

M. “Only light it if you have an emergency, ha ha,” adds Marisa, who has the double task of taking the photographic record and helping us with the translation.

In a section of the house near the entrance I recognize the first work…

D. “This painting is yours, isn’t it?”

Y. “Yes, they are birthday flowers,” she answers in the shy English that most Japanese speak.

M. “Do you have something like this in Argentina?” Marisa asks, seeing the intrigued expression on my face.

D. “No, I don’t think so.”

M. “For example, a certain plant corresponds to January4another to February… and so on.”

Y. “This one on the left is my daughter’s flower and this one is mine. I was born in September and my flower is the rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus). My daughter was born in July, so her flower is the lisianthus. You will find many versions depending on the month, but I chose the flowers that I wanted to paint.”

D. “Oh, I see, it’s the two of you. And by the painting you put this flower arrangement. Is it a kind of ikebana?”—I am the one who timidly ventures to speak now.

Y. “Yes,” she answers, and laughs.

In the contemporary Japanese home, the tokonoma5, which once housed a painting or calligraphy and a flower arrangement, no longer exists, but this space certainly keeps something of that spirit. Since ancient times, the Japanese have attached great importance to nature and the changes of the seasons.

The worldwide famous cherry blossom—or sakura6 —season is perhaps the most important cultural and economic event of the year and signals the beginning of spring. Japan is the only place in the world where the media broadcast the progress of flowering on a daily basis, following its evolution across the archipelago to the north. Some meteorological agencies take references from 1,000 locations in different cities of the country.

Just a few days after the long-awaited moment of hanami (flower viewing) and picnic in the parks, the petal shower called hana fubuki (flower snowfall) arrives and the parks explode with people again. “Starting with a flower, the Japanese go from romantic exaltation to deep melancholy in a week,” writes Julián Varsavsky7 adding: “It is not when it opens that the flower reaches its maximum beauty—as it would be seen in the West—, but when it withers.”

Y. “I made this painting with flowers specifically for this sector of the house,” she tells us while her hand runs along the frame of the sliding door that looks like the edge of a canvas stretcher, but made of wood. Sliding the door, she shows us that the drawing of its veins accompanies the general design of the furniture.

There are very few objects and some plants in the room. An air plant that hangs over the kitchen catches our attention, and then Yuna gives in to demonstration and waters it with a spray.

D. “Is the architect your friend?”

Y. “Yes, he lives between the cities of Tokyo and Paris. He designed some famous pastry shops in France, with French style.”

In a corner of the kitchen we see the second work: a cassette box that contains a small painting.

Y. “My collection.”

D. “Whose work is this?”

Y. “Masayuki Oku (1992)8,” she responds, checking the name that appears inside the box.

D. “Did you buy it?”

Y. “Yes, I paid 10,000 yen (75 dollars) for it.”

D. “How did you meet him?”

Y. “I went to an exhibition in a gallery where my assistant was showing, and he was also exhibiting in the room.”

D. “Do you work with a painting assistant?”

Y. “Yes, she helps me prepare the canvases, the backgrounds. I actually have one of her works,” she says, pointing to another corner of the kitchen. Her name is Hidemi Takaku9.

D. “You will have to help me and write down all those names for me later.”

Y. “Look, this is her Instagram.”

D. “How long has she been your assistant?”

Y. “We worked together for three years.”

D. “Was she a student of yours? Or how did you meet?”

D. “Did you buy this work or was it a gift?”

Y. “I bought it, it was very cheap, about 3,000 yen (22 dollars).”

D. “Do you have more works in the kitchen sector?”

Y. “I think not.”

While Marisa is busy with her double job, I look around for more works. The first thing I see in the bathroom door is a small rhomboid window with a flower that Yuna made using the vitraux technique. Every corner of the house seems designed as if it were a painting. Putting together a composition, which I doubt is casual, the perimeter of the living room is full of small paintings on paper that draw a vegetable frieze on the floor. Flowers, spots, many colors contrast with the dark color of the wood.

D. “Is this normally like this or did you place them there for us?”

Y. “I have more in general.”

D. “So, you like to watch them”.

Y. “These are works in progress.”

D. “Ah, that’s right, they still have the masking tape around the edges. Are they sorted by color, or it seems to me? They range from browns, to pinks, to violets…”

Y. “I didn’t plan it like that,” she says, and laughs, “but I guess it’s unconscious.”

D. “I love the floor, I never saw anything like it in Japan.”

Y. “Thanks. It’s a parquet called French herringbone, because of its pattern.”

M. “Yes, it is very rare here.”

D. “There is a storage place on the floor, a secret compartment. What do you keep there?”

Y. “Nothing, it came with the house, before there was a tatami on the floor. And traditional houses had these storage spaces to put the cushions under the tatami.

Less than two meters away, she shows us another secret space in the living room. Behind a wooden blind that blends in with the rest of the walls, is her built-in bed in a custom-made niche.

D. “Do you also paint at this table?”

Y. “Yes, sometimes I use this space to work.”

D. “Does your daughter paint with you? She’s 9 years old, right? What’s her name?”

Y. “She is 10 years old; her name is Mii. At the moment she has no interest in painting, she prefers to study.”

Leaning on the floor, against the balcony window, there are some more works that were waiting for us when we arrived at the apartment.

D. “Tell me a little about these works that you prepared here. This drawing with two women.”

Y. "It’s a work by a friend, her name is Arisa Odawara10. In fact, this is the first work I had. I paid 10,000 yen (75 dollars) for it. I bought it in a small gallery that was in another neighborhood, where I lived before.”

D. “When does your collection start more or less?”

Y. “Oh, I was in my twenties…”

D. “Twenty years ago then… more or less. I’m 41 now,” I tell them, referring to the fact that the three of us are the same age.

M. “I’m 42.”

Y. “Just yesterday was my birthday, I turned 40.”

D. “Yesterday?! Oh, what a surprise. Happy birthday! Did you have a good time?”

Y. “Yes,” she answers with a smile.

D. “Do you like living with the works of other artists?”

Y. “The truth is that I am not very aware of that. I think I pay more attention to my own works inside my house. Now that I’m at a point where I’m satisfied with my own work, I enjoy having some works nearby.”

D. “If you could buy the work of any artist, who would you buy from?”

Yuna gets excited about the imaginary question and starts making mental lists with a big smile.

Y. “Yoshitomo Nara (1959-)11," she answers almost immediately. I think Nara needs no introduction. He is also famous for the millionaire prices that his paintings reach in the main auctions around the world.12

D. “We can't even dream of having a lithograph. However, from what I saw these days, we could settle for some offset printing, (numbered copies) that can be purchased for more friendly prices.”

At the end of 2017, the artist opened N's YARD13, a private space dedicated to his work and contemporary art, in Aoki, Tochigi Prefecture. Located in a natural environment, it includes a large garden with a wide variety of native trees and flowers14 as detailed on the website. This initiative “was born from Yoshitomo Nara's desire to establish a place in Japan where his works could be enjoyed in a more informal and personal environment (...) In addition to a diverse selection of Nara's works, paintings, drawings and three-dimensional works, the five showrooms contain exhibits personally curated by Nara, including his collection of records, dolls, and pieces by other artists”.

It’s intriguing that one of the most expensive (and reproduced) artists on the contemporary scene decides to create his own space with a store dedicated to selling posters, signed by N's Yard, at affordable prices and within everyone's reach ($14). Then, there are also some offset print copies like “Sorry, couldn’t draw the left eye!” (2003), 50 x 70 cm, available for 50 000 yen (390 dollars) in a small gallery in the Ginza neighborhood, and the complete series of eleven prints with the N's Yard stamp even appears in some well-known auction houses for a base of 800 dollars.

Y. “It seems expensive to me anyway. I also really like the paintings of the British artist Jenny Saville (1970–)15 though I don’t know if I’d live with a work of hers; but I respect her a lot as an artist.”

D. “Do you have artist friends who also collect art? Is it a common practice?”

Y. “A few I would say, it doesn’t seem so usual to me.”

D. “Do you consider that you have an art collection?”

Y. “Yes; I doubt a little, but I have some works that I am sure are part of my collection and I would like to have more pieces of this type, like the one by the artist Sumiko Iwaoka (1982)16, for example.”

D. “In general, the collections of artists are rather organic, they speak of the art community, of the personal stories of each one, of affections. There is no logical program, no script, no plan. I love this work by Sumiko, it must be the most important piece in your collection too. Did you buy it?”

Y. “Yes, I bought it”.

D. “Did she buy a work from you too?”

Y. “No, or not yet at least,” she answers, laughing.

D. “How did you meet?”

Y. “In college, but we met after graduation, through a friend. In this work, on one side she cuts out a sheet of a painting by a famous Japanese artist and, on the other side, she repositions the figure in an oil-painted landscape. The paths that run through both scenes are similar.”

D. “This work by Sumiko makes me think a bit of Nara too. Recently, our mutual friend Mami Goda showed a book from his series “In the Floating World”17, in which Nara works on the images of the famous Ukiyo-e (block prints from the Edo Period) making them part of his work. For example, the red Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is transformed by Nara into a snowy mountain from which one of his characters skis down, while a snowman awaits her at the base. In her talk, Mami related it to the concept of "borrowed landscape", taken from Japanese architecture. She recounted that, in traditional houses the exterior landscape is used as one more resource, it is ‘borrowed’ and incorporated into the interior through the windows. Somehow, I associate this with what Sumiko does, but, on the contrary, what she ‘borrows’ from the history of art is the human (or animal) figure and she repositions it in a new scene of daily life, from another time."

Y. “Ahh, yes, I understand.”

D. “Do you know if she always uses Japanese paints as a base to cut out the figures?”

Y. “Not always, in fact, many of them are from Western artists.”

D. “What is the name of the Japanese artist who painted the left side of the work?”

Y. “Chū Asai (1856-1907)18. Sumiko’s work is called The two people from Chū Asai’s “Landscape of Grez-sur-Loing” are now visiting the exhibition at 21_21 Design Sight19in Roppongi.

The Japanese painter visited France for the first time when he was 44 years old, and he was fascinated by Grez-sur-Loing, a historic town on the Loing River, near Paris, where an artists’ colony existed. Chū Asai studied at the Technical School of Fine Arts Kobu Bijutsu Gakko), the first art school founded by the Meiji government. There he trained with the Italian artist Antonio Fontanesi (1818–1882) during his brief stay in Japan, receiving a thorough education in Western art.

This is an interesting moment in Japanese art history: East meets West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chū Asai pioneered the art movement called Yōga (“Western style of painting”). The term Yōga was coined in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) and refers to the style of paintings by Japanese artists made in accordance with Western conventions, techniques, and materials; it is used to distinguish these paintings from traditional Japanese or Nihonga20paintings. This style meant the modernization of Japanese painting and the entry into the country of European pictorial techniques.

D. “Your friend Sumiko is also working with different historical moments; she takes the characters from the past and repositions them in the present.”

Y. “I’m not sure if they are necessarily from the past, but both images are very recognizable to the viewer.”

D. “For example, I saw a work where the ‘borrowed figure’ appears in a Uniqlo store, or buying toilet paper in the supermarket, with a lot of humor.” (The man from “The Four Elements: Air”, by Joachim Beuckelaer, is going shopping at UNIQLO, 2020; The woman from “Farm Girl”, by Alfred Roll, is purchasing rolls of toilet paper at the supermarket, 2020).

Y. “Of course, yes. I remember another one in which the character is waiting for the train at a station.”

Arranged on the floor, leaning against the window, there are some more works.

D. “Tell me a little about this other painting, is it a belly?”

Y. “It was a gift from my friend Chihiro Ogawa21it’s a drawing of my daughter’s tummy when she was three years old more or less. We were college friends too.”

D. “And this incredible bow?” I ask as I hold up a box with a gorgeous craft item inside.

Y. “It’s for the hair, it’s used at the Shichi-go-san.

M. “It is a tradition in Japan, a celebration for children, when they are three, five and seven years old. Shichi-go-san literally means that: three, five, seven. Three and seven are for girls and five for boys. The temple is visited, the girls wear kimono, it is to celebrate their growth and to ask for their health.”

D. “Is it something religious?”

M. “I’m sure that originally it must have been something more religious, but now it’s more like a ritual, or like a birthday. Some actually just take photos, but don’t go to the temple.”

D. “Was Mii’s in a Shinto or Buddhist temple?”

Y. “Shinto. When my daughter was three years old, I commissioned it from an artist friend who usually works with these materials, with ropes, ribbons. The artist’s name is Sato Sugamoto22 she tells us while looking for her on her cell phone to show us her work.

D. “Does she normally do this kind of thing on request, or did she do it because you asked her to?”

Y. “Well, she used to work for Tokyo Disneyland making costumes for Minnie Mouse and Mickey Mouse and she also took commissioned jobs.”

D. “I can’t stop thinking about this celebration that I don’t know anything about. Do people normally rent a kimono or buy it?”

M. “Well, there is everything, some rent, others buy, and some have a family kimono, the one they wore when they were kids, or an inherited one.”

D. “What did you do, Yuna?”

Y. “I rented it,” she answers, and laughs. “I have a photo album, I will bring it now.”

When she opens the album and we see a three-year-old mini Mii wearing a mini kimono with a mini bag, we die of cuteness. Kawaii!

D. “Oh, I imagined that the bow was located at the back, like in a tail, not in the front. In Japan everything works the other way around than I imagine, always. And do the children like it, do they have fun?”

Y. “The first half maybe yes, then they already want to go home, ha ha.”

We stayed for a while looking at the photo album and making all kinds of exclamations of surprise and tenderness. I asked a few more questions about this ceremony because it fascinates me, but I don’t want to bore you.

D. “Thank you for showing us the album.”

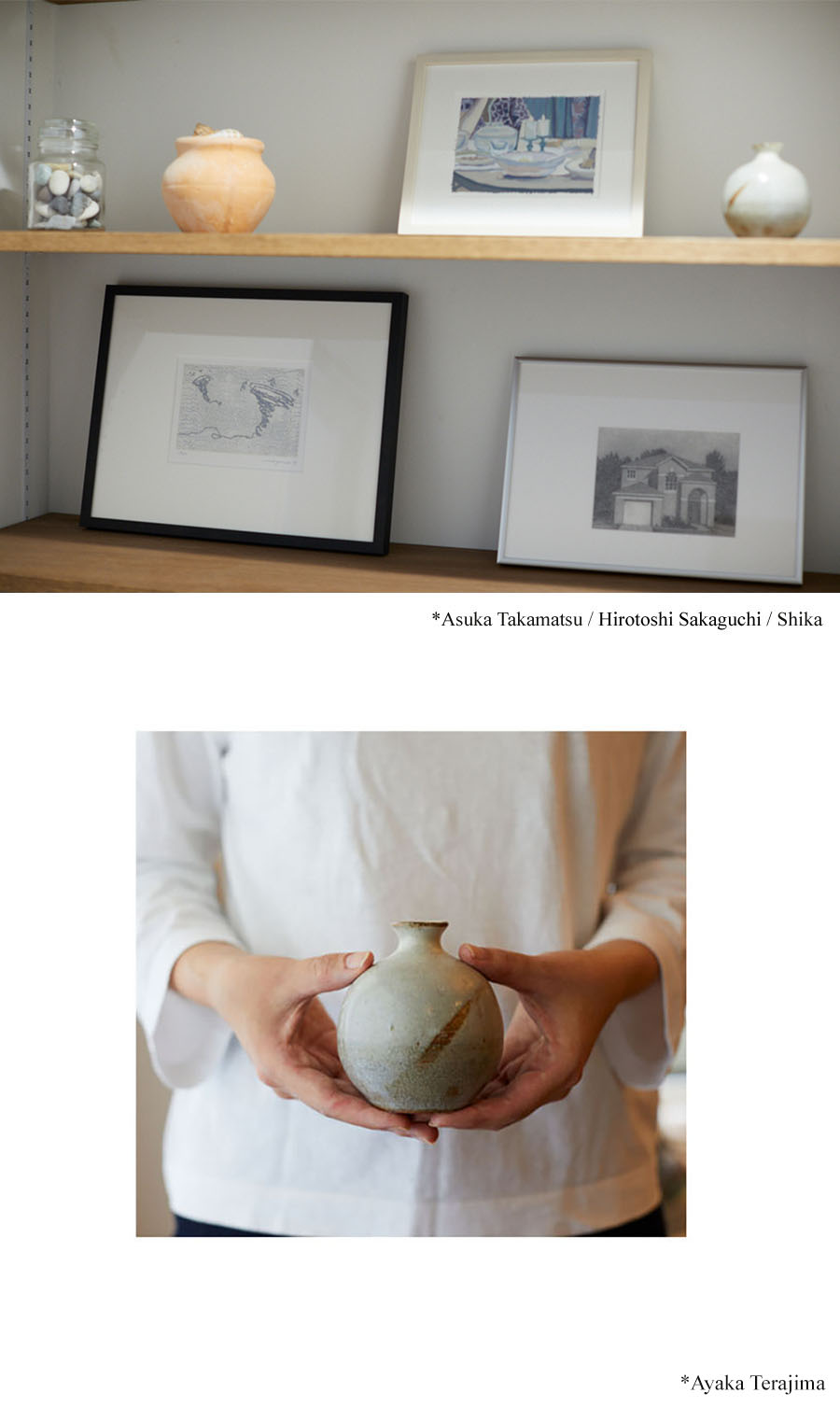

We missed seeing three works that are in the entrance hall on some shelves, almost empty. On one side, some stacked frames that someone gave her and haven’t found their destination yet, and on the other, different pairs of black shoes and beige slippers. Everything in perfect order and harmony of colors.

D. “Tell me a little about this banquet”.

Y. “It’s by Asuka Takamatsu (1984)23an artist who takes scenes from different movies. She paints with acrylic, always in this same palette, of blues, grays, violets. Before I had it in the living room because it is the scene of a meal, but after the renovation of the apartment I put it in this sector.”

D. “I really like her work. And this house painting next to it?”

Y. “A friend gave it to me for my wedding. It is a house that seems uninhabited, right? It’s Shika's24 work."

We turn it over to see the label and the technique of the work, and we discover that it is already about twelve years old. I love the knotted cord used to hang pictures in Japan. The swirling line of the third entry hall work sparks a bit of debate about what it represents. It is the work of a former university professor, her sensei, as it is said here.

Y. “His name is Hirotoshi Sakaguchi (1949-)25. When he retired he made a book of his works that included some prints. I took this and framed it.”

D. “It catches my attention that in Japan there are many galleries where only ceramic objects are exhibited and sold,” I say pointing to a small vase that is next to the three works, and then we decide to include it.

Y. “The potter who made it is called Ayaka Terajima (1987)26.

D. “Let’s take some photos with the object in your hands.”

Y. “I also have this bowl that is from my daughter’s collection, I bought it in Singapore. There is also this jar with stones that I collected when I was a girl.”

D. “Are they from Japan?”

Y. “Yes, they are from Hokkaido island.”

After seeing almost every corner of the house, we sat down at the table to chat a bit and eat some cookies that I brought as a gift. They are not traditional Japanese sweets, I bought them at the Tokyo branch of the iconic Dean & DeLuca American store, but they are inspired by the great hits of the Japanese universe: sakura blossom, Fuji-san and pine tree. Yuna brings an irregular brown ceramic plate that she specially chooses and places the cookies on it. While we take the mandatory photo, the artist shows us the different light intensities that she can operate from her smartphone after renovating her house. There is a certain light that you use to paint, for example, there are other options that are warmer, more intense, or some that are subdued as well.

Y. "Kawaii!” she exclaims in a girlish voice when we’re done.

D. "Kawaii is a word that you use a lot, right?”

Y. “Yes, ha ha.”

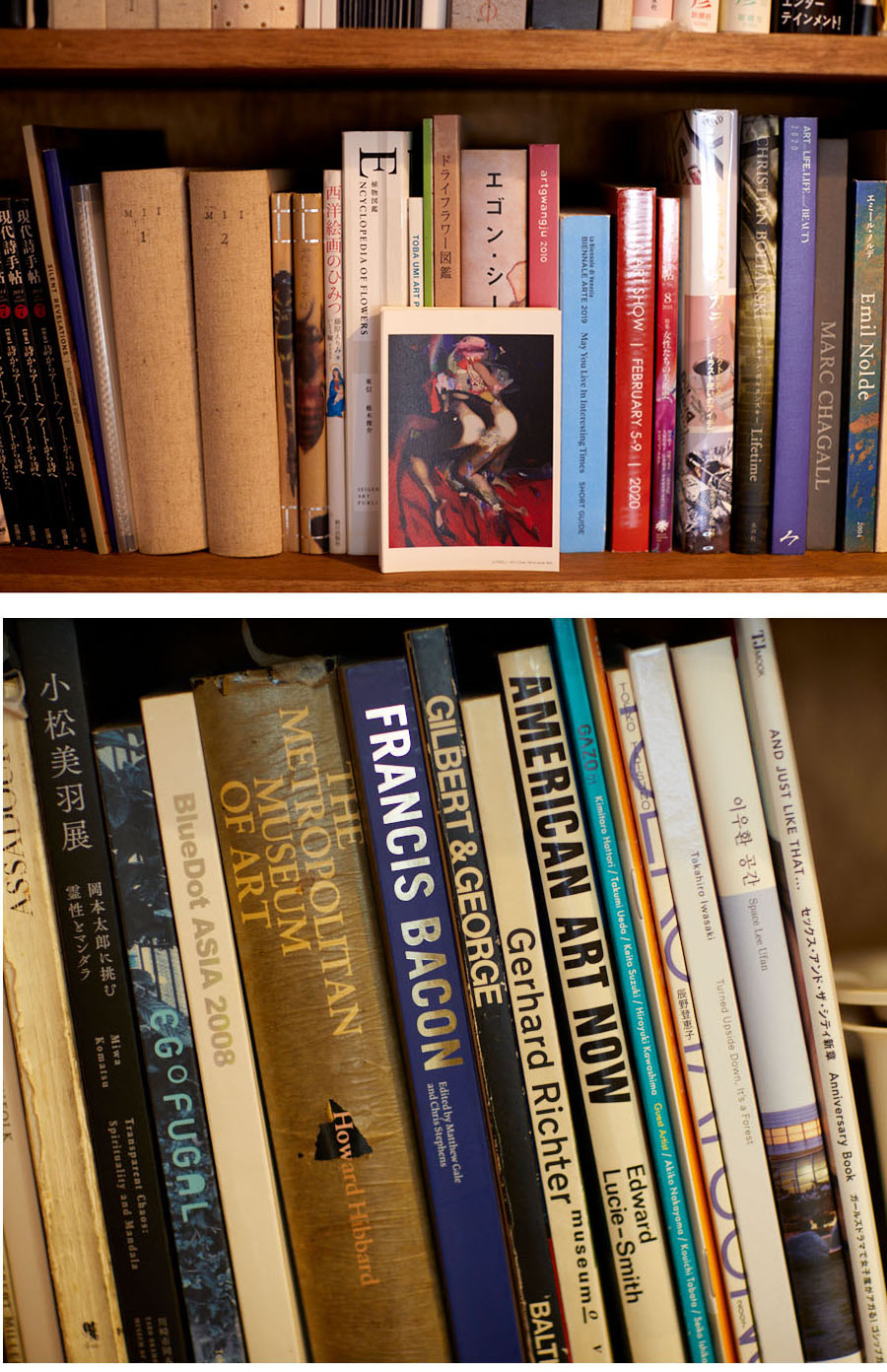

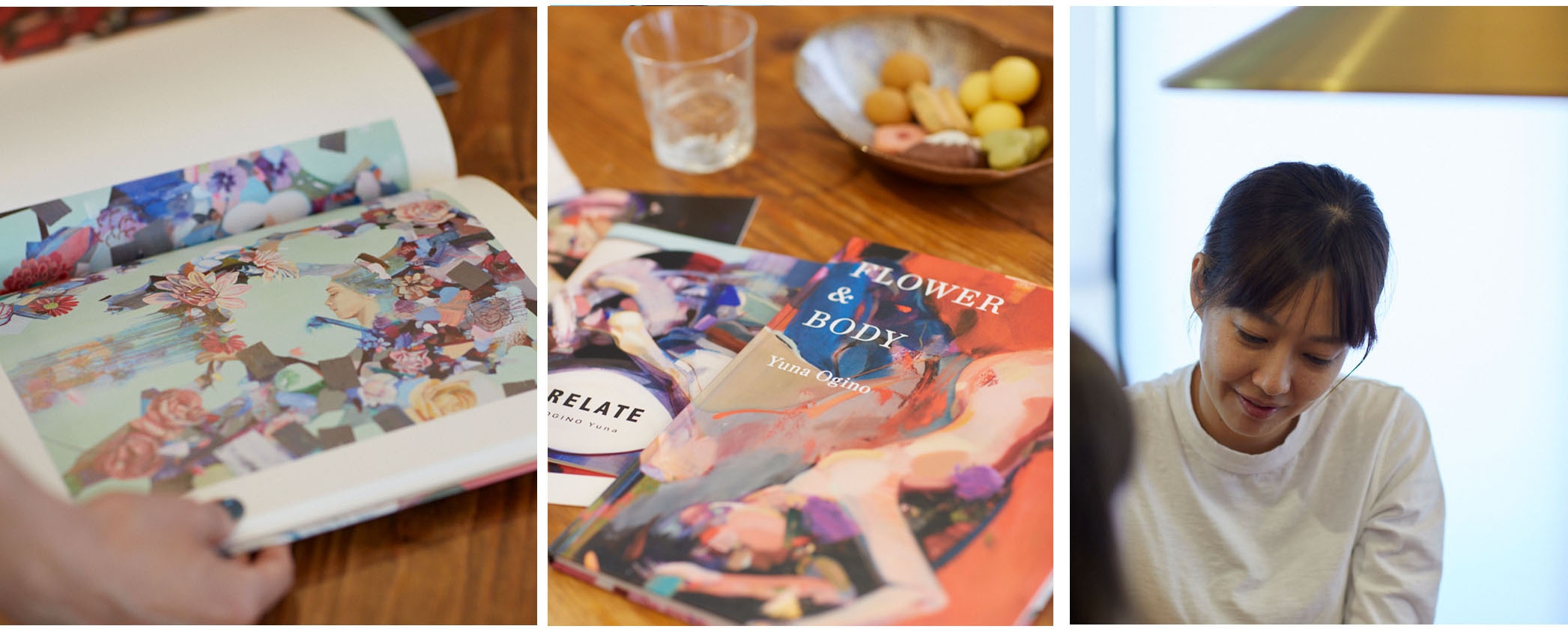

While looking at Yuna’s painting book they tell me about an art event that will take place in the next few days, the Roppongi Art Night27 in Roppongi neighborhood, where several commercial and cultural facilities are concentrated. Headlining this year's festival is contemporary art megastar Takashi Murakami (1962)28, and the theme is 'Magical Adventure' accompanied by the character Doraemon.

D. “Did you edit this book by yourself?”

Y. “Yes, I had the support of a fund, too,” she says while looking for the information on her cell phone, and a few seconds later the recording of a woman’s voice (like an answering machine) is heard saying: ‘Japanese agency for cultural affairs’.” Laughs.

D. “I like this work a lot, it’s very big, isn’t it?”

Y. “Yes, huge. It’s about women’s liberation.”

D. “Do you teach painting at the university?”

Y. “I used to, but about ten years ago.”

D. “And why did you leave?”

Y. “Well, it was a three-year contract, ha ha. Now I give classes privately for adults, children, and people with some type of disability in a place near my house, here in the neighborhood.”

D. “I read in an interview that your father was an art teacher.”

Y. “Yes, he was an art teacher at high school.”

D. “I also read that you started painting at the age of 6.”

Y. “It’s true, yes. I didn’t know that interview was in English.”

D. “Maybe it isn’t, but Google translates it for me, ha ha. I was interested in asking this because, in the book Artists’ Collections, Laura Ojeda Bär tells that she comes from a family of writers and intellectuals and at one point she adds: ‘I grew up in a house where there was nothing hanging on the walls.’ So, I was wondering what images you would have at home with a father who was an art teacher.”

Y. “There was no art hanging on the walls, but there were many artistic materials, he always drew, painted. There was nothing on the walls of my house, just a clock.”

D. “I heard that in Japanese houses there is only a calendar and a clock hanging on the walls.”

Y. “Yes, yes, yes, the calendar, ha ha.”

D. “Yesterday I went to Ueno Park because I wanted to see the university you went to, the Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai)29. Very impressive! Since they obviously don’t let you in, I was looking at their website, and an institutional video of the former director playing the violin caught my attention. I loved when he says that he became interested in the instrument when he was 3 or 4 years old because his mother read him the story ‘The Three Little Pigs.’ Was it difficult for you to study there?”

Y. “Yes, entry is very difficult. Only one in forty applicants enters. I had to prepare a lot, it was not something easy or natural.”

D. “Seeing the courses offered by the university and the orientations that can be chosen, I wondered, why did you choose oil painting instead of, for example, Nihonga, traditional Japanese painting?”30

Y. “I like traditional Japanese painting, but what I don’t like is the work process involved, you have to stay with what you did, you can’t change it. In oil painting, on the other hand, you can change what you are doing, and for what I wanted to do, I needed that.”

D. “Do you think Nihonga is something from the past?”

Y. “I don’t think it’s something from the past, there are a lot of contemporary artists who work with these techniques.”

D. “I was wondering who chose that orientation and I saw that among the famous graduates of the university is Takashi Murakami, and that he studied traditional painting.”

Y. “The Nihonga community is quite traditional, and I didn’t want to be part of that either. But there are some contemporary artists coming out of that conservative circle who are working in the field. But, for example, Murakami’s teachers no longer consider him a Nihonga painter."

D. “Do you like his work?”

She smiles and her gestures show that she doesn’t.

Y. “I don’t like his work, but I do like the way he thinks.”

D. “In some interviews you mention that your work is inspired by the practice of ikebana and Japanese gardens. Tell me more about that.”

Y. “Initially I painted contained flowers, wedding bouquets, putting together a beautiful composition. But then I began to question some things that have to do with women’s freedom and those bouquets began to fall apart. Over time I realized that they no longer have to be perfect, controlled, organized.”

Ikebana or kadō means "path of flowers" and, like the rest of the dō arts, it is a long path of fulfillment, introspection and self-knowledge. We can find its roots in the ceremonial practices of the native Shinto religion and later in the tradition of flower offerings of Buddhism. Let’s think then that these first flower arrangements were made by priests, but around the fifteenth century, the practice of ikebana became secularized. Japanese house design in this period reflects this transition. New houses were built with a special niche called a tokonoma, the aesthetic altar that contains a rolled scroll and flower arrangement and his choice revealed the style of the inhabitant of that house.

In 1927, Sōfū Teshigahara (1900–1979)31the eldest son of an Ikebana sensei, deviates from the tradition he had learned as a child and founded the Sōgetsu school32, taking the practice to the level of sculpture. Since the 1950s his works have been exhibited in museums and galleries inside and outside Japan.

D. “When I was researching ikebana, I came across an exhibition by the French artist Camille Henrot at the Kamel Mennour gallery called Is it possible to be a revolutionary and like flowers? (2012).33

Y. “Oh wow, I’m going to write it down.”

D. “For this exhibition she worked for two years turning each book of her library into an ikebana arrangement. I mention it because, in the West at least, we can imagine that this is a practice of the past, but there are many interesting artists working on the edge of that tradition. I find the works of the master Yukio Nakagawa (1918-)34 disconcerting and his photographs of carnations dripping with blood are exhibited, for example, at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris.”

>> “When I saw this painting of yours with a woman floating surrounded by flowers, it reminded me of Ophelia, the character from William Shakespeare,” I say, pointing to another page from her book.

Y. “Yes, it was the intention, although I don’t receive that feedback so much here in Japan; perhaps it has to do with our artistic education, which, as you say, is different between East and West. But I also think that it doesn’t necessarily have to be Ophelia. What I was looking for was to create an image of a woman who did not fall into the stereotypes and categories of ‘fragile,’ ‘delicate,’ who needs to be ‘protected.’ The same thing happens with flowers, people tend to associate them with the feminine, beautiful, fragile, but I try to change that image and make women strong.”

D. “You also worked with textile designers, fashion designers, right? How was that experience?”

Y. “I have always worked in the art scene, so working with people from other fields seems interesting and inspiring to me. The art world and the art market in Japan are very small, so working in other fields opens more doors and you reach more people.”

D. “Do you think that artists in Japan can make a living from their work?”

Y. “Until three years ago I couldn’t live only from the sale of works, but in the last three years I began to sell more, probably due to Instagram. I also started painting more of the human figure, and that attracted more male buyers. When I made flowers, they were bought mainly by women. The collectors introduced me to other collectors and that’s how I started to sell more and now I can live from selling.”

D. “It must also have to do with the fact that you are working with a very important gallery such as the famous Mizuma Art Gallery”35

Y. “Yes, we’ve known each other for a few years, but it’s only been three years since I joined the gallery.”

D. “That must also have something to do with it, right?”

Y. “Yes, the gallery has given me a lot of opportunities to exhibit, and I think they have had a great influence on my artwork over time.”

D. “I see on Instagram that every time you finish a work, you publish it.”

Y. “Yes. The gallery knows it too. Now that I work with the gallery I can focus more on my work, and they take care of sales and operations.”

D. “You work in a space called Art Factory Jonanjima36, tell me a little about that place. I saw that there are more than thirty artists and designers working there. I wonder if they are like a community or if each one does their job and goes home.”

Y. “There are friends among those who work there, I am more of those who go to work, keep a schedule and return home, ha ha. I joined the place recently, but I know that before the pandemic there were more meetings, barbecues, but I didn’t experience it because I joined later.”

D. “I understand that the project is linked to a hotel called Toyoco Inn Co., Ltd. Is this type of relationship common in Japan?”

Y. “The company had this huge warehouse building, and they had the idea of making this space for the artists to work.”

D. “And do they pay rent?”

Y. “Yes, but it´s affordable for artists. There are workshops of different sizes, with different prices.”

D. “In Argentina there are some spaces that provide workshops to artists and they pay with work. Once a year they give the owner a work, for example.”

What I am saying seems the strangest thing in the world to them. They never heard it, and their eyes open wide.

Y. “I prefer to pay with money and not work to pay the rent.”

When we finish the interview, Yuna offers to take me to visit her studio. Half an hour later by car, and closer to the Haneda airport, we arrive at the Art Factory in the Jonanjima area. A receptionist looks me up on the guest list and gives me a visitor’s badge.

D. “How many times a week do you come here?”

Y. “I come from Monday to Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., I do ‘office hours,’ let’s say.”

The remodeled building, which previously functioned as a warehouse, is located in an industrial area lined with storehouses. In addition to workshops of different sizes for artists and areas for common use, it has several huge spaces for free-admission exhibitions. I am surprised by a permanent exhibition of a very famous Japanese artist, Kimiyo Mishima3790 years old. It brings together a rather impressive set of installations and works carried out between 1984 and 2014.

There are very few artists in the place that day, everything is perfectly ordered and there is absolute silence. We visit Yuna’s workspace, where there are some large canvases in progress that would not fit in her home. The same three-tier cart with wheels that we found in her living room has its double here surrounded by tripods, lights, and paint supplies.

I notice that many artists leave their business cards, something essential in Japan, at the door of each studio. We come across the artist Manami Hayasaki (1980)38 who is working in a nearby studio and kindly improvises a studio visit for us. We walk through the place with Yuna until we reach the terrace, where we take a selfie while we watch the planes go by. It’s already 5:00 p.m. and it’s time to go home. Yuna drives me to a train station that takes me back to the central area of Tokyo along with thousands of workers, who also travel in absolute silence.

Interview: Daniela Varone

Photographs: Marisa Shimamoto

FOOTNOTES

1Marisa Shimamoto: https://www.marisashimamoto.com/

2Yuna Ogino: https://www.yuna-ogino.com and @yuna_ogino_

3Jun Yonekawa: @mondunique

4January: it is tradition to place a pine tree on each side of the front door of houses during the New Year’s Eve. Pine leaves are perennial, resistant to heat and cold, and remain green during all four seasons. As it is also very long-lived, the meaning of “immutable prosperity forever” is attributed to it. For this reason, the pine tree is chosen for the month of January.

5The tokonoma is an essential space of a tatami room, a separate area in one corner of the room, set aside as a miniature art space. With the subtle changes of the seasons, the decorations of the tokonoma also change. Hanging scrolls display a painting or a famous calligrapher's rendition of a traditional, seasonally appropriate poem. An ikebana arrangement captures in miniature a landscape with flowers and plants of that season, often the same landscape, which is the subject of the painting or poem on the hanging scroll. Other decorations may include a treasured antique or a framed painting that rests on the floor of the tokonoma.

6Sakura blossom: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/03/23/national/cherry-blossom-forecasting/

7Julían Varsavsky, Japón desde una cápsula. Adriana Hidalgo editora, 2019.

8Masayuki Oku: https://www.okuart.com/

9Hidemi Takaku: https://suiran8art.base.ec/

10Arisa Odawara: @arisaodawara

11Yoshitomo Nara: https://www.yoshitomonara.org/en/

12 Yoshitomo Nara prices at auctions: https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-yoshitomo-nara/record-prices/yoshitomo-nara-record-prices

13N´s Yard: https://www.nsyard.com/en/about/

14N´s Yard Garden: The garden retains the area's native trees alongside seasonal plants. In spring, visitors can enjoy various flowering plants, including three varieties of sakura. Summer brings wonderful greenery, along with flowers such as the Japanese spiraea and Hydrangea involucrate. Golden-rayed lilies grow wild around July - August, while September - October brings the flowers and scent of the fragrant olive. From autumn to winter, visitors can view the red and yellow leaves of several Japanese maple varieties”. https://www.nsyard.com/en/about/yard/

15Jenny Saville: https://gagosian.com/artists/jenny-saville/

16Sumiko Iwaoka: on her www.sumikoiwaoka.com she wrote: “In my recent works, my interest has turned to the world that becomes visible when you superimpose the universal beauty of masterpieces with the daily life that passes by.”

17Book: Ukiyo, Yoshitomo Nara. Publicado por Masaku Takei (Little More), 1999.

18Chu Asai: https://www.artizon.museum/en/collection/category/detail/252

1921_21 Design Sight is a museum dedicated to design, founded in 2007 by architect Tadao Ando (1941–) and designer Issey Miyake (1938–2022) It is located in an area called Tokyo Midtown, that was created to be the center of design culture in Japan, driven by facilities including 21_21 Design Sight, Suntory Museum of Art, and Tokyo Midtown Design Hub. Tokyo Midtown is home to the National Art Center, Tokyo, the Mori Art Museum, the design-themed complex AXIS, TOTO GALLERY•MA, and a number of design offices.www.2121designsight.jp.

20Nihonga paintings are done on washi (Japanese paper) or silk. Initially they were produced to hang on rolls that were moved by hand or on screens. In the case of monochrome paintings, sumi (Chinese ink) is used, based on soot mixed with a fishbone glue. In polychrome paintings, the pigments are obtained from natural ingredients: minerals, shells, corals, and some semi-precious stones (malachite, azurite, and cinnabar). For these powdered pigments, a hide glue solution, called nikawa, is used as a binding agent.

21Chihiro Ogawa: www.ogawachihiro.com

22Sato Sugamoto: www.sato-sugamoto.com

23Asuka Takamatsu: http://takamatsu-works.blogspot.com/

24Shika: www.shikartworks.com

25Hirotoshi Sakaguchi: https://www.gallery-58.com/exhibition/2022_exhibitions/2022_sakaguchi/

26Ayaka Terajima: https://ayakaterajima.myportfolio.com/work

27Roppongi Art Night: https://www.roppongiartnight.com/2022/en/

28Takashi Murakami: https://gagosian.com/artists/takashi-murakami/

29Tokyo University of the Arts: https://www.geidai.ac.jp/english/

30 Yōga and Nihonga Paintings: In 1876, the Meiji government created the Kobu Bijutsu Gakko (Technical School of Fine Arts), Japan's first art school dedicated to Yōga—the style of painting by Japanese artists done in accordance with Western (European) conventions, techniques, and materials. To carry out this mission, they hired some Italian artists as teachers, among them Antonio Fontanesi (1818-1882). However this school lasted less than a decade.

In the 1880s, the general reaction against Westernization and the growth of the Nihonga movement (Kakuzō Okakura (1862-1913) and Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908) are two standard-bearers in this cause) caused the temporary fall of Yōga. The school had to close its doors in 1883, and when the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko (precursor of the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music or Geidai) was created in 1887, the Western painting department no longer figured on its curriculum. The following year, Kakuzō Okakura was appointed director. Okakura was a member of the Imperial Art Commission sent by the government to investigate art in Europe and the United States, but instead of being fascinated by foreign productions, he had an intense appreciation for Asian and Japanese art.

But the encounter was not going to end there, and in 1889 Yōga artists created the Bijutsukai Meiji (Meiji Fine Arts Society) and in 1893, the return of the painter and teacher Seiki Kuroda (1866-1924), considered the father of Yōga, from his studies in Europe gave a new impetus to the genre.

When it became clear that European methods were to become increasingly important in the school's curriculum, Okakura resigned his position and in return founded the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Academy of Visual Arts), along with 39 other artists, where they spread their aesthetic nationalism.

Since 1896, a Yōga department is part of the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko study department, Seiki Kuroda was invited to be its director, and henceforth Yōga became an accepted part of Japanese painting.

31Sōfū Teshigahara: https://www.takaishiigallery.com/en/archives/26602/

32 Sōgetsu: https://www.sogetsu.or.jp/e/works/

33Camille Henrot: https://mennour.com/exhibitions/is-it-possible-to-be-a-revolutionary-and-like-flowers

34Yukio Nakagawa: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-585-2003-01-19.html

35Mizuma Art Gallery: https://mizuma-art.co.jp/en/

36Art Factory Jonanjima: https://www.artfactory-j.com/

37Kimiyo Mishima: https://mem-inc.jp/artists_e/mishima_e/ and a video of the show: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIVOFgP4vCg

38Manami Hayasaki: www.manamihayasaki.com